National Strategy for the Management of Coastal Acid Sulfate Soils

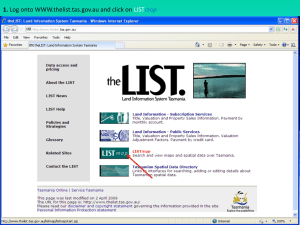

advertisement