Performance-based legitimacy

advertisement

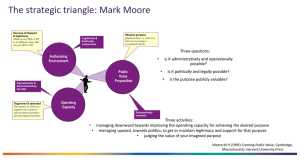

Legitimacy by performance in democratic systems? Preparing for empirical analysis Jon Pierre University of Gothenburg and University of Nordland Asbjørn Røiseland University of Nordland Annelin Gustavsen Nordland Research Institute Paper prepared for Nordisk Kommuneforskerkonferanse 2011, 24-25 November 2011, Gothenburg, Sweden Introduction The paper outlines a framework for an empirical analysis of performance-based legitimacy. In order to prepare the rather fuzzy concept of performance-based legitimacy for empirical analysis we will begin by conducting a conceptual analysis of legitimacy and rehearse the literature in this field. By disentangling the concept of democratic legitimacy we can develop a framework for an understanding of how governments are legitimized not only through procedural democracy and participation, but also through performance, that is, service delivery. Following that, we discuss and elaborate on some basic concepts and variables which we deem likely to have an effect upon performance-based legitimacy. The basic point of departure of the paper is not that governments just recently have come to see that their legitimacy in part is related to policy outputs or outcomes and that social scientists are increasingly directing their attention to this new phenomenon. It is safe to assume that governments at different institutional levels always, to smaller or greater extents, have been considered legitimate primarily because of what they deliver (see, for instance, Gilley 2006). Instead, we depart from the more recent, but now rapidly growing interest in output-based legitimacy as a result of changes in public management and democratic representation. The significance of the input- and output interfaces between the state and the citizenry appears to be gradually changing from an emphasis on representation towards an emphasis on delivery and output, and it is this development which has brought issues related to output-based legitimacy and its relationship to input-based legitimacy to the recent attention of political scientists. In the Eastonian intellectual tradition, legitimacy was primarily related to the input side of the political system (see Crozier, 2010). Even if the model itself emphasizes output and outcomes, the core processes providing legitimacy belong to the input side, ensured by feedback mechanisms from output to input. Empirical research on institutional trust and legitimacy has therefore almost exclusively been embedded in electoral studies research programs which, by default or design, are focused on democratic representation. There was good reason for that; service delivery has historically not offered any choice on behalf of the client. More broadly, the constitutional architecture of the advanced democracies departs from a strong notion that democratic government, and the legitimacy of that government, can only be ensured through a representative process. By electing politicians, empowering them to make ‘authoritative decisions’ (Easton 1965), and holding them to account at future elections government will become both responsive to popular preferences and equipped with some degree of institutional integrity. A number of fairly recent developments within the political system, in society, and in state-society interactions have propelled a reconsideration of the viability and validity of the theory sustaining these constitutional arrangements. The policies of the political parties are believed to be converging; conventional forms of political participation are decreasing (Dalton and Wattenberg 2000); the responsiveness of political parties to voters’ preferences has been called into question (Katz and Mair 1995); accountability through conventional channels is becoming more complex and, at the same time, increasingly misleading (see Peters and Pierre 2011 and the literature cited there); and, perhaps most importantly, while citizens qua voters participate only on election day, citizens qua clients or customers have daily encounters with the state through the public administration and public service delivery and are increasingly empowered to voice their preferences directly with those who deliver those services (Brewer 2007; Pollitt and Bouckaert 2004). Against this backdrop, it is not a very bold assumption to suggest that the sources of political legitimacy of the state are changing as well. The legitimacy of the contemporary state is derived not just from the fact that it is controlled by elected officials but also that citizens receive tangible 1 services and benefits from the state. The more intriguing set of research questions revolve around the relative significance of conventional, procedure-based legitimacy on the one hand and the arguably growing importance of output, result- and performance-based legitimacy on the other. We know that political systems at all institutional levels generate legitimacy from their capacity to provide democratic governance and from the services they deliver (Scharpf 1999; Gilley 2009; Rothstein 2009). Traditionally, the essential sources of support and legitimacy—indeed, the systemic features that make government democratic—are closely related to the input, representative, side of the political system. Thus, the defining characteristics of democratic governance include typical input-related features such as freedom of speech and elective and accountable representative offices. These democratic features of government, in turn, reproduce popular support and legitimacy for the political system (Gilley 2006; 2009). While there has also been some understanding that legitimacy can be linked to distributive features of government as well, we know much less about how important those aspects of the political system are in terms of generating legitimacy. Today, however, a growing number of scholars question several aspects of the conventional way of thinking about the relationships between procedures, performance, democracy, and legitimacy. These scholars argue that public administration and public service