The Benefits of the Introduction of Deep Brain Stimulation to Ireland

advertisement

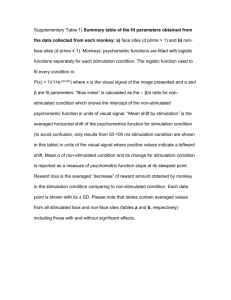

Submission to the Joint Committee on Health and Children On The Benefits of the Introduction of Deep Brain Stimulation to Ireland Dr. Richard Walsh MB, MD, MRCPI Consultant Neurologist Tallaght Movement Disorders Unit Adelaide and Meath Hospital Dublin Incorporating the National Children’s Hospital Professor Timothy Lynch MB, BSc., DCH, FRCPI, FRCP, ABPN Consultant Neurologist Mater Misericordiae Hospital Dublin Neurological Institute Mr Gavin Quigley MBChB, FRCS(Neurosurgery) Consultant Neurosurgeon Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast. Thursday 6th November 2014 1.0 Background 1.1 Parkinson’s disease Parkinson’s disease is one of a family of disorders known as neurodegenerative disorders. These are disorders that typically arise in adult life and result from a slow and progressive loss of brain cells at a rate that is faster than expected in normal ageing, disrupting the neural circuits that drive movement, cognition and emotions. The specific features of each disease depend on which population of cells are lost. Frustratingly, for physicians and patients alike, we have yet to identify an effective way of protecting these neurons from premature loss in any of these degenerative disorders and management is therefore centred on symptom control. Parkinson’s disease is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder in Ireland after Alzheimer’s disease. The disease affects almost all aspects of daily living, although much of the disability in Parkinson’s disease relates to the loss of cells that produce dopamine, a critical messenger in the brain that facilitates normal movement. The loss of these cells leads to stiffness, slowness, tremor and balance difficulty that becomes more prominent over time. There was a revolution in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease in the 1960s with the discovery of levodopa as a treatment that could be delivered orally in tablet form. This drug is converted into the lost messenger dopamine. The use of this drug was nothing short of miraculous in the way it transformed disability into normal movement and therefore return normal function or close to normal function for people with Parkinson’s disease. For some people with Parkinson’s disease the striking benefit of levodopa treatment diminishes in quality and quantity over time. Although the drug’s efficacy is never lost, the brain’s ability to utilise it over time becomes erratic, unreliable and unpredictable. People who enter this phase of their illness in which they have socalled ‘motor complications’ experience dramatic changes in their ability to move from hour to hour. Pills have to be taken with increasing frequency and often provide progressively diminishing periods of normal movement. These brief periods of relative normality can be further contaminated by excessive involuntary writhing movements known as dyskinesia, representing the other extreme of a roller coaster of movement. The cost of Parkinson’s disease at this advanced stage increases significantly, both directly due to drug costs and indirectly due to lost productivity, reduced working time for carers and longer hospital stays (Findley, 2011). 1.2 Deep brain stimulation and Parkinson’s disease Over the last 20 years, patients with disabling motor complications of their Parkinson’s disease have experienced a second therapeutic revolution in the form of deep brain stimulation. Deep brain stimulation involves the placement of electrodes into specific parts of the brain by a team of neurosurgeons specifically trained in functional neurosurgery. Unlike most forms of neurosurgery, which involve removing abnormal brain tissue, functional neurosurgery aims to modulate brain activity, using carefully targeted electrical impulses to restore function. Deep brain stimulation thus allows us to fine tune abnormal circuits in the brain that misbehave as part of a disease process such as Parkinson’s disease. Stimulation is delivered via a ‘pacemaker’ battery placed under the skin that must be replaced intermittently. This battery can be fine tuned according to the patient’s needs by a team of doctors in the programming stage post-operatively. The critical difference between deep brain stimulation and the standard oral medications we use in Parkinson’s disease is the fact that the benefit stimulation provides is continuous throughout a 24-hour period, reliable from day to day, and maintained in the long term. From an individual perspective, deep brain stimulation can be transformative, returning to a patient hours of their day that previously were characterised by disability and dependence on a carer. Many trials of deep brain stimulation versus best medical therapy have shown the superiority of surgery over best medical therapy for the small proportion of patients that meet criteria for surgery in Parkinson’s disease (Hilarion, 2014). The wider benefits in terms on general