FSANZ - Review of Food Labelling Law and Policy

SUBMISSION prepared by Food Standards Australia New Zealand to the

March 2010 Issues Consultation Paper: Food Labelling Law and Policy Review

Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) thanks the Food Labelling Review Committee for the opportunity to submit a response to the Issues Consultation Paper: Food Labelling Law and Policy

Review.

1. Role in the food regulation system

The current standards development process requires FSANZ to meet statutory requirements in the

FSANZ Act 1991and comply with Council of Australian Governments (COAG) Best Practice

Regulation guidelines. This includes using the best available scientific and consumer research evidence to demonstrate that proposed labelling changes will address an existing problem resulting in an overall benefit to the broad community.

1.1 Policy

The framework for food regulation in Australia and New Zealand separates the responsibilities for policy development, standards development and enforcement. Policy development occurs under the aegis of the Food Regulation Ministerial Council (the Ministerial Council) and its subordinate body the Food Regulation Standing Committee (FRSC). While FSANZ has a role in the policy development process, it is restricted to providing technical input. In accordance with this separation of policy from standards development, FSANZ’s role on FRSC is that of an observer rather than a member.

Once the Ministerial Council has arrived at a policy position, this is generally translated into a policy guideline to inform FSANZ’s standards development work.

1.2 Standard development

FSANZ’s primary function in the food regulatory system is that of developing standards. Under the current standards development process, FSANZ is required to consider a number of elements. These include the need to meet statutory requirements under the Food Standards Australia New Zealand Act

(FSANZ) 1991 with respect to three primary objectives, which are identified in the Act as being in descending priority order:

the protection of public health and safety

the provision of adequate information relating to food to enable consumers to make informed choices

the prevention of misleading or deceptive conduct.

The FSANZ Act also requires FSANZ to have regard to the following:

the need for standards to be based on risk analysis using the best available scientific evidence

the promotion of consistency between domestic and international regulations

the desirability of an efficient and internationally competitive food industry

the promotion of fair trading in food

policy guidance provided by the Ministerial Council to FSANZ

There is also a statutory requirement to consult with stakeholders.

Once FSANZ has completed its standards development process, the Board recommends draft

Standards to the Ministerial Council. Ministers have two options: to allow the Standard to go forward for gazettal; or to ask FSANZ to review the draft Standard.

Page 1 of 13

SUBMISSION prepared by Food Standards Australia New Zealand to the

March 2010 Issues Consultation Paper: Food Labelling Law and Policy Review

A review of a proposed Standard or an existing Standard is requested by the Ministerial Council if one or more of the following criteria apply, that is, the Standard:

is not consistent with existing policy guidelines set by the Ministerial Council,

is not consistent with the objectives of the legislation which establishes FSANZ

does not protect public health and safety

does not promote consistency between domestic and international food standards where these are

at variance does not provide adequate information to enable informed choice is difficult to enforce or comply with in both practical or resource terms

places an unreasonable cost burden on industry or consumers.

The Ministerial Council may amend or reject the draft after second review.

FSANZ is also required to consider the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) principles of minimum effective regulation.

1.3 Enforcement

Although FSANZ does not have any actual enforcement powers, it already has a national role in coordinating mandatory recalls. FSANZ has collaborated with the Implementation Sub-Committee

(ISC) to ensure that compliance methods are now developed by the jurisdictions in parallel with standard development.

FSANZ is aware the current system for enforcement gives rise to inconsistent interpretation and difficulties with enforcement of the Code. Work to address this issue is currently being undertaken by

COAG in the context of the Business Regulation Competition Working Group.

1.4 Regulatory Impact Statements and evaluation of benefit to the community

Regulation is an essential part of an efficient economy. As populations have increased and agricultural and food technologies have advanced, the ability of consumers to assess the safety and other attributes of food has decreased. Many people now rely on others to produce, transport, and deliver the majority of their food. For our modern food production and delivery system to work effectively, consumers need to have confidence that the food they buy and consume is safe and that they have appropriate access to information on its attributes.

Protecting the safety and integrity of the food supply has become a basic function of organised society. However, regulation must be carefully designed so as to not have unintended or distortionary effects, such as imposing unnecessary onerous costs on those affected