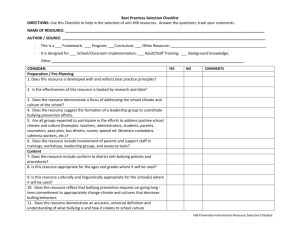

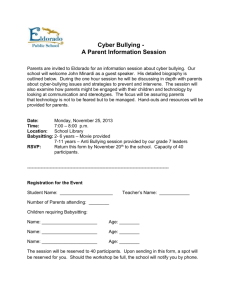

Preventing School Bullying

advertisement