delivery, i.e. state-society interactions at the output side of the political system, are becoming as important as a source for democratic legitimacy as input-related factors, if not even more so. This development from procedures to performance is driven by a variety of factors which can be internal or external to the state. We will elaborate on this issue in more detail later in the paper. Performance-based legitimacy – a last resort? Today we observe that the model of representative democracy is challenged by changes in the organizational structure, management models and modus operandi of the public sector. Devolution, outsourcing, fully or limited controlled companies delivering public services and collaborative forms of governance like networks and partnerships displace political control and weaken the linkage between popular preferences and policy output. The linkage between the demos and system output has become more indirect. Elected politicians do no longer necessarily constitute the political centre, as the logic of representative democracy stipulates (Crozier 2010:505). Several observers suggest that such indirect governance, encouraged by the New Public Management reforms implemented over the last decades, even poses a potential ethical threat to the democratic system as such (Dobel 2005; Frederickson 2005:178; Andersson and Bergman 2008). Many of these changes have been well documented. In Scandinavia, the so-called ‘power and democracy studies’ argue that these changes pose threats to the conventional forms of democracy (Strandberg 2006). These studies, which were organized as mega social science research projects initiated and funded by the national governments, aimed to evaluate democracy and power in a wide scale. All the Scandinavian governments (Denmark, Sweden and Norway) initiated such studies in the late 1990s, and they all raised concerns about the present state of democracy. Comparing the three studies, they share a conclusion that profound changes have taken place in the three Scandinavian democracies (Goul Andersen 2006; Amnå 2006; Selle and Østerud 2006; Rothstein 2009). However, the three studies also differ in the evaluations of the decline of the conventional model of democracy. The Danish research team, for example, argues that the observed changes should not be evaluated by standards too strongly linked to the institutional structure of the past (Togeby 2005). Meanwhile, Norwegians appear to be stronger committed to the conventional model of representative democracy and consequently also draw more pessimistic conclusions. Taking an ideal type as a starting point, the research team claims that ‘the parliamentary chain of government is 2 weakened in every link; parties and elections are less mobilizing; minority governments imply that the connection between election results and policy formation is broken; and elected assemblies have been suffering a notable loss of domain’ (Selle and Østerud 2006:25). Furthermore the research team claims that ‘the democratic infrastructure’ is declining, due to changes in civic organizations and the linkage between civil society and public sector (Tranvik and Selle 2003:185). These studies substantiate the challenges that the traditional model of input-driven democracy face, partly caused by reform driven by politicians themselves, and partly caused by new modes of governance and public management brought about as a response to increasing social complexity and in part by changes in society itself. But does this imply that democracy itself is weakening or only that the conventional input-based democratic legitimacy is declining? Can an increase in performancebased legitimacy compensate for the apparent decrease in input-based legitimacy? And are inputand performance-based legitimacy intertwined, conceptually and empirically? Sources of legitimacy ‘Legitimacy’, writes Bruce Gilley (2006:502), ‘is an endorsement of the state by citizens at a moral or normative level.’ It is conceptually distinct from political support which can be related either to the state or to the government of the day. On a practical level, though, the two may interrelate in the sense that legitimacy may be a fruit of long lasting political support, or political support in crucial moments, for example when a written constitution is formed. The very core of legitimacy is that citizens are willing to accept decisions and actions by the state even if they do not correspond with individual preferences or objectives (Gilley 2006). Even if the phenomenon can be fairly delimited and defined, the literature and perspectives on legitimacy are manifold and complex. In a later work, Gilley distinguishes between five different schools, based on how they understand the processes providing legitimacy (2009). First, there is the point of view that the sources of legitimacy are non-universal, and vary across both time and space. Positioned in this particularistic school, any attempts to generalize about the sources of legitimacy would be fruitless. The remaining four schools share a belief to some extent that sources of legitimacy are universal, but they argue that these sources vary extensively. In the sociological school, the main emphasis is on social and cultural conditions that give rise to positive sentiments about the state. These conditions can be related to deeper values such as religion, social trust, social capital, a national feeling of ‘happiness’ etc, but also more action-oriented characteristics like the level of political engagement and political interest are among the aforementioned sources. Moving on to a developmental school, one can see legitimacy as following from the organization, production and distribution of material well-being in a society. In that perspective, short and medium-term fluctuations in economic growth can have an effect on state legitimacy. The school labelled democratic represents a dominating strand of thoughts. For these theorists, the most important source of legitimacy is the extent to which states uphold an extensive and equal system of human rights, including civil, political, physical and social rights. Finally, a