Selfhood as Self-Representation Kenneth A. Taylor Stanford

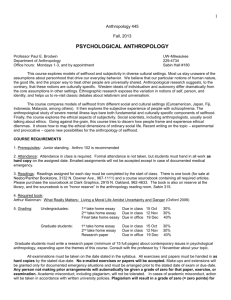

advertisement