The 1960s - Haiku Learning

advertisement

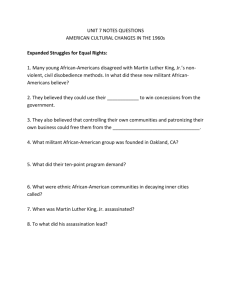

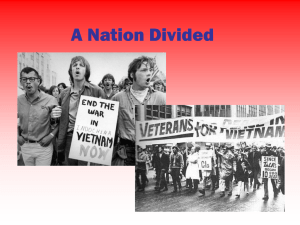

The 1960s In A Nutshell The sixties: it wasn't just "The Age of Aquarius," it was truly an age of reform and revolution. Mainstream politicians launched a multifaceted campaign to eliminate poverty, expand government services to the elderly, and increase educational opportunities for people of all ages. Over the course of the decade, Congress passed historic legislation transforming the role of government in American society. The Civil Rights Acts of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Medicare, Medicaid, Head Start, the Job Corps, the Office of Economic Opportunity, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and the Department of Transportation were all part of this legislative record. But reform was not confined to the Washington political establishment. Student activists rallied to fight racial segregation and end the Vietnam War. Much of this protest was peaceful; students cited the examples set by Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. in seeking nonviolent social change. But some activists lost confidence in nonviolent methods as the decade passed and the war in Vietnam continued. Radical factions like the Weathermen argued that the war abroad and racial and class injustices at home required more aggressive responses. By the end of the decade, these militants had gone underground to wage a campaign of targeted bombings against government institutions linked to the war and “oppression.” Other reformers and revolutionaries eschewed politics for cultural and social change. These prophets of the counterculture sought to transform the ways Americans worked, lived, and loved. They denounced materialism and capitalism; they encouraged selfexploration and self-fulfillment and offered wide-ranging prescriptions toward these ends—drug use, sexual experimentation, communal living, and non-western religions. At the same time, popular stereotypes notwithstanding, the sixties was not a decade that belonged entirely to the counterculture and to left/liberal political movements. The modern conservative movement that later came to dominate American politics through the Reagan and Bush Eras was born in (and of) the 1960s as well. Why Should I Care? The 1960s was a decade of slogans. Students chanted “Stop the War.” “Hippies” extended an invitation to “turn on, tune in, and drop out.” John Kennedy urged Americans to explore a “New Frontier,” and Lyndon Johnson pledged to build a “Great Society.” It’s easy to list the catchy phrases coined by protestors and politicians. It's harder to recreate the vision and sense of opportunity that inspired these slogans. During the 1960s, people of all ages and backgrounds became convinced that America could build a new society—a nation in which no one was poor or exploited, everyone could be educated, and the sins of America’s past, like racism, would be redressed. Not everyone nursed the same vision; some pushed their critique of contemporary society further than others. And, somewhat ironically, people who shared common goals on some issues found themselves violently at odds over other social questions. Still, there is something striking in the fact that a New England blueblood and a hard-nosed Texan, thousands of idealistic college students, and just as many young countercultural revolutionaries would share the same basic belief that America was on the edge of a new, more perfect time in history. So, what exactly brought them together—and what drove them apart? Why the 1960s—why not sooner or later? And what did all this idealism and vision produce? Summary & Analysis: During the 1960s, students across America rose up to demand reform. On campuses from Berkeley to New York, they demanded desegregation, unrestricted free speech, and withdrawal from the war in Vietnam. Highly idealistic and inspired by periodic successes, the students believed they were creating a new America. During the 1960s, young Americans on and off campuses challenged conventional lifestyles and institutions. They protested the materialism, consumerism, and mania for success that drove American society. They urged people to explore alternative patterns of work and domesticity. They challenged traditions surrounding sex and marriage. And they argued that all paths to deeper fulfillment, even those involving illicit drugs, could be justified. They believed they were creating a new America. In 1961, John Kennedy coupled his presidential oath of office with an announcement that the torch of American idealism had been passed to a new generation. He called on Americans to join in a self-sacrificial campaign to explore a new frontier. Together they would fight “tyranny, poverty, disease, and war itself.”12 They would send American ambassadors of good will around the world, and they would even land a man on the moon. Kennedy called on Americans to create a new America. In 1963, Lyndon Johnson assumed the presidency and immediately set about expanding Kennedy’s vision of social and economic perfection. He vowed to win the war against poverty and build a “Great Society” that elevated the poor, cared for the elderly, and offered educational opportunities to all. Johnson would push through Congress one of the most ambitious and extensive legislative agendas in history. Medicare, Medicaid, VISTA, Head Start, federal college scholarships, and the Office of Economic Opportunity all were created under his leadership. Johnson, the United States Congress, and the 43 million people (61% of the voters) that gave Johnson an enormous mandate in 1964 believed that they were creating a new America. We tend to equate the idealism of the 1960s with the student movements and the counterculture that offered the most dramatic challenges to American policies and conventions. But the truth is, idealism crossed generations and permeated almost all levels of public life. Perhaps no period in American history has been filled with such an expansive and ambitious sense of possibilities— such a grand, inspiring sense of what Americans could achieve. Of course, not every American marched in lockstep to the same vision of “progress.” In many places, north and south, segregation was defended. Citizens and politicians questioned the wisdom of expanding government services, arguing that they were costly and might breed a culture of governmental dependency. The new lifestyles advocated and lived by members of the counterculture were condemned as immoral and anarchistic. Student protestors were labeled self-indulgent children without the experience to make sober judgments. And not every reform or vision advanced during the 1960s survived into the 1970s. American capitalism did not collapse under the pressure of student revolutionaries. Consumerism remained an essential element of American society. And many of the conventional institutions and practices of both Wall Street and Main Street persisted. But student protestors did contribute to the end of the war in Vietnam, they did advance civil rights, and they did transform the culture of American colleges. Many of the values of the counterculture did work their way into the mainstream. America’s workplace is now more diverse and flexible, our sexual ethics have changed, and environmentalism has become a widely embraced set of values. Many of the programs created under Kennedy and Johnson are now accepted fixtures within the nation’s web of social services. Poverty has been reduced, America’s elderly are better cared for, and educational opportunities are far greater. And in 1969, the United States landed a man on the moon. The 1960s remain a controversial decade. Critics argue that the era created the welfare state, bred a culture of immorality and self-indulgence, and bequeathed to America’s taxpayers an enormous burden. Its defenders, on the other hand, argue that the decade left America’s political and social institutions more just, and its culture more healthy. The 1960s did create a new America. The question is, was “new” better?