bureaucratic school can be identified, arguing that legitimacy is derived from the strength, effectiveness and due procedures of state institutions. Rather than siding with any of these schools of thought, Rothstein outlines ‘four distinct views’ about the sources of political legitimacy (2009:313). According to Rothstein, people accept the political authority of their leaders based in either tradition, their personal appeal and charisma, the government’s production of goods and services or in a belief in the fairness of the procedural mechanisms for selecting leaders and making decisions. Most of these ‘schools’ or ‘views’ on the sources of legitimacy can be related either to procedures or performance, or both. The developmental and bureaucracy schools resemble performance-based 3 legitimacy, as does the third source mentioned by Rothstein. The remaining three mentioned by Rothstein relate to procedural legitimacy, together with the democratic and sociological school. The literature in this field demonstrates various conceptions concerning how to interpret observed societal changes and how to understand the relative importance and exact relationship between procedural and performance-based legitimacy. Thus, Michael Hechter (2009:281) argues that the key determinant of the legitimacy of a state is the perceived fairness of the decision-making process rather than its provision of resources, opportunities, and outcomes. Others, like Guy Peters (2009, 2011), tend to see a more profound shift from input to output-democracy, arguing that there has been a shift from input-oriented forms of democracy (procedural) towards a form of democracy which is more tied to the outputs of policy-making (performance). Legitimacy is integral to societal consent with the exercise of political power. In the spirit of liberal democratic theory, traditional models of democratic governance tie political power to elective office and to democratic accountability, i.e. to the input side of the political system. Furthermore, in this institutional arrangement the public bureaucracy and much of sub-national government have the implementation of policy as their chief role. These roles which have been accorded to elected officials and political and administrative institutions are thus constitutional and normative; they define jurisdictions and institutional capabilities. While there is a profound normative stability in these arrangements, the empirical and analytical adequacy of this model is however a matter of empirical inquiry (Crozier 2010). Broadly speaking, the legitimacy of the state can be thought of as related either to its procedures or its performance. Procedural legitimacy is derived from the legality of the public administration and due process. Citizens, in this perspective, have confidence in the public bureaucracy because it sustains equal treatment and the public interest. Legitimacy related to performance, one other hand, is the result of the quality of services delivered; recipients support public services as long as they are satisfied with its services. But we do not know very much about the relationship between these two types of legitimacy. It would appear as if there is a negative correlation between them; bureaucracies prioritizing due process will not be very inclined to tailor services to individual preferences, hence the prospect of performance-based legitimacy would appear to be low. By the same token, bureaucracies emphasizing quality and cost-efficiency in service delivery are likely to adopt managerial models of administration towards that goal, and extensive managerial autonomy does not go very well with an organizational model which prioritizes due process (see Moore 1995). However, there is some evidence of a positive correlation between the two; studies conducted in the EU institutional context suggest that the strongest predictor of output-based legitimacy is, in fact, a high level of input legitimacy (Lindgren and Persson 2010). The proliferation of collaborative governance arrangements such as public-private partnerships and networks has gradually transformed the modus operandi of government at the same time as its traditional normative role in democratic governance has remained largely intact (Pierre 2009). Similarly, New Public Management reform with its emphasis on organizational efficiency and managerial autonomy has challenged the traditional model of political control and accountability (see Peters and Pierre, 2011). There have also been significant reforms undertaken to empower public service clients vis-à-vis public service institutions, e.g. in the form of quasi markets and customer choice models of service delivery (Pollitt and Bouckaert 2004). All of these developments are conducive to increasing performance-related legitimacy. More importantly in the present context, NPM reforms in many countries and service sectors have provided clients of public services an opportunity to choose among competing service producers, thus opening up a channel for the articulation of popular preferences at the output side of the political system. If we assume that this greater influence of clients on the services they receive leads 4 to more tailored services and therefore also to greater satisfaction with those services, then there is also strong reason to suspect that this will increase performance-based legitimacy. That having been said, there are several important aspects of the relationship between service delivery and legitimacy of political institutions that must be taken into account. First, while NPM reform may enhance satisfaction with service delivery, it also raises the pertinent question of whose legitimacy—the private contractor or the public bureaucracy—will benefit from market-based public service delivery. Guy Peters (2008:379) suggests that ‘as government loses control over functions considered to be public, it may lose the ability to effectively direct the society; it may lose the steering ability that constitutes the root of what we call government’ (Peters, 2008:379). To put this slightly differently, if NPM reform leads to greater customer satisfaction