Organization Development Lecture 12

advertisement

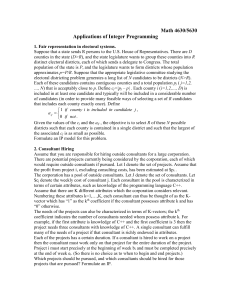

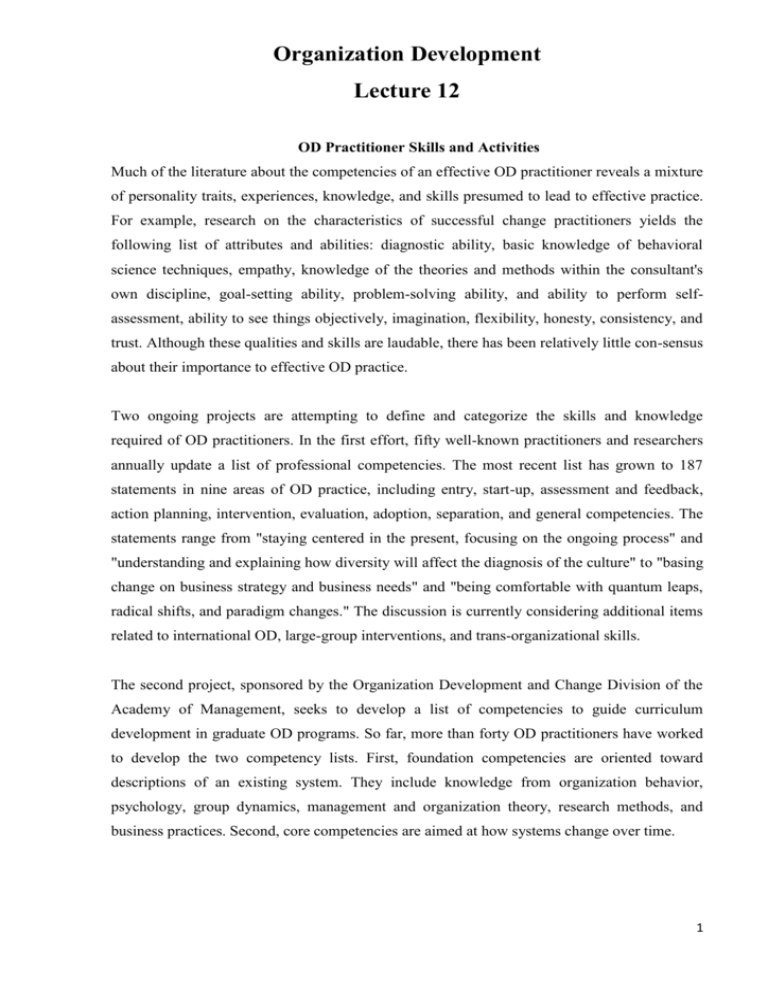

Organization Development Lecture 12 OD Practitioner Skills and Activities Much of the literature about the competencies of an effective OD practitioner reveals a mixture of personality traits, experiences, knowledge, and skills presumed to lead to effective practice. For example, research on the characteristics of successful change practitioners yields the following list of attributes and abilities: diagnostic ability, basic knowledge of behavioral science techniques, empathy, knowledge of the theories and methods within the consultant's own discipline, goal-setting ability, problem-solving ability, and ability to perform selfassessment, ability to see things objectively, imagination, flexibility, honesty, consistency, and trust. Although these qualities and skills are laudable, there has been relatively little con-sensus about their importance to effective OD practice. Two ongoing projects are attempting to define and categorize the skills and knowledge required of OD practitioners. In the first effort, fifty well-known practitioners and researchers annually update a list of professional competencies. The most recent list has grown to 187 statements in nine areas of OD practice, including entry, start-up, assessment and feedback, action planning, intervention, evaluation, adoption, separation, and general competencies. The statements range from "staying centered in the present, focusing on the ongoing process" and "understanding and explaining how diversity will affect the diagnosis of the culture" to "basing change on business strategy and business needs" and "being comfortable with quantum leaps, radical shifts, and paradigm changes." The discussion is currently considering additional items related to international OD, large-group interventions, and trans-organizational skills. The second project, sponsored by the Organization Development and Change Division of the Academy of Management, seeks to develop a list of competencies to guide curriculum development in graduate OD programs. So far, more than forty OD practitioners have worked to develop the two competency lists. First, foundation competencies are oriented toward descriptions of an existing system. They include knowledge from organization behavior, psychology, group dynamics, management and organization theory, research methods, and business practices. Second, core competencies are aimed at how systems change over time. 1 They include knowledge of organization design, organization research, system dynamics, OD history, and theories and models for change; they also involve the skills needed to manage the consulting process, to analyze and diagnose systems, to design and choose interventions, to facilitate processes, to develop clients' capability to manage their own change, and to evaluate organization change. The information in Table.1 applies primarily to people specializing in OD as a profession. For them, possessing the listed knowledge and skills seems reasonable, especially in light of the growing diversity and complexity of interventions in OD. Gaining competence in those areas may take considerable time and effort, and it is questionable whether the other two types of OD practitioners—managers and specialists in related fields—also need that full range of skills and knowledge. It seems more reasonable to suggest, whether they are OD professionals, managers, or related specialists. Those items would constitute the practitioner's basic skills and knowledge. Beyond that background, the three types of OD practitioners likely would differ in areas of concentration. OD professionals would extend their breadth of skills across the remaining categories. Based on the studies available, all OD practitioners should have the following basic skills and knowledge to be effective: 1. Intrapersonal skills. Despite the growing knowledge base and sophistication of the field, organization development is still a human craft. As the primary instrument of diagnosis and change, practitioners often must process complex, ambiguous information and make informed judgments about its relevance to organizational issues. Practitioners must have the personal centering to know their own values, feelings, and purposes as well as the integrity to behave responsibly in a helping relationship with others. Because OD is a highly uncertain process requiring constant adjustment and innovation, practitioners must have active learning skills and a reasonable balance between their rational and emotional sides. Finally, OD practice can be highly stressful and can lead to early burnout, so practitioners need to know how to manage their own stress. 2. Interpersonal skills. Practitioners must create and maintain effective relationships with individuals and groups within the organization and help them gain the competence necessary to solve their own problems. Group dynamics, comparative cultural perspectives, and business functions are considered to be the foundation knowledge, and managing the consulting process and facilitation as core skills. 