Clefs - Cloudfront.net

advertisement

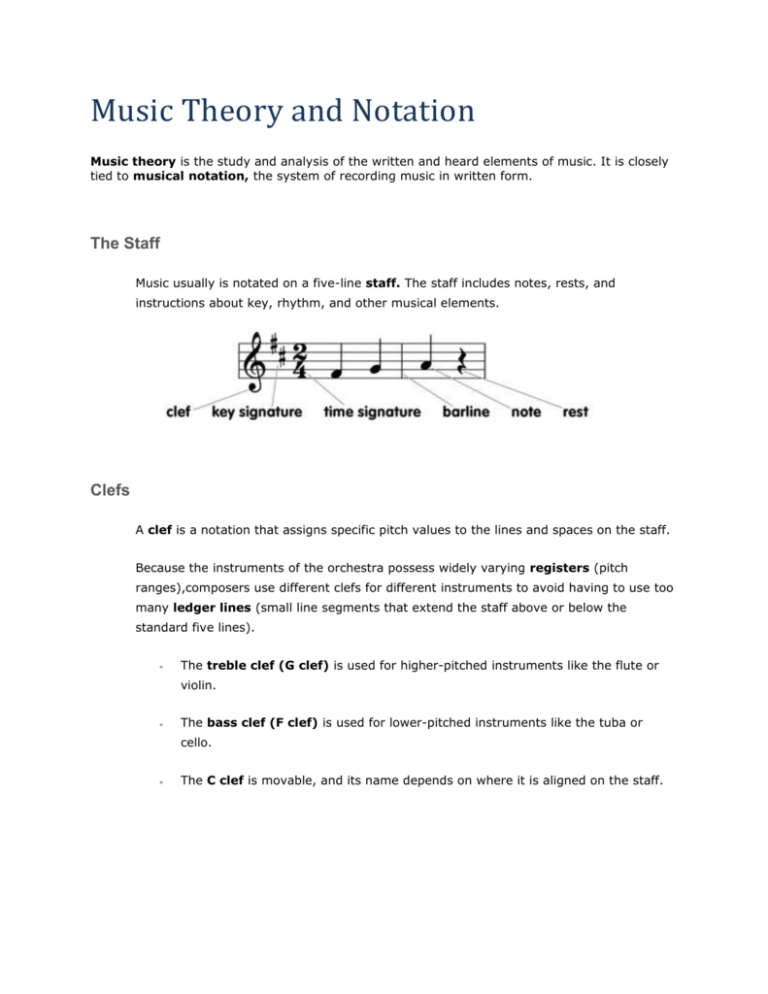

Music Theory and Notation Music theory is the study and analysis of the written and heard elements of music. It is closely tied to musical notation, the system of recording music in written form. The Staff Music usually is notated on a five-line staff. The staff includes notes, rests, and instructions about key, rhythm, and other musical elements. Clefs A clef is a notation that assigns specific pitch values to the lines and spaces on the staff. Because the instruments of the orchestra possess widely varying registers (pitch ranges),composers use different clefs for different instruments to avoid having to use too many ledger lines (small line segments that extend the staff above or below the standard five lines). The treble clef (G clef) is used for higher-pitched instruments like the flute or violin. The bass clef (F clef) is used for lower-pitched instruments like the tuba or cello. The C clef is movable, and its name depends on where it is aligned on the staff. The following staves show where the same pitch (middle C) appears on different clefs: Music for instruments with a wide range (such as the piano) is notated on the grand staff, which combines the treble clef and the bass clef: Rhythm, Notes, and Rests Rhythm refers to the arrangement of beats in a piece of music. Rhythm is expressed graphically with notes and rests (durations of silence in which no notes are played). Notes are named based on their duration. The longest note in conventional use is the whole note; the shortest in conventional use is the 128th note: Rests are named in a manner similar to notes: Adding a dot to a note or rest increases the duration of that note or rest by one half: A tie over two or more notes of the same pitch indicates that the notes under it should be held or sustained: Sometimes, composers break rhythms into three equal parts called a triplet. There are also quintuplets, septuplets, and other groupings, collectively called tuplets. Meter and Time Signature Meter is the organization of rhythm into equal groups called measures or bars. Meter organizes the rhythm of a piece of music in the context of a regular pulse or beat. The composer uses two numbers called the time signature to indicate the meter of a piece of music. The top number tells the number of beats per measure; the bottom number indicates the time value of each beat in the measure. For example, in 6/8 time, there are six beats per measure, and each beat is an eighth note. The following are some standard time signatures: Two of the frequently used standard time signatures are abbreviated with symbols: Most time signatures in Western music are duple (the number of beats per measure are divisible by two) or triple (the number of beats per measure are divisible by three). Some time signatures are irregular and cannot be described as duple or triple. Two common irregular time signatures are 5/4 time and 7/8 time: Pitch Pitch refers to the sound frequency of a note (i.e., whether the note is high or low). In Western music, there are 12 named pitches, which together are called the chromatic scale. Some pitches have two names—for example, C and D are the same pitch. Such pitches are called enharmonic equivalents. The name given to an enharmonic pitch depends on notation and key. The space between two adjacent pitches in the chromatic scale is called a half step (also known as a semitone). Two semitones equal one whole step or whole tone. Accidentals are symbols used in musical notation to raise or lower the pitch of specific notes: A sharp raises a note a half step. A flat lowers a note a half step. A double sharp raises a note two half steps. A double flat lowers a note two half steps. A natural cancels any of the above accidentals and returns a note to its “natural” pitch. The space between a given pitch and the next pitch with the same letter name (for example, from C to C or from F to F) is called an octave. Scales A scale is an ascending or descending series of pitches. The pitches that make up a scale are called degrees, and each is assigned a name and number. From lowest to highest, the scale degrees are called the tonic (I), supertonic (II), mediant (III), subdominant (IV), dominant (V), submediant (VI), and leading tone (VII). The name of a scale is determined by its starting pitch and its key signature. Most Western scales consist of a series of whole steps and half steps in a specific order. The two most common Western scales are the major scale and the minor scale. There are three types of minor scales: Natural minor: The basic form