Tracing_History_in_the_Saharan_Desert_Landscapes_summary

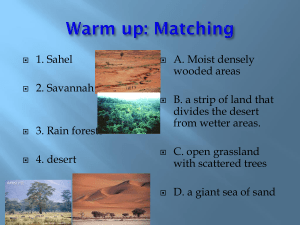

advertisement

1 Tracing History in the Saharan Desert Landscapes By Professor David Mattingly and Dr Martin Sterry, University of Leicester, UK Most maps of early African civilisations show the Sahara as a vast empty space. It has become the orthodox position to consider this as virtually impassable territory until the Islamic era. Such assumptions have been possible due to the generally underdeveloped state of archaeological and historical research in the Sahara. The ERC funded Trans-SAHARA project is designed to challenge the idea of an empty and unconnected Saharan world in preIslamic times and at the same time to provide a new framework for writing the history of Saharan communities. Our project builds on a programme of fieldwork I initiated on a people called the Garamantes in the Libyan Sahara. The Garamantes can now be recognised as one of the first Sahara civilisations, with socio-economic interconnections across the Sahara with the other precocious states of the Mediterranean and Sub-Saharan zones. This creates a new paradigm for the study of African civilisation. The heartlands of the Garamantes lay in a long linear depression known as Wadi al-Ajal, between a sand sea and a cliff-like escarpment. Their civilisation spanned the 1st millennium BCE and 1st Millennium CE. When I first started work in Fazzan, there were just a handful of identified Garamantian settlements. Our work has identified a complex hierarchy of permanent settlements (towns, villages and hamlets), 100s of ancient underground irrigation channels known as foggaras, several hundred thousand pre-Islamic burials and a rich and diverse material culture that incorporated imports from the Mediterranean world and SubSaharan Africa. In another oasis zone related to the Garamantes close to Murzuq, an area of 2500km2, we have located 158 settlements, 184 cemeteries, 30 km2 of fields, plus a variety of irrigation systems. Some of the sites are very large indeed and with an urban scale of complexity. We have mapped many fortified settlements known as qsur, or qasr to use the singular form, which sit in the middle of traces of abandoned gardens with cemeteries on their outskirts. Clearly a limitation with the satellite image analysis is that although we can detect morphological similarities between the sites, we cannot be certain from the imagery alone of their relative date. However, the vast majority of qsur that we were able to visit on the ground appeared to be Garamantian from the surface pottery recovered and this has now been confirmed by the results of a programme of AMS radiocarbon dating. The radiocarbon dates are very consistent, the majority falling in the Garamantian era. The combination of the remote sensing and dating programme has provided us with a way of modelling Garamantian demographic changes, illustrated in the lecture by using monte carlo simulation and kernel density estimates in a GIS model. We have confirmed the conclusions of my earlier work that the Garamantes were a sophisticated society, built around large and populous oasis communities, practising irrigated agriculture on a large scale and trading with partners to north and south of the Sahara. A key issue confronting the Trans-SAHARA project has been whether this sort of development was unique to the Garamantes, or whether oasis agriculture and trade were more widespread phenomena in the pre-Islamic Sahara. To test the exceptionality or otherwise of the Garamantes, we have now expanded our field of study further and are conducting a thorough review of Saharan oases and what is known of their origins. A significant number of oases can now be confirmed as having pre-Islamic origins. It is apparent that there was a broad east-west chronology of oasis formation within the Sahara, though the dates are not yet very precise for some phases. There is evidence for 2 initial oasis development in the Western Desert of Egypt as early as the 3rd and 2nd millennia BCE and oasis communities, as the Garamantes demonstrate, were well established in the Central Sahara by the end of the 1st millennium BCE. In the early centuries CE, quite a number of Roman forts in the frontier zone of Roman Africa were established at key oasis locations. Our presumption now is that these forts gravitated to places where oasis development had already occurred, rather than the other way round. Finally, there are many other oases in the western and southern Sahara that are presumed to have been inhabited only from the Islamic period, but our work throws serious doubt on to this assumption. Our research opens a possibility that pre-Islamic Saharan societies were far more complex and connected and incorporated both sedentary and pastoral elements. To test this hypothesis, our most recent work is focussing on Wadi Draa in the Moroccan Sahara, south of the Atlas mountains. Here again we have been able to detect large numbers of well-preserved settlements on satellite imagery. These appear to span from pre-Islamic times to the early modern period. As in the Libyan Sahara, the pre-Islamic activity seems to be characterised by certain distinctive tomb types, some complex hillfort occupations and early oasis development, possibly supported by the use of foggara irrigation technology. If our next phase of AMS dating work on this region confirms the early origins of agriculture and sedentary settlement here, then it also strengthens the argument that similar features detected on satellite imagery in relation to Tunisian and Algerian oases should also be considered of potentially early date. Our analyses have not only been concerned with the pre-Islamic era, but also sought to enhance knowledge and understanding of the Sahara in the medieval period. When the Garamantian capital at Jarma declined in late antiquity, its political and economic dominance was supplanted by the oasis of Zuwila in eastern Fazzan. This site provides a good example of another type of analysis that is sometimes feasible from the combined evidence of sateliite imagery, air photographs, and other archaeological data. The following images show how we can pick apart the palimpsest landscapes detected from satellite imagery to tell the urban biography of a Saharan centre. Zuwila also illustrates the fragility of Saharan heritage. It is apparent that even without the political instabilities and insecurity of recent years, Saharan archaeology is facing massive threats. Modern development linked to oil exploration has for long been one source of damage to Saharan archaeology, but its impact is dwarfed by the destruction of heritage due to the expansion of modern settlements and new agricultural schemes as can be seen by how much of the main settlement core of ancient Zuwila has been lost. We have seen repeated examples in our mapping work of the encroachment of bulldozing, construction, planting schemes and quarrying across the standing remains of substantial settlements. One of the most destructive acts against Libya’s cultural heritage of recent years was due to targeted Islamic extremism, involving a famous series of mausolea at Zuwila, long presumed to have been the tombs of the Islamic Banu Khattab dynasty. Our AMS dating programme has recently confirmed a 10th-century date for these extraordinary and unique monuments. But we recently received reports that the tombs have been demolished by Salafists, an act of vandalism confirmed by a new satellite image. Such incidents underscore the importance of recording and dating sites, but it is even more crucial that these results are communicated to the local communities for whom they should represent valuable cultural assets. It is only through their involvement that we can hope to secure better protection for this amazing Saharan heritage.