2 All of these interpersonal competencies promote effective helping relationships. Such relationships start with a grasp of the organization's perspective and require listening to members' perceptions and feelings to understand how they see themselves and the organization. This understanding provides a starting point for joint diagnosis and problem solving. Practitioners must establish trust and rapport with organization members so that they can share pertinent information and work effectively together. This requires being able to converse in members' own language and to give and receive feedback about how the relationship is progressing. To help members learn new skills and behaviors, practitioners must serve as concrete role models of what is expected. They must act in ways that are credible to organization members and provide them with the counseling and coaching necessary to develop and change. Because the helping relationship is jointly determined, practitioners need to be able to negotiate an acceptable role and to manage changing expectations and demands. 3. General consultation skills. OD starts with diagnosing an organization or department to understand its current functioning and to discover areas for further development. OD practitioners need to know how to carry out an effective diagnosis, at least at a rudimentary level. They should know how to engage organization members in diagnosis, how to help them ask the right questions, and how to collect and analyze information. A manager, for example, should be able to work with subordinates to determine jointly the organization's or department's strengths or problems. The manager should know basic diagnostic questions some methods for gathering information, such as interviews or surveys, and some techniques for analyzing it, such as force-field analysis or statistical means and distributions. In addition to diagnosis, OD practitioners should know how to design and execute an intervention. They need to be able to define an action plan and to gain commitment to the program. They also need to know how to tailor the intervention to the situation, using information about how the change is progressing to guide implementation. For example, managers should be able to develop action steps for an intervention with subordinates. They should be able to gain their commitment to the program (usually through participation), sit down with them and assess how it is progressing, and make modifications if necessary. 4. Organization development theory. The last basic tool OD practitioners should have is a general knowledge of organization development. They should have some appreciation for planned change, the ac-tion research model, and contemporary approaches to managing change. 3 They should be familiar with the range of available interventions and the need for evaluating and institutionalizing change programs. Perhaps most important is that OD practitioners should understand their own role in the emerging field of organization development, whether it is as an OD professional, a manager, or a specialist in a related area. The role of the OD practitioner is changing and becoming more complex, Ellen Fagenson and W. Warner Burke found that the most practiced OD skill or activity was team development, whereas the least employed was the integration of technology (see Table 1). The results of this study reinforce what other theorists have also suggested. The OD practitioners of today are no longer just process facilitators, but are expected to know something about strategy, structure, reward systems, corporate culture, leadership, human resource development and the client organization's business. As a result, the role of the OD practitioner today is more challenging and more in the mainstream of the client organization than in the past. Table 1: OD Practitioner Skills and Activities Susan Gebelein lists six key skill areas that are critical to the success of the internal practitioner. These are shown in Figure15. The relative emphasis on each type of skill will depend upon the situation, but all are vital in achieving OD program goals. The skills that focus on the people-oriented nature of the OD practitioner include: • Leadership. Leaders keep members focused on key company values and on opportunities and need for improvement. A leader's job is to recognize when a company is headed in the wrong direction and to get it back on the right track. • Project Management. This means involving all the right people and department to keep the change program on track. • Communication. It is vital to communicate the key values to everyone in the organization. 4 • Problem-Solving. The real challenge is to implement a solution to an organizational problem. Forget about today's problems: focus constantly on the next set of problems. • Interpersonal. The number-one priority is to give everybody in the organization the tools and the confidence to be involved in the change process. This includes facilitating, building relationships, and process skills. • Personal. The confidence to help the organization make tough decisions, introduce new techniques, try something new, and see if it works. Figure 15: Practitioner Skills Profile The OD practitioner's role is to help employees create their own solutions, systems, and concepts. When the practitioner uses the above-listed skills to accomplish these goals, the employees will work hard to make them succeed, because they are the owners of the change programs, Consultant’s Abilities: Ten primary abilities are key to an OD consultant’s effectiveness. Most of these abilities can be learned, but because of individual differences in personality or basic temperament, some of them would be easier for some to learn than for others. 1. The ability to tolerate ambiguity. Every organization is different, and what worked before may not work now; every OD effort starts from scratch, and it is best to enter with few preconceived notions other than with the general characteristics that we know about social systems. 