with services that, to smaller or greater extents, are no longer delivered by the public sector, how will this affect the legitimacy of political or administrative institutions? Secondly, and partly related to the previous comment, NPM reform and the customer-based model of service delivery have strengthened one type of accountability at the same time as they have weakened another; the more conventional form of accountability. As Brewer (2007:555) points out, ‘the consumerist model is based on a narrow perspective of what constitutes public accountability. By placing too much attention on customer satisfaction, important values of fairness and due process, which are fundamental to good governance and the citizenship status of individuals in their societies, may be undermined’. Thus, while customer satisfaction might be a valid measure of performance-related legitimacy, it says very little indeed about procedural legitimacy. Moreover, the literature of political science abounds with studies on value change and the development of citizens’ attitudes towards hierarchical institutions, and scholars point to a number of reasons why current generations are less deferent to political authorities and display lower trust in politicians than preceding cohorts. Dalton (1999) argues that processes of political and social change have been coupled with greater public expectations towards government, and as authorities have not been able to respond to these demands, an increasingly mobilised public has begun to demand a more open and participatory form of democracy. Inglehart’s (1999; 1997; 1977) well-known thesis on the ‘post-materialist’ value revolution similarly argues that social, economic and political security have enabled people to have high standards when evaluating politics and policies, which has brought about higher level of distrust towards conventional forms of governance and its representatives. However, neither scholars argue that democratic values have eroded and that democracy as a form of government does not enjoy public support anymore; on the contrary, the argument follows that the ‘cognitive mobilisation’ of people has led to an increased focus on democratic values and the political system. The fact that people challenge elites is not synonymous with a ‘value crisis’ which undermines the very foundations of Western regimes (Dalton 1999). This discussion cannot be omitted in our study of people’s attitudes towards local government as well, as we may well hypothesize that people’s attitudes towards democracy and the political systems as such may not be predicted by their (lack of) trust in politicians. In the midst of all these changes and developments we emphasize the critical role of political legitimacy in democratic governance. Public management reform is rarely assessed in terms of its impact on that legitimacy (but see Suleiman 2003). While NPM reform may strengthen performancebased legitimacy we need to know the degree to which it has an impact on the procedural legitimacy of the state. The bottom-line issue seems to be that while customer satisfaction and trust in service providers is not necessarily related to the public or private sector, procedural legitimacy remains critical to the public sector and cannot be transferred to for-profit organizations (Pesch 2008; Peters 2008). 5 Hence, the theoretical reasoning of this paper applies to all formal levels of government. In the following section, we aim to discuss and define some core variables in a planned study of performance-based legitimacy at local level. One of the appeals of addressing these issues at local government level is that our research then can draw on both large and small N studies providing variation in the dependent and independent variables while controlling for important variables related to national context (John 2008). This research design becomes all the more important as it could be argued that there are institutional factors that make performance-based legitimacy more important at local than at nationstate level, such as for instance the proximity to service providers. It could also be argued that the regulatory role of the nation-state (or the European Union) is less conducive to fostering performance-based legitimacy in the same way as public service delivery at the local and urban level can do. Moreover, the symbolic value of local government is less prominent than the one of national governments; its powers are less extensive, the link between the electoral process and government is less apparent, and the public interest in local government procedures is lower than for the national government. Hence, the legitimacy of procedural mechanisms of local government may well be perceived as less important than the actual services it delivers, as services are more visible than procedures. Moreover, we do not know to which degree performance-based legitimacy is tied to specific institutional levels, i.e. to what extent service recipients are knowledgeable about which specific institutions should be credited for specific services, or if performance-based legitimacy functions as a contributor to support for the state and the public sector in general. With a crossnational research design targeting local governments in two or more countries we can, to some degree at least, address these issues. Preparing the empirical analysis: the variables Following the above line of thought, it is relevant to ask how different groups of actors, for example in local government, understand legitimacy and how they judge the legitimacy in terms of procedural and performance-based legitimacy. Furthermore it is reasonable to ask how legitimacy is understood and judged within different institutional contexts like traditional agency management and new governance arrangements. In this section we identify a set of dependent and independent variables that form a part of the analytical framework for an empirical study on performance-based legitimacy at the local level. We begin this presentation by elaborating on our dependent variable, legitimacy. The present analysis does not claim to address all aspects