of a minor scale (the c minor scale above is natural minor). Harmonic minor: A minor scale with the seventh degree elevated a half step. Melodic minor: A minor scale with the sixth and seventh degrees elevated a half step each. Other types of scales have been used throughout the history of Western music: Pentatonic scale: A five-tone scale widely used in indigenous folk music around the world. Whole-tone scale: A six-tone scale with a whole step between adjacent notes. Debussy and other Impressionist composers explored uses of this scale in the late 1800s. Octatonic scale: An eight-tone scale composed of alternating whole steps and half steps between adjacent notes. The octatonic scale came into widespread use in the 20th century. Key and Key Signature In Western music, most pieces are written in a key—a specific pitch that provides a tonal center or point of focus for the piece. A single piece of music may switch, or modulate, among several keys over its course. Often, a piece will make several modulations and then finish in the key in which it started. The key signature is a visual indication of key, placed on the staff at the beginning of a piece of music that shows which notes on the staff are sharp or flat for the duration of the piece. The composer may override the key signature by placing accidentals in front of individual notes. Each major key has a relative minor key that shares the same key signature, just as each minor key has a relative major key that shares the same key signature. For example, F major has one flat, as does its relative minor, d minor. A diagram called the circle of fifths displays these relationships among the keys in visual form: Intervals An interval is the space between any two pitches. Intervals are described with a numerical measure that counts the number of semitones that each interval spans (counting both the top and bottom pitches). Numerically, an interval may be described as a second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth (octave), and so on. Intervals also are described in terms of quality. An interval may be: Perfect (P): An interval whose constituent pitches appear in both the major and minor form of a given scale. For example, the interval between C and G is called a perfect fifth because the pitches C and G appear in both the C major and c minor scales. The only intervals that may be perfect are the fourth, fifth, and eighth (octave). Major (M): An interval whose constituent pitches appear in the major form of a given scale. Seconds, thirds, sixths, and sevenths may be major. Minor (m): An interval whose constituent pitches appear in the minor form of a given scale. Seconds, thirds, sixths, and sevenths may be minor. Diminished (d or °): A perfect or minor interval that has been reduced by a semitone. Augmented (A or +): A perfect or major interval that has been increased by a semitone. The same interval may have different names depending on the context in which it appears. For example, the tritone is a special interval that spans three whole tones. The tritone maybe described as either an augmented fourth (A4) or diminished fifth (d5). The following staves show the intervals from a minor second to a major ninth: Harmony and Dissonance Intervals are an integral part of harmony, a broad concept that relates to the use of simultaneous pitches in music and the way such relationships are organized over time. Whereas melody refers to the “horizontal” aspects of music (i.e., notes played in sequence), harmony refers to the “vertical” aspects (i.e., notes played together). Certain intervals, such as the major third, perfect fourth, and perfect fifth, sound “pleasant” or “stable” to the ear. These intervals form the basis of much traditional Western harmony. Other intervals, such as the tritone and major seventh, create a harshness or discordance referred to as dissonance. The use of dissonance in Western music has become gradually greater over the course of history. Chords A chord is a group of three or more pitches that sound simultaneously. The intervals between the notes within a chord determine the chord quality. Chords, like intervals, may be: M major m minor ° diminished + augmented In addition, certain types of chords may be: Mm major-minor half-diminished A triad is a chord that contains three pitches separated by major or minor thirds. A chord with four pitches separated by major or minor thirds is called a seventh chord. Triads and seventh chords form the basis of harmony for the vast majority of traditional Western music. The following staff shows several chords built on the note C. The notations in blue