5 2. The ability to influence. Unless the OD consultant enjoys power and has some talent for persuasion, he or she is likely to succeed in only minor ways in OD. 3. The ability to confront difficult issues. Much of OD work consists of exposing issues that organization members are reluctant to face. 4. The ability to support and nurture others. This ability is particularly important in times of conflict and stress; it is also critical just before and during a manager’s first experience with team building. 5. The ability to listen well and empathize. This is especially important during interviews, in conflict situations, and when client stress is high. 6. The ability to recognize one’s feelings and intuition quickly. It is important to be able to distinguish one’s own perceptions from those of the client and also be able to use these feelings and intuitions as interventions when appropriate and timely. 7. The ability to conceptualize. It is necessary to think and express in understandable words certain relationships, such as the cause-and-effect and if-then linkages that exist within the systemic context of the client organization. 8. The ability to discover and mobilize human energy, both within oneself and within the client organization. There is energy in resistance, for example, and the consultant’s interventions are likely to be most effective when they tap existing energy within the organization and provide direction for the productive use of the energy. 9. The ability to teach or to create learning opportunities. This ability should not be reserved for classroom activities but should be utilized on the job, during meetings, and within the mainstream of the overall change effort. 10. The ability to maintain a sense of humor, both on the client’s behalf and to help sustain perspective: Humor can be useful for reducing tension. It is also useful for the consultant to be able to laugh at himself or herself; not taking oneself too seriously is critical for maintaining perspective about an OD effort, especially since nothing ever goes exactly according to plan, even though OD is supposed to be a planned change effort. 6 Role of Organization Development Professionals Position: Position: Organization development professionals have positions that are either internal or external to the organization. Internal consultants are members of the organization and often are located in the human resources department. They may perform the OD role exclusively, or they may combine it with other tasks, such as compensation practices, training, or labor relations. Many large organizations, such as Intel, Merck, Abitibi Consolidated, BHP, Philip Morris, Levi Strauss, Procter & Gamble, Weyerhaeuser; GTE, and Citigroup, have created specialized OD consulting groups. These internal consultants typically have a variety of clients within the organization, serving both line and staff departments. External consultants are not members of the client organization; they typically work for a consulting firm, a university, or themselves. Organizations generally hire external consultants to provide a particular expertise that is unavailable internally and to bring a different and potentially more objective perspective into the organization development process. Table.2 describes the differences between these two roles at each stage of the action research process. During the entry process, internal consultants have clear advantages. They have ready access to and relationships with clients, know the language of the organization, and have insights about the root cause of many of its problems. This allows internal consultants to save time in identifying the organization's culture, informal practices, and sources of power. They have access to a variety of information, including rumors, company reports, and direct observations. In addition, entry is more efficient and congenial, and their pay is not at risk. External consultants, however, have the advantage of being able to select the clients they want to work with according to their own criteria. The contracting phase is less formal for internal consultants and there is less worry about expenses, but there is less choice about whether to complete the assignment. Both types of consultants must address issues of confidentiality, risk project termination (and other negative consequences) by the client, and fill a third-party role. During the diagnosis process, internal consultants already know most organization members and enjoy a basic level of rapport and trust. But external consultants often have higher status than internal consultants, which allows them to probe difficult issues and assess the organization more objectively. 7 In the intervention phase, both types of consultants must rely on valid information, free and informed choice, and internal commitment for their success, However, an internal consultant's strong ties to the organization may make him or her overly cautious particularly when powerful others can affect a career. Internal consultants also may lack certain skills and experience in facilitating organizational change. Inside he may have some small advantages in being able to move around the system and cross key organizational boundaries. Finally, the measures of success and reward differ from those of the external practitioner in the evaluation process. A promising approach to having the advantages of both internal and external OD consultants is to include them both as members of an internal-external consulting team. External consultants can combine their special expertise and objectivity with the inside knowledge and acceptance of internal consultants. The two parties can use complementary consulting