of the highly complex phenomenon of legitimacy; nor does it attempt to include all those societal factors that might help explain the level of legitimacy for any political system. Instead, we are outlining a framework for analysis based on what we believe to be the most significant dependent and independent variables which form the contexts of our discussion on legitimacy. The Dependent variable: Legitimacy While a review of the literature on political legitimacy culminates in a vast number of approaches to measure procedural legitimacy, the measurement of performance-based legitimacy has been subject to the attention of academics to a lesser extent. However, we may argue that there are conceptual difficulties with several suggested approaches to measure input-based legitimacy as well, which have to be taken into account when designing a research framework. This section will elaborate on some approaches to operationalize legitimacy. To begin with, one can imagine two levels of legitimacy. Following Levi, Sacks and Tyler (2009), legitimacy can be both value-based and behavioural. Value-based legitimacy expresses a sense of obligation and willingness to obey government decisions regardless of their ideological orientation. This type of legitimacy translates into actual compliance with governmental regulations and laws, i.e. behavioural legitimacy. But not necessarily all actions grouped under behavioural legitimacy can be 6 traced back to values, as instinctive behaviour or fear may be as important as values to explain actual behaviour. Similarly, values do not guarantee certain behaviours as different barriers or obstacles may prevent people to doing the ‘right’ actions. For example, citizens may vote because they support the political system, or they may support the political system, but decide not to vote since they may not believe that the current political parties and representatives rule in a way which coincides with their preferences. Another possibility is that citizens may not support the political system, but vote since they believe that this is their only possibility to influence the system, alternatively, they may choose to vote for anti-establishment parties in an expression of discontent with the system or incumbent (local) government. Furthermore, values of liberal democracy are by nature tricky concepts to employ in citizen surveys, given the normative nature of the question. General definitions of values of liberal democracy may be ill-advised as it is very difficult to argue in a scientific manner that specific values can be 1) claimed to be universal and 2) necessary prerequisites for legitimacy, based on normative assumptions of which values represent democratic legitimacy. For the issue of universalism of values, one can refer to Easton’s (1965) requirement that values need to be shared by the population as a whole, and that these values need to be expressions of what is the ‘common good’ while individuals yield their own wishes and demands in favour of what they define as what is the best for the population as a whole. For the second point, we may encounter difficulties if we choose popular perceptions of what are values of democracy, such as freedom of speech and free elections, since such values may not actually represent people’s perceptions of legitimacy – their ideas of what constitute legitimate (local) government may be based on different values. These factors make values difficult to operationalize into meaningful measures of legitimacy. All in all it can be argued that there is a complex relationship between values and behaviour, as well as a complex relationship between attitudes and behaviour towards the system as such and/or the incumbent government. The latter two may often be confused with each other, and citizens’ values and actions may be associated with either the system or the incumbent government, or a fusion of both (See Easton 1965 for a discussion on the difference between diffuse and specific support). The same argument can be framed for political participation as acts of consent for the system: the very reason for participation may be exactly the opposite. Hence, we are compelled to distinguish between value-based legitimacy and behavioural legitimacy, as well as whether these are associated with the system or the current government. The key methodological challenges lie exactly within the measurability of such complex matters. When making performance-based legitimacy ready for empirical analysis in terms of questions for a questionnaire or an interview guide, one needs to pay special attention to several possible methodological problems. First, even if legitimacy conceptually is distinct from political support, exploring this field empirically probably would reveal that there is a gradual transition and to some extent interrelation and overlap between the two. Clearly relating an empirical observation (i.e. an answer to a posed question, etc) to one or the other will be difficult, and will require extensive considerations throughout the empirical research process. Maybe the most obvious point of departure for measuring legitimacy is to ask citizens to what degree they feel they trust government and elected officials, and attempt to measure trust and support for a selection of aspects of the system in itself. Examples of questions relating to inputbased legitimacy can be transparency and efficiency of local politics, accountability of elected officials, and whether local parties are able to tap into ordinary people’s desires and needs. Other useful measures of input-based legitimacy can be to measure degrees of political alienation, and whether people believe that their opinions matter in local politics and whether they feel that politicians are responsive to people’s opinions. When elaborating on such matters, Inglehart’s (1999; 1997; 1977) theory of post-materialist value change, as elaborated on in previous paragraphs, can provide a useful framework for analysis. Inglehart argues that ‘post-materalist’ citizens can be expected to experience a lower degree of political alienation than ‘materialist’ citizens, which 7 provides a point of departure for our analysis: will this also bring about higher confidence in the legitimacy of local government for ‘post-materialists?’ Another useful aspect to consider is Holmberg’s (1999) ‘home-team’ hypothesis, which suggests that political trust will be highest among voters whose (preferred) party is in power and lowest among those whose party is in opposition. It has to be pointed out that this dummy-measure can be argued to constitute a measure of specific rather than diffuse support, which must be taken into account when analyzing the results. Support can then be specified in subsequent survey items to measure perceptions of performancebased legitimacy as well; do people trust that local government will provide adequate services, how do they perceive the quality of the administration, and the accountability of bureaucrats? This analysis could for example depart from the idealized model of impartiality in implementing policy as suggested by Rothstein (2009). Independent variables In the following we intend to discuss a set of variables that we assume, based in the theoretical discussion above, to have an influence on performance-based legitimacy. New client-state exchanges. Some aspects of the claimed transformation of the public sector have been able to create alternative mechanisms for democracy (Peters 2009:8). In some national contexts and service sectors clients qua customers are offered extensive choice thus enabling them to tailor the services according to their needs and preferences. Based on the intentions behind these structures (Box et al. 2001; Lowndes et al. 2001; Vetter and Kersting 2003), one can assume that close proximity to service providers, for instance stakeholder representation or users’ boards, has a positive influence on performance-based legitimacy. Organisational structure. As we discussed earlier, the degree of autonomy that service providers have in relationship to the local authority is an essential element in describing the organisational form. As illustrated in figure 1, different organizational forms could be represented along a continuum where low degree of service provider autonomy implies direct political governance, and vice versa; high degree of autonomy implies a more indirect kind of political governance. Figure 1: Institutional forms and degree of service provider autonomy More specifically, we can distinguish between services delivered by the authority proper on the one hand, and services that are delivered by for-profit organizations, municipal companies or networks on the other. Thus, since it is widely believed that governance forms like partnerships and networks tend to propel the drift towards performance-based legitimacy (Peters 2010), we assume that these institutional variables yield different levels of legitimacy. Supervision and control. If democracy has shifted towards the output-side, accountability becomes all the more important for democracy (Peters 2009:3). Accountability reflects a commitment or willingness to accept the responsibility for one’s behaviour (Steets 2010:15). This accountability can be based in norms, spontaneous and something taken for granted by politicians and bureaucrats 8 (Dobel 2005, Olsen 2005). But in the aftermath of New Public Management, to an increasingly extent, systems of supervision and control have become institutionalized. The general development described as the ‘audit society’ (Power 1997) is recognized at the local governmental level in many countries (Helgøy and Serigstad 2004; Karlsson 2009). This development connects to increased devolution, management discretion and competition introduced as New Public Management reform has been implemented worldwide as safeguards against corruption and unethical behaviour (Dobel 2005; Frederickson 2005). National government regulations vary between countries, however, and there are significant variations among municipalities in terms of how much supervision and control is taking place and how systematic and communicated these efforts are (for Norway see KRD 2009). The impact that those activities have on procedural and performance-based legitimacy in local governments will therefore be an empirical question. Likewise, it is an open question whether institutionalized systems for supervision and control surpass more informal and norm based principles of accountability (Lundquist 1998; Pharr and Putnam 2000). Organizational functions. So far we have elaborated on networks and partnerships as if they represent a homogeneous type of public-private collaboration. However, as Julie Steets (2010) reminds us, these structures differ widely in terms of their organizational functions. This observation has implications for both accountability principles and legitimacy. By disentangling partnerships into different types distinguished by their organizational function, Steets shows that rule setting/regulating and implementing partnerships require more extensive systems for accountability than advocacy and awareness-raising partnerships, the latter operating more on the input side then the two first mentioned (Steets 2010). The argument here is simply that what organizations, partnerships and networks do in terms of organizational functions is an important variable in an empirical study of performance-based legitimacy. Local government systems. Variation in average municipal size, local government autonomy and financial strength make important differences, and should also be taken into account. Large local governments are able to organise their core services (eg. water and sewage systems, waste, child care, special education, social services) within the municipal jurisdiction, whereas in systems of smaller average municipalities collaboration with neighbouring municipalities becomes essential in order to produce core services. Even between as similar countries as Sweden and Norway, there are essential differences in this regard. While national government is very much present in the Norwegian context, stressing the local government role as providers of national welfare services (Fimreite and Tranvik 2010), the much larger average municipalities with greater autonomy in Sweden (Bäck and Johanson 2010) is likely to result in more increased focus on the local agenda. This may help create a closer link between the political system and the citizens in the Swedish municipalities than is the case in Norway which, in turn, may influence the democratic legitimacy in the direction of a stronger dependence on output legitimacy in the Norwegian than in the Swedish municipalities. Previous studies show what municipal size matters when citizens form opinions on whether they regard municipal authorities as legitimate (Denters 2002). 