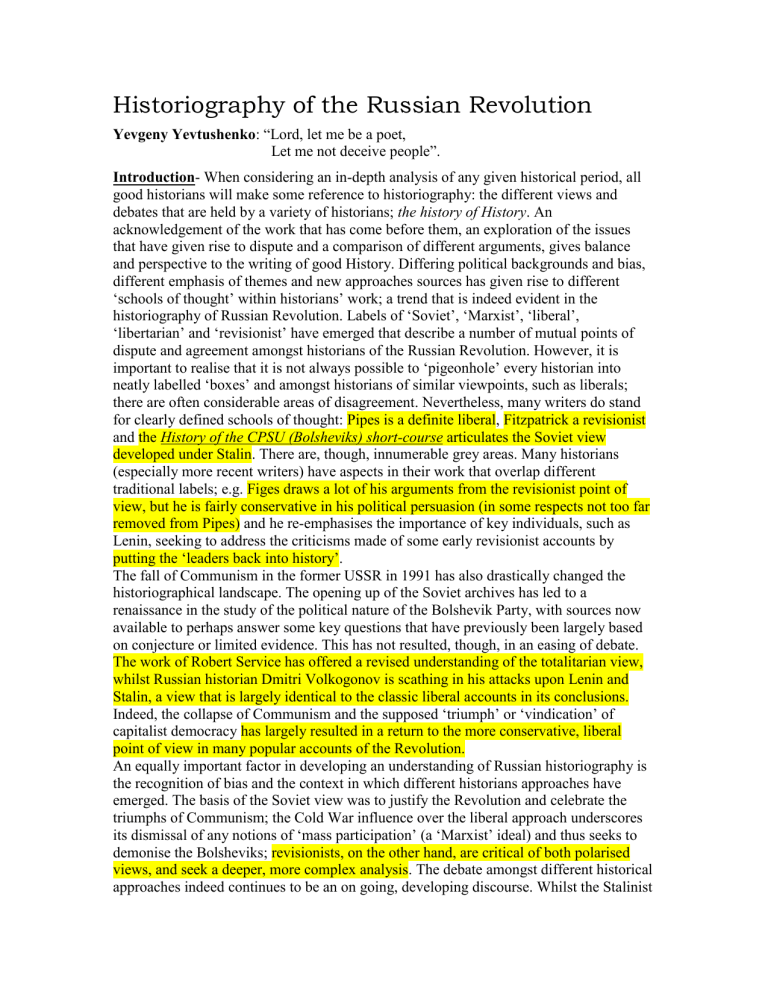

Historiography of the Russian Revolution

advertisement