skills while sharing the workload and possibly accomplishing more than either would by operating alone. Internal consultants, for example, can provide almost continuous contact with the client, and their external counterparts can provide specialized services periodically, such as two or three days each month. External consultants also can help train their organization partners, thus transferring OD skills and knowledge to the organization. Although little has been written on internal-external consulting teams, recent studies suggest that the effectiveness of such teams depends on members developing strong, supportive, collegial relationships. They need to take time to develop the consulting team; confronting individual differences and establishing appropriate roles and exchanges, member’s need to provide each other with continuous feedback and make a commitment to learning from each other. In the absence of these team-building and learning activities, internal-external consulting teams can be more troublesome and less effective than consultants working alone. 8 The difference between External and Internal Consulting Stage of change External consultant Internal consultant Ready access to Entering Source clients clients Build relationships Ready relationships Knows company Learn company jargon jargon Understands root “presenting problem” challenge causes Time Contracting Time consuming efficient Stressful phase Congenial phase Select project/client according to own Obligated to work with criteria everyone Unpredictable outcome Steady pay Formal documents Informal agreements Must complete projects Can terminate project at will assigned No out-of-pocket Guard against out-of-pocket expenses expenses Information confidential Information can be open or Loss of contract at stake confidential Risk of client retaliation and Maintain third-party role loss of job at state Act as third party, driver (on behalf of client or pair of hands) Meet most organization members for the Diagnosing first time Has relationships with many organization 9 members Prestige determined by job Prestige from being external Build trust quickly rank and client stature Sustain reputation as Confidential data can increase political trustworthy sensitivities over time Data openly shared can reduce political intrigue Intervening Insist on valid information, free and Insist on valid information, informed free and informed choice and choice, and internal commitment internal Confine activities within boundaries of commitmen client t Run interference for client organization across organization al lines to align support Evaluating Rely on repeat business and customer Rely on repeat business, pay referral as raise and promotion as key key measures of project success measures Seldom see long-term results of success Can see change become institutionalized Little recognition for job well don e 10 Marginality: A promising line of research on the professional OD role centers on the issue of marginality. The marginal person is one who successfully straddles the boundary between two or more groups with differing goals, value systems, and behavior patterns. Whereas in the past, the marginal role always was seen as dysfunctional, marginality now is seen in a more positive light. There are many examples of marginal roles in organizations: the salesperson, the buyer, the first-line supervisor, the integrator and the project manager. Evidence is mounting that some people are better at taking marginal roles than are others. Those who are good at it seem to have personal qualities of low dogmatism, neutrality, open-mindedness, objectivity, flexibility, and adaptable information- processing ability. Rather than being upset by conflict, ambiguity, and stress, they thrive on it. Individuals with marginal orientations are more likely than others to develop integrative decisions that bring together and reconcile viewpoints among opposing organizational groups and are more likely to remain neutral in controversial situations. Thus, the research suggests that the marginal role can have positive effects when it is filled by a person with a marginal orientation. Such a person can be more objective and better able to perform successfully in linking, integrative, or conflict-laden roles, There are two other boundaries: the activities boundary and the membership boundary. For both, the OD consultant should operate at the boundary, in a marginal capacity. With respect to change activities, particularly implementation, the consultant must help but not be directly involved. Suppose an off-site team-building session, for a manger and his subordinates, he would help the manager with the design and process of the meeting but would not lead. With respect to membership, the OD consultant is never quite in nor quite out. Although the consultant must be involved, he or she cannot be a member of the client organization. Being a member means that there is vested interest, a relative lack of objectivity. Being totally removed means, he cannot sense, cannot be empathetic, and cannot use his or her feelings. Being marginal means that the consultant becomes involved enough to understand client’s feelings and perceptions yet distant enough to be able to see these feelings and perceptions for what they are. Being marginal is critical for both an external consultant and an internal consultant. The major concern regarding the internal OD practitioner’s role is that he or she can never be a consultant to his or her own group. 