References

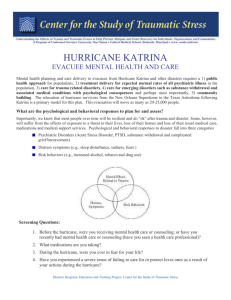

advertisement

Ten years ago, Hurricane Katrina made landfall in Louisiana on August 29, 2005. The category three hurricane with sustaining winds of 100-140 mph killed over 2000 people destroyed 100,000 homes and flooded 80% of New Orleans (Most, 2015). Although the storm itself was devastating, the aftermath was even more traumatic for those who survived. Patients from the New Orleans area faced medical care challenges. Tens of thousands of New Orleans evacuees required urgent medical care. More than 200,000 had chronic conditions needing ongoing management, the most common reason for care in evacuation centers. In the rush to evacuate, many left home without documents, medications, and other essentials. Even those who had their medications with them were separated from their health care providers and, in some instances, their families. Responding clinicians were challenged with assessing unfamiliar and ill evacuees without the benefit of their medical charts. (Brown, et al., 2007, p. S136-7) As stated, most people sought medical attention for their pre-Katrina conditions or medication needs than ones inflicted by the trauma of the storm itself. Many hospitals in the area had either limited operations or were closed due to flooding and infrastructural issues. These patients were left without access to their medical records. At that time, most facilities were still operating on mostly paper systems. “Unfortunately, many facilities were not prepared for this magnitude of destruction, and had no system in place to manage the potential for a total loss of all medical records” (Smith & Macdonald, 2006, p. 8). Other facilities were forced to handle the influx of new patients that had never been seen before at their facilities. “All patients presenting to hospitals during these events will require identification (raising the issue of how hospitals and healthcare facilities will cope with unidentifiable patients), allocation of medical records (and some retrieval of existing records), and appropriate patient tracking throughout the healthcare 1 facility” (Smith & Macdonald, 2006, pp. 8-9). Medical records that were not initial destroyed were seen floating in the contaminated flood waters. “Close to one million people displaced by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita had destroyed medical records, making it difficult for clinicians to provide appropriate treatment or medication prescriptions following the disaster (Cadence Group 2005)” (Smith & Macdonald, 2006, p. 9). Patients seeking medical attention had to have new medical records created, and some point checked against the surviving patient records for duplications and merged if possible. The entire medical scenario was a disaster within a disaster. Lessons can be learned from how the Department of Veteran’s Affairs responded. They had a regional data warehouse that contained clinical data that was regularly backed up from the main electronic system. Backup tapes were made on August 30, and sent to Houston, Texas. On September 2, within seven hours of receipt, data was available across the entire country and by September 5, additional tapes were uploaded and the system had access to patient progress notes, prescriptions and outpatient clinic orders. A consolidated mail-out pharmacy was set up and utilized all over the country by evacuees who were sent to other states (Brown, et al., 2007). “The VA was able to meet immediate patient care data needs and provide continuity of operations using its electronic health record system and derived data, although VistA was never designed to provide seamless support for large-scale disasters. Moreover, after the Katrina experience, VA staff implemented new methods to ensure uninterrupted availability to VistA data; these new techniques, which combine routine backups and continuous data feeds to remote rehost sites…” (Brown, et al., 2007, p. S138). A different type of medical response was organized by private companies, nonprofit organizations, government, and community pharmacies. KatrinaHealth.org was created to house a database of 7 million prescriptions for 1 million people by September 22 (Brown, et al., 2007). Besides having the capabilities of an 2 electronic health record system backed up and available after a disaster, other lessons learned were to have a disaster and strategy plan developed that contained key details of implementation, recovery locations and plans, risk-reduction measures, detailed step-by-step procedural checklists, and periodic disaster drills (Glandon, Smaltz, & Slovensky, 2014, p. 229). Preparation and planning are the keys to surviving a major disaster. References Brown, S. H., Fischetti, L. F., Graham, G., Bates, J., Lancaster, A. E., McDaniel, D., . . . Kolodner, R. M. (2007). Use of electronic health records in disaster response: The experience of department of veteran affairs after hurricane katrina. American Journal of Public Health, 97(S1), S136-S141. Retrieved October 11, 2015 Glandon, G. L., Smaltz, D. H., & Slovensky, D. J. (2014). Information systems for healthcare management (Eighth ed.). Chicago: Health Administration Press. Most, A. (2015, August 23). Hurricane Katrina by the Numbers: 10 Years Later. Retrieved from Time: http://time.com/4007368/hurricane-katrina-by-the-numbers-10-years-later/ Smith, E., & Macdonald, R. (2006). Managing health information during disasters. Health Information Management Journal, 35(2), 8-13. 3