4. Summing up This paper has been motivated by two main questions. First, it is more or less common sense that performance in one way or another is a source of legitimacy, but has mainly been seen as a less important and supplementary source compared to the input-based legitimacy provided by for example elections and due bureaucratic procedures. With New Public Management and similar reform efforts, new governance arrangements involving private or civil sector have made many of the traditional mechanisms ensuring input legitimacy more indirect and perhaps even less relevant. Moreover, several scholars emphasize that social and economic changes have brought about less deferent attitudes towards authorities, which provides an interesting theoretical framework for the 9 part of this study which focuses on citizens’ attitudes. These observations, well documented by the Scandinavian power and democracy studies we referred to in previous paragraphs, leads to the important question of whether or not performance-based legitimacy can compensate for the contended lack of legitimacy created at the input side of the policy circle. Our second main question relates to the relationship between procedural and performance-based legitimacy. Maximizing input based legitimacy may mean that bureaucracies prioritize due processes. In doing so, individual preferences and tailor services probably will not be high on the agenda. This may mean that the two sources of legitimacy are competing sources, and that we should not expect the two sources being equally important. Both these questions have empirical answers. Standing in front of a research project aiming to dwell on these questions, we have introduced a set of variables that, from our perspective, need to be included in such a study. There variables are summed up in the figure below. Figure 2: Some variables possibly explaining level of performance-based legitimacy The research outlined here should providing interesting accounts of the changing nature of political and democratic legitimacy. As mentioned earlier in the paper, performance-based legitimacy is in itself not a new phenomenon but changes within the state and its interfaces with the surrounding society tend to accord growing importance to output-based legitimacy and, arguably, a decreasing significance of representation as a source of legitimacy. There has been much theorizing on these issues. The research outlined here will provide empirical context to theory and help us better understand the sources of output-based legitimacy and how this form of legitimacy relates to inputbased legitimacy. 5. References 10 Amnå, E. (2006), ‘Playing with fire? Swedish mobilization for participatory democracy’, Journal of European Public Policy 13:587-606. Andersson, S. and T. Bergman (2008), ‘Controlling Corruption in the Public Sector’, Scandinavian Political Studies 32:45-70. Bäck, H. and V. Johansson (2010), ‘Sweden’, in Goldsmith, M .J. and E. P. Page (eds), Changing Government Relations in Europe (London: Routledge). Bang, H. P. (2007), ‘Critical theory in a swing: Political consumerism between politics and policy’, in M. Bevir and F. Trentman (eds), Governance, consumers and citizens: Agency and resistance in contemporary politics (Basingstoke: Palgrave), 191-230. Box, R. C., G. S. Marshall, B. J. Reed and C. M. Reed (2001) ‘New Public Management and Substantive Democracy’, Public Administration Review 61:608-19. Brewer, B. (2007), ‘Citizen or Consumer?: Complaints Handling in the Public Sector’, International Review of Administrative Sciences 73:549-56. Christensen, T and P. Lægreid (2005), ‘Trust in Government: The Relative Importance of Service Satisfaction, Political Factors and Demography’, Public Performance and Management Review 28:487-511. Crozier, M. P. (2010), ‘Rethinking Systems: Configurations of Politics and Policy in Contemporary Governance’, Administration and Society 42:504-25. Dalton. R. and B. Wattenberg (2000), Politics Without Partisans (Oxford: Oxford University Press). Dalton, R. (1999), ‘Political support on advanced industrial societies,’ in Norris, P. (ed.), Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Governance, Oxford: Oxford University Press Denters, B. and P. J. Klok (2003), ‘A new role for Municipal councils in Dutch Local Democracy?’, in N. Kersting and A. Vetter (eds), Reforming Local Government in Europe. Closing the gap between Democracy and Efficiency (Opladen: Leske and Budrich). Denters, B., O. Gabriel and M. Torcal (2007), ‘Political confidence in democracies,’ in van Deth, J.W, J.R. Montero and A. Westholm (eds.), Citizenship and Involvement in European Democracies: A Comparative Analysis, London: Routledge Denters, B. (2002), ‘Size and Political Trust: Evidence from Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway and the United Kingdom,’ Environment and Planning: Government and Policy, vol. 20. Dobel, J.P. (2005), ‘Public Management as Ethics’, in E. Ferlie, L.E. Lynn and C. Pollitt (eds), Public Management (Oxford: Oxford University Press). Easton, D. (1965), A systems framework for political analysis (Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall). Fimreite, A.L. and T. Tranvik (2010), ‘Norway’, in Goldsmith, M .J. and E. P. Page (eds), Changing Government Relations in Europe. London: Routledge. Frederickson, H. G. (2005), ‘Public Ethics and the New Managerialism: An Axiomatic Theory’, in H. G. Frederickson and R. K. Ghere (eds), Ethics in Public Management (New York: M. E. Sharpe). Gilley, B. (2006), ‘The Meaning and Measure of