11 If the group is an OD department, a member of this department, no matter how skilled, cannot be an affective consultant to it. It is also difficult for an internal OD practitioner to be a consultant to any group that is within the same vertical path or chain of the managerial hierarchy as he or she may be. Since the OD function is often a part of corporate personnel or the human resource function, it would be difficult for the internal OD consultant to play a marginal role in consulting with any of the groups within the corporate function, because the consultant would be a primary organization member of that function. Consulting with marketing, R&D or manufacturing within one’s organization, for example, would be far more feasible and appropriate, since the OD consultant could more easily maintain a marginal role. Figure 16: Use of Consultant’s Versus Client’s Knowledge and Experience With the recent proliferation of OD interventions in the structural, human resource management, and strategy areas that limited definition of the professional OD role has expanded to include the consultant-centered end of the continuum. In many of the newer approaches, the consultant may have to take on a modified role of expert, with the consent and collaboration of organization members. For example, if a consultant and managers were to try to bring about a major structural redesign, managers may not have the appropriate knowledge 12 and expertise to create and manage the change. The consultant's role might be to present the basic concepts and ideas and then to struggle jointly with the managers to select an approach that might be useful to the organization and to decide how it ' might best be implemented. In this situation, the OD professional recommends or prescribes particular changes and is active in planning how to implement them. This expertise, however, is always shared rather than imposed. With the development of new and varied intervention approaches, the OD professional's role needs to be seen as falling along the entire continuum from client-centered to consultantcentered. At times, the consultant will rely mainly on organization members' knowledge and experiences to identify and solve problems. At other times, it will be more appropriate to take on the role of expert, withdrawing from that role as managers gain more knowledge and experience. Emotional Demands: The OD practitioner role is emotionally demanding. Research and practice support the importance of understanding emotions and their impact on the practitioner's effectiveness. The research on emotional intelligence in organizations suggests a set of abilities that can aid OD practitioners in conducting successful change efforts. Emotional intelligence refers to the ability to recognize and express emotions appropriately, to use emotions in thought and decisions, and to regulate emotion in oneself and in others. It is, therefore, a different kind of intelligence from problem-solving ability, engineering aptitude, or the knowledge of concepts. In tandem with traditional knowledge and skill, emotional intelligence affects and supplements rational thought; emotions help prioritize thinking by directing attention to important information not addressed in models and theories. In That sense, some researchers argue that emotional intelligence is as important as cognitive intelligence. Reports from OD practitioners support the importance of emotional intelligence in practice. At each stage of planned change, they must relate to and help organization members adapt to resistance, commitment, and ambiguity. Facing those important and difficult issues raises emotions such as the fear of failure or rejection. As the client and others encounter these kinds of emotions, OD practitioners must have a clear sense of emotional effects, including their own internal emotions. Ambiguity or denial of emotions can lead to inaccurate and untimely interventions. 13 For example, a practitioner who is uncomfortable with conflict may intervene to diffuse conflict because of the discomfort he or she feels, not because the conflict is destructive. In such a case, the practitioner is acting to address a personal need rather than intervening to improve the system's effectiveness. Evidence suggests that emotional intelligence increases with age and experience. In addition, it can be developed through personal growth processes such as sensitivity training, counseling, and therapy. It seems reasonable to suggest that professional OD practitioners dedicate themselves to a long-term regimen of development that includes acquiring both cognitive learning and emotional intelligence. Use of Knowledge and Experience: The professional OD role has been described in terms of a continuum ranging from clientcentered (using the client's knowledge and experience) to consultant-centered (using the consultant's knowledge and experience, as shown in Figure 16), Traditionally, OD consultants have worked at the client-centered end of the continuum. Organization development professionals, relying mainly on sensitivity training, process consultation, and team building, have been expected to remain neutral, refusing to offer expert advice on organizational problems. Rather than contracting to solve specific problems, the consultant has tended to work with organization members to identify problems and potential solutions, to help them study what they are doing now and consider alternative behaviors and solutions, and to help them discover whether, in fact, the consultant and they can learn to do things better. In doing that the OD professional has generally listened and reflected upon members' perceptions and ideas and helped clarify and interpret their communications and behaviors. 14 15