indicate the intervals between the notes within each chord: Tempo The tempo of musical composition is the speed at which it is played. Tempo and meter are closely connected. Tempo establishes the relationship between meter and actual time and thus affects how the meter and time signature of a composition sound to the ear. If a piece in 6/8 time is played at a slow tempo, the ear tends to perceive six beats per measure; if played at a fast tempo, the ear tends to perceive only two beats per measure. Musicians often use a device called a metronome to keep track of tempo. A metronome marks time by making a regular ticking or beeping sound a specified number of beats per minute. Often, tempo is described in terms of metronome number or metronome mark (M.M.), i.e., the number of ticks or beats per minute. Use of metronome marks enables the musician to determine tempo accurately with a metronome. Alternatively, a composer may allow more casual interpretation of tempo by using only suggested ranges of beats per minute. The composer can use tempo marks to change tempo throughout the course of a musical composition. These marks often take the form of descriptive terms from Italian, including: Largo: very slow (M.M.=40–60) Larghetto: very slow, but faster than largo (M.M.=60–66) Adagio: slow (M.M.=66–76) Andante: somewhat slow; a leisurely walking tempo (M.M.=76–108) Moderato: medium tempo; not particularly fast or slow (M.M.=108–120) Allegro: fast (M.M.=120–168) Presto: very fast (M.M.=168–208) Prestissimo: as fast as possible (M.M.>208) Dynamics Dynamics are directions, written in a piece of music, that indicate the volume at which a note or musical passage should be played. Composers typically indicate dynamics using abbreviations for a number of Italian terms: piano-pianissimo: extremely soft pianissimo: very soft piano: soft mezzo piano: moderately soft mezzo forte: moderately loud forte: loud fortissimo: very loud forte-fortissimo: extremely loud Expression and Articulation Expression marks are symbols or words placed in written music to provide further information about how the composition should be played. Expressions often are written in Italian, although composers sometimes use their native languages as well. Some common expressions include: Cantabile (cant.): singing, flowing, melodic Dolce: sweetly or gently Espressivo (espr.): expressive; “play out” Legato (leg.): evenly; notes should be fluid and continuous, and without accent Marcato (marc.): notes should be heavily accented and percussively attacked Staccato (stacc.): notes should be short and abbreviated Tenuto (ten.): notes should be sustained and slightly attacked The above expressions sometimes are modified with additional terms from Italian: Molto: very Moltissimo (moltiss.): extremely Poco: a little Pochissimo (pochiss.): a tiny amount Articulation marks provide information about attack and decay —the beginning and dying away of the sound of a note or a group of notes. Common articulation marks include: Themes, Motifs, and Structures Most compositions are structured around recurring melodic or rhythmic passages called themes or subjects. A composition may also feature a number of recurring motifs — shorter fragments of melody or rhythm, often derived from the composition’s themes. The composer usually does not notate themes and motifs explicitly in a piece of written music. Music scholars analyze the structure of a piece by labeling each distinct musical passage or theme with a letter. For instance, a piece that begins with a theme (A); then moves to another, different, theme (B); and then returns to the initial theme (A) is said to be in ABA form. Two common structures in Western music are the rondo form and the sonata form. Rondo form: A structure that starts with a primary theme that returns between contrasting sections. A rondo with two contrasting sections has ABACA form; one with three sections has ABACADA form. A rondo may have any number of contrasting sections. Sonata form: A form that became the standard form for the first movements of pieces in the Classical and Romantic eras. The sonata form typically includes four sections: Exposition: An opening section that generally presents two themes; Development: A section that expands upon and evolves the themes of the exposition; Recapitulation: A section that repeats the themes of the exposition unaltered; and Coda: A concluding section that lends resolution or a sense of finality.

![The Average rate of change of a function over an interval [a,b]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/005847252_1-7192c992341161b16cb22365719c0b30-300x300.png)