State Legitimacy: Results for 72 Countries’, European Journal of Political Research 45:499-525. Gilley, B. (2009), The Right to Rule: How States Win and Lose Legitimacy (New York: Columbia University Press). Goul Andersen, J. (2006), ‘Political power and democracy in Denmark: decline of democracy or change in democracy?’, Journal of European Public Policy 13:569-86. Haus, M. and D. Sweeting (2006), ‘Local democracy and political leadership: Drawing a map’, Political studies 54:267-88. Haus, M., H. Heinelt and M. Steward (eds) (2004), Urban Governance and Democracy: Leadership and community involvement (London: Routledge). Hechter, H. (2009), ‘Legitimacy in the modern world’, American Behavioral Scientist 53:279-88. Helgøy, I. and S. Serigstad (2004), ‘Tilsyn som styringsform i forholdet mellom stat og kommune’. Notat 9-2004 (Bergen: Rokkansenteret). Holmberg, S. (1999), ‘Down and Down We Go: Political Trust in Sweden,’ in Norris, P. (ed.), Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Governance, Oxford: Oxford University Press Inglehart, R. (1999), ‘Postmodernization erodes respect for authority, but increases support for democracy,’ in Norris, P. (ed.), Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Governance, Oxford: Oxford University Press Inglehart, R. (1997), Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies, Princeton University Press Inglehart, R. (1977), The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics, Princeton: Princeton University Press John, P. (2008), ‘Why Study Urban Politics?’, in J. Davies and D. Imbroscio (eds), Theories of Urban Politics (2nd. edn) (London: Sage). Karlsson, A. (2009) Institutionalisering av ansvar i kommunal revision (PhD dissertation) (Jönköping: Internationella Handelshögskolan). Katz, R. S. and P Mair (1995), ‘Changing Models of Party Organization and Party Democracy: The Emergence of the Cartel Party’, Party Politics 1:5-28. Kim, S-E. (2008), ‘The Role of Trust in the Modern Administrative State: An Integrative Model’, Administration and Society 40:586-620. KRD (2009): 85 tilrådingar for styrkt eigenkontroll I kommunane. Rapport. Oslo: Kommunal- og regionaldepartemetnet. Levi, Margareth, Audrey Sacks, and Tom Tyler (2009), ‘Conceptualizing legitimacy, measuring legitimating beliefs’, American Behavioral Scientist 53:354-75. Lindgren, K-O. and T. Persson (2010), ‘Input and output legitimacy: synergy or trade-off? Empirical evidence from an EU survey’, Journal of European Public Policy 71:449-67. Lowndes, V., L. Pratchett and G. Stoker (2001), ‘Trends in Public Participation: Part 1 – Local Government Perspectives’, Public Administration 79:205-22. Lundquist, L. (1998), Demokratins väktare: Ämbetsmännen och vårt offentliga etos (Lund: Studentlitteratur). Montin, S and M. Granberg (2007), ‘Local governance in Sweden’ (paper presented at the ECPR General conference, Pisa). Moore, M. H. (1995), Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press). Olsen, J. P. (2005), ‘Maybe it is time to rediscover bureaucracy?’, Jornal of Public Administration Research and Theory 16:1-24. Pesch, U. (2008), ‘The Publicness of Public Administration’, Administration and Society, 40, 170-93. Peters, B. G. (2008), The Politics of Bureaucracy (6th. edn.) (London: Routledge). Peters, B. G. (2010), ‘Bureaucracy and Democracy’, Public Organization Review 10:209-22. 12 Peters, B. G. (2011), ‘Bureaucracy and democracy: Towards result-based legitimacy?’, in J-M. EymeriDouzans and J. Pierre (eds), Administrative Reforms and Democratic Governance (London: Routledge). Peters, B. G. and J. Pierre (2011), ‘Multiple Forms of Accountability: Complementary, Competitive, or Just Different?’ (paper presented at the American Society for Public Administration conference, Baltimore). Pharr, S. J., and R. D. Putnam (eds) (2000), Disaffected democracies: What's troubling the trilateral countries? (Princeton: Princeton University Press). Pollitt, C. and G. Bouckaert (2004), Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis (Oxford: Oxford University Press). Power, M (1997), The audit society (Oxford: Oxford University Press). Przeworski, A. and H. Teune (1982), The Logic of Comparative Inquiry (Malabar, FL: R. E. Krieger). Rhodes, R. A. W. and J. Wanna (2007), ‘The Limits to Public Value, or Rescuing Responsible Government from the Platonic Guardians’, Australian Journal of Public Administration 66:40621. Røiseland, A (2006), ‘Demokratiets infrastruktur i forfall?, Tidsskrift for samfunnsforskning. 47(3): 423-433. Rothstein, B. (2009), ‘Creating Political Legitimacy: Electoral Democracy versus Quality of Government’, American Behavioral Scientist 53:311-20. Rothstein, B. (2009), ‘Creating political legitimacy: Electoral democracy versus quality of government’, American Behavioral Scientist 53:311-30. Scharpf, F. W. (1999). Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic (Oxford: Oxford University Press). Selle, P. and Østerud, Ø. (2006), ‘The eroding of representative democracy in Norway’, Journal of European Public Policy, 13(4): 551-568. Steets, J. (2010), Accountability in public policy partnerships (London: Palgrave). Strandberg, U. 2006. Introduction: historical and theoretical perspectives on Scandinavian political systems. Journal of European Public Policy, 13(4): 537-550. Suleiman, E. (2003). Dismantling Democratic States. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Togeby, L. (2005), ‘Hvorfor den store forskel? Om den danske magtudrednings konklusioner om demokratiets tilstand i Danmark omkring årtusindskiftet, Tidsskrift for Samfunnsforskning 46:55-60. Tranvik, T. and P. Selle (2003), Farvel til folkestyret? Nasjonalstaten og de nye nettverkene (Oslo: Gyldendal). Vabo, S. I. and J. Aars (2011), ‘New Public Management reforms and democratic legitimacy: Attitudes among councillors in West European local governments’, Local Government Studies, forthcoming. Vetter, A. and N. Kersting (2003), ‘Reforming local government: Heading for efficiency and democracy’, in N. Kersting and A. Vetter (eds), Reforming Local Government in Europe. Closing the gap between Democracy and Efficiency (Opladen: Leske and Budrich). 13