A Taste of Hope Sends Refugees Back to Darfur

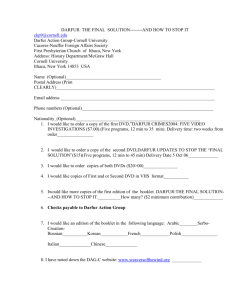

advertisement

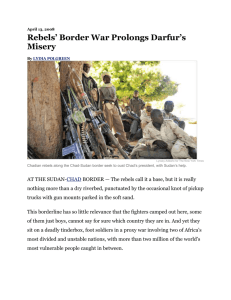

A Taste of Hope Sends Refugees Back to Darfur By Jeffrey Gettleman, The New York Times 26 February 2012 More than 100,000 people in Darfur have left the sprawling camps where they had taken refuge for nearly a decade and headed home to their villages over the past year, the biggest return of displaced people since the war began in 2003 and a sign that one of the world’s most infamous conflicts may have decisively cooled. The millions of civilians who fled into camps, their homes often reduced to nothing more than rings of ash by armed raiders, are among the most haunting legacies of the conflict in Darfur, transforming this rural landscape into a collection of swollen impromptu squatter towns. And while the many thousands going home are only a small fraction of Darfur’s total displaced population, they are doing so voluntarily, United Nations officials say, offering one of the most concrete signs of hope this war-weary region has seen in years. “It’s amazing,” said Dysane Dorani, head of the United Nations peacekeeping mission for the western sector of Darfur. “The people are coming together. It reminds me of Lebanon after the civil war.” If ever there was a ghost town, it was the village of Nyuru, on a windswept hill in western Darfur, where countless people were gunned down by men on horseback or stabbed with crude little daggers when this region of Sudan exploded in bloodshed in 2003. After that, everybody fled, and they stayed away for years. But on a recent morning, thousands of Nyuru’s residents were back on their land doing all the things they used to do, scrubbing clothes, braiding hair, sifting grain and preparing for a joint feast of farmers and nomads. Former victims and former perpetrators would later sit down side by side together, some for the first time since Darfur’s war broke out, sharing plates of macaroni and millet — and even the occasional dance — in a gesture of informal reconciliation. After all the years of international diplomacy, sanctions, billions of dollars spent on peacekeepers and an extremely well-oiled advocacy machine that elevated Darfur into a worldwide cause célèbre, attracting the likes of George Clooney and Mia Farrow, parts of Darfur finally appear to be turning around, for a few reasons. The most obvious is that Sudan recently made peace with Chad, securing a border that used to be crawling with proxy forces and militiamen toting bazookas. Western aid groups are now trying to capitalize on this, partially shifting away from emergency aid and increasing funds for what they call “recovery,” providing brave pioneers with all the essentials they need to go home and stay home, like seeds, wells, plows and workshops to make plows. Even the death of Libya’s dictator, Col. Muammar elQaddafi, has had ripples — good ripples, people here say. Colonel Qaddafi used to supply guns to Darfurian rebels, part of his meddling across this patch of Africa. Now that he is gone, the rebels are weaker, with some more in the mood to negotiate, as evidenced by a recent peace treaty signed by one rebel faction. Of course, all is not well in Darfur. More than two million people remain stuck in internal displacement or refugee camps, and some rebel groups fight on. But people who have been victimized and traumatized are sensing a change in the air and acting on it, risking their lives and the lives of their children to leave the relative safety of the camps to venture back to where loved ones were killed. Abdallah Mohamed Abubakir, a skinny farmer, just brought his family back to Nyuru. “Things aren’t great,” he said, “but they’re getting better.” A quick glance around Nyuru illuminates what he means. The village school may be six sagging grasswalled huts — but it is a new school. The village hospital is one large dusty tent — but it is also new, paid for by an Islamic charity. Not far away are smashed houses and traces of ash on the ground, the footprints of the violence nine years ago, almost as if the land itself was quietly saying: people were killed here, many, many people. But, at the same time, there is a new police station standing on a hill, with a fresh coat of high-gloss blue, and there are no reports of major violence. Until just a few weeks ago, the Abubakirs, like hundreds of thousands of other Darfurians, had been living in Chad. They were essentially serfs, renting a tiny spit of land and barely surviving off it. They fled to Chad in 2003, when nomadic Arab militias sponsored by Sudan’s government — the infamous Janjaweed — rampaged the Darfurian countryside, slaughtering tens of thousands of civilians who belonged to the same ethnic groups as the Darfurian rebels. But in the past few months, word began to trickle back to Chad that the Janjaweed were gone. The Abubakirs — Abdallah and his wife and their two children — decided to pack up and return. “And it’s true,” Mr. Abubakir said. “You can go out to the bushes and collect firewood and nobody bothers you.” He added, “People are coming back every day.” Nancy Lindborg, a top official with the United States Agency for International Development, said, “We’re very optimistic about that area.” A recent agency news release featured Nyuru, under the headline: “Darfur’s Window of Opportunity.” François Reybet-Degat, the current head of the United Nations refugee office in Sudan, said that more than 100,000 people returned home to several different areas of Darfur in 2011, far more than in any year before that. “It’s an early sign of a bigger trend,” he said. “There are still pockets of insecurity, but the general picture is that things are improving.” The United Nations will soon start organizing “go and see” visits for refugees in Chad, he said, to scout out their home villages. But some people may never want to go home. The optimism about the uptick in returnees is checked by the sober realization that Darfur’s sprawling displaced person camps — some virtual cities, with more than 100,000 people — will probably never totally disband. Darfur’s conflict has destroyed not only innumerable lives but also a whole way of life. Many villagers who fled into the camps to avoid getting killed have stayed for nearly a decade and grown used to camp services like schools, clean water, health clinics and cellphone coverage —the very things missing from rural Darfur that planted the seeds for resentment and rebellion in the first place. Many will probably never go back to the harsh village life, and analysts see the giant camps turning into the kind of permanent slums that ring urban centers across Africa, from Kinshasa to Nairobi. Darfur is “a quite different place from 2003,” said Dane Smith, the American senior adviser for Darfur. He cited a telling statistic: In 2003, 18 percent of Darfur’s population lived in urban areas. Now it’s about 50 percent. The peace treaty signed in July between the Sudanese government and one rebel faction, the Liberation and Justice Movement, outlined steps for the compensation of war victims and the prosecution of murderers. But while peace has taken root in some parts of Darfur, justice remains a specter. Many Arabs in Nyuru still call the massacres in 2003 an “accident” and speak of them in the passive voice. “Something happened in the past, but it’s over now,” said Ahmed Ayam Orgas, an Arab leader. It does not feel over for Nyuru’s victims. Down by the river is a brickyard, where thick mud bricks bake in the sun. Nyuru never had a brickyard before. Before the conflict, all the houses were made of straw. “But then the entire village was burned down by one match,” said Adam Hajar Omar, a sheikh. He laughed a bitter, little laugh. “We’ve learned our lesson,” he said.