well being, restoration of normal relationships, a return to the workforce, reduced hospital attendances and societal integration are less well measured but perhaps more significant. There are available alternatives to deep brain stimulation for people with Parkinson’s disease who experience disabling fluctuations in their movement. Pump therapies can deliver drugs under the skin (apomorphine) or through a tube passed into the small bowel (levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel). This continuous pumpbased delivery can relieve the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease in a more reliable way than tablets taken intermittently can. These pump therapies have been used successfully in many patients for a number of years and have an important place in the war-chest we have at our disposal to restore movement in Parkinson’s disease. Importantly, neither of these pump options can match the efficacy of deep brain stimulation when indirectly comparing the data available. Furthermore, and of greater importance from a societal point of view is the greater cost of these pump therapies which carry a recurring year-on-year cost. Deep brain stimulation is associated with a 50-60% reduction in medication requirements. After two years the cost of the surgical episode and hardware are covered by this medication saving, making it cost effective with respect to the alternatives (Valdeoriola, 2013). Although economics does not come into individual choices of best therapy for a given patient, this is an important consideration when planning for the future therapeutic landscape for this increasingly common disease in our aging population (Dams, 2013). 2.0 Other Conditions treatable by Deep Brain Stimulation 2.1 Essential tremor Essential tremor is a common movement disorder characterised by disabling upper limb tremor when an affected person attempts to use their arms in performing any task. Prevalence statistics vary widely but conservatively it is estimated that 1% of the population are affected and this rises to over 5% amongst people over 65 years. The resulting tremor can be mild or moderate and many people continue to work and do not seek medical attention. For some people the tremor is severe and incapacitating making the most simple of tasks impossible such as drinking from a cup or glass, signing a cheque, doing up buttons or shaving. Medical options for the treatment of essential tremor are very limited and often unsuccessful at best. Deep brain stimulation, however, can abolish essential tremor and restore function where it has been lost (Baizabal-Carvallo, 2014). 2.2 Dystonia Dystonia is a less common movement disorder than Parkinson’s disease or essential tremor but still may affect as many as 3000 people in Ireland. This condition is characterised by sustained abnormal postures and twisting movements of the neck and limbs produced by muscles contracting in an involuntary way. Dystonia can be localised to a single body part or can be generalised where it is at its most disabling, affecting the entire body which can make sitting or lying down difficult. Dystonia is often painful and secondary problems with joint development and breathing are seen in affected children who develop skeletal malformations as a result of sustained muscle spasms. We unfortunately have no useful medicines for the treatment of dystonia. Injections of botulinum toxin can reduce spasms but are impractical where many muscles are involved and sometimes ineffective. Deep brain stimulation can provide significant long-lasting (Fitzgerald, 2014; Walsh, 2013) improvements in focal and generalised dystonia by restoring normal neural function capable of returning lost ability to walk, feed and perform self-care in affected patients. 3.0 Current Service Provision of Deep Brain Stimulation 3.1 The patient experience As things currently stand, deep brain stimulation is not available in the Republic of Ireland and this is unusual by international standards in comparison to other developed nations of our size. Our two neurosurgical centres in Dublin and Cork are not currently resourced to offer deep brain stimulation for any of its indications and at this point in time we do not have neurosurgeons with training or experience in its provision. People with Parkinson’s disease must therefore be referred to centres in the United Kingdom, and sometimes beyond, for assessment and surgery under the Treatment Abroad Scheme. The complex decision making process that brings physician and patient to the point of weighing up the risks and benefits of brain surgery therefore marks only the start of a long and stressful process involving multiple flights abroad for assessments, surgery and then programming. Notably, for the patients who undertake this process, movement is so difficult that the potential risks of brain surgery are outweighed by their desire for treatment success. Negotiation of transport to one of our airports, travel and overnight stays abroad with return trips if accepted are difficult, fraught with stress and anxiety and without any comparator in medicine in Ireland that we aware of. In addition, the cost of travel for the surgical candidate, one or two carers and hotel accommodation must be added to the total cost of surgery abroad. 3.2 The treating neurologist’s experience As neurologists treating patients who have travelled to the United Kingdom for deep brain stimulation, the practicalities of management following surgery can be challenging. Although our colleagues abroad are leaders in their field and provide an excellent service to our patients, the geographical and therapeutic disconnection can be frustrating and even dangerous at times when complications occur. We do not have ease of access to operative targeting information or imaging, we do not have access to data relating to the post-operative programming and we have no MRI department that is equipped to scan these patients should they require one for any reason due to their metal implants. Furthermore, and possibly of greater therapeutic significance, is the post-operative programme required in a crosschannel approach. The careful and gradual reduction in oral drug therapy while electrical stimulation is increased in the programming stage is optimal if done locally and frequently over 5 to 7 visits taking place every one to two weeks. This is accepted as best practice amongst experts in the field. Irish patients are very well cared for abroad, but the challenges of travel mean a modified programme of monthly programming over half the number of sessions is necessary. Many neurologists in Ireland have had the experience of having a patient with deep brain stimulation who has suffered a hardware malfunctions (e.g. battery failure, lead fractures) or infection. These neurosurgical emergencies must be negotiated via communication with busy neurosurgical centres in the United Kingdom and are further complicated by the need to apply for travel approval for an increasingly unwell and often suddenly disabled patient. 4.0 The benefits of a cross border solution for Ireland There are therefore compelling reasons for the patient and their treating medical team to look for an alternative to the status quo, i.e. the establishment of a neurosurgical centre on this island to treat Parkinson’s disease and related movement disorders. Such a centre will need to be run by a neurosurgical team with access to the appropriate hardware, working in tandem with movement disorders neurologists and adequate nursing support to guide patient selection and post-operative treatment. Aside from the difficulties outlined that mitigate against the retention of the current state of affairs, there are many strong positive factors which additionally support the development of cross-border collaborative deep brain stimulation service: Access is key in healthcare. The accessibility of this service ‘locally’ in Ireland will inevitably give rise to an expansion in numbers of patients opting for this mainstream treatment which is currently viewed by many patients as a curiosity experienced by the few willing and physically able to travel abroad for it. Deep brain stimulation is the most cost effective therapy for patients with motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease. After 2 years the initial investment in hardware and surgical costs are covered by the reduction in medication possible post-operatively. Unfortunately, the up-front cost of establishing a deep brain stimulation service in the Republic of Ireland proved to be prohibitive in economically difficult times at the time of the HIQA Health Technology Assessment in 2012. A cross border collaboration will allow patients in the Republic of Ireland access an internationally recognised facility in Belfast, avoiding this cost but at the same time reaping the economic benefit of DBS in the medium and long term until such a time that a unit in the South can be established. The likely patient demand would support two centres. On this island we now have an internationally trained quorum of neurologists and neurosurgeons who are experts in this field and a total 32 county population of sufficient size to develop one or two centres of excellence for the delivery of a national deep brain stimulation service. This will break our reliance on the financially and logistically inefficient treatment abroad process and will ensure we can deliver local treatment in a safe way that delivers both clinical outcomes and an acceptable patient experience. The additional safety factor and related reassurance for patients and physicians in knowing that a local neurosurgeon familiar with their case is available with same-day access by car, train or ambulance for postoperative complications is critical and invaluable. This is best appreciated by those of us admitting these patients to general hospitals in the Republic while urgently faxing forms and leaving messages in an effort to secure passage to the United Kingdom under current arrangements. In the Republic of Ireland we do not have a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) department which can perform MRI imaging on patients who have had deep brain stimulation. This is for safety reasons, where knowledge of implanted material is limited and where the necessary MRI hardware designed to manage patients with implants in situ is not available. When patients who have had deep brain stimulation present with headache or stroke symptoms, we are limited to performing less detailed and less useful CT scans. This can be a significant diagnostic limitation at times and one that would not exist with a cross-border collaboration allowing access to specialist MRI equipment or indeed if a centre evolves over time in the Republic. The development of local deep brain stimulation expertise in Ireland is essential for the training of future neurologists and neurosurgeons in the rapidly expanding field of functional neurosurgery. There is a very real threat that Irish patients with neurological disease in the future will be left behind in the wake of a field of neuroscience that has grown exponentially in the range of targets and conditions that may be amenable to treatment with deep brain stimulation. We need to put in place the structures to harness this rapid explosion of potential that has spread from the treatment of tremor into surgical approaches for other disorders affecting brain circuitry including drug resistant depression, Alzheimer’s disease and epilepsy. We have the expertise on this island to do this but need the political will and assistance to put the required framework in place. There is enormous potential for academic medical centres on both sides of the border to share data and participate in cutting edge neuroscience research in the area of functional neurosurgery. We have a pool of hugely talented researchers in the fields of neural engineering, neuropsychiatry, neuroimaging and translational neuroscience in this country. Patients we are sending abroad for deep brain stimulation who look to participate in research are unable to provide any data to these researchers and there is therefore a huge loss of research potential. A neurosurgical unit nested within an academic centre on this island working in collaboration with colleagues throughout the island to share preoperative, intra-operative and postoperative data would open an exciting number of avenues in neuroscience research. Summary Deep brain stimulation is now a well-established and evidence based treatment for a number of chronic and disabling neurological conditions. In carefully selected patients, for whom available alternative treatments fail to provide an acceptable quality of life, surgery can provide significant symptomatic benefit. This benefit has been clearly demonstrated using clinical outcome scales. The additional benefits to the individual, society and the healthcare system are substantial in returning patients to work and a productive role within their families and communities. For many people with movement disorders in Ireland, deep brain stimulation in inaccessible and for this reason many good candidates are unnecessarily experiencing day-to-day disability. Ireland is almost unique amongst European nations with a developed healthcare system in not being able to provide this therapeutic option locally. The need to travel imposed on patients, some with severe motor disability, is difficult to justify and warrants consideration of an alternative approach until a surgical service can be established in the Republic of Ireland. We therefore fully support the establishment of Irish deep brain stimulation service with our colleagues in Belfast to deliver the best available treatment to selected patients in a manner that is acceptable to them, their carers and the doctors managing their condition. References: Hilarion et al. Deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.J Neurol 2014 (published online 2 Feb 2014) Findley LJ, Wood E, Roeder C, Bergman A, Schifflers M. The economic burden of advanced Parkinson’s disease: an analysis of a UK patient dataset.’J Med Econ 2011; 14(1): 130-9 Dams J et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Deep Brain Stimulation in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease. Movement Disorders 2013;28(6) Valldeoriola F, Puig-Junoy J, Puig-Peiro R, Workgroup of the SCOPE study. Cost analysis of the treatments for patients with advanced Parkinson's disease: SCOPE study.J Med Econ 2013;16(2):191-201. Epub 2012 Oct 29. Fitzgerald JJ et al. Long-term outcome of deep brain stimulation in generalised dystonia: a series of 60 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014. (published online April 2014) Walsh R.A. et al. Bilateral pallidal stimulation in cervical dystonia: Blinded evidence of benefit beyond 5 years. Brain 2013;136(3):761-769 Baizabal-Carvallo JF, Kagnoff MN, Jimenez-Shahed J et al.The safety and efficacy of thalamic deep brain stimulation in essential tremor: 10 years and beyond. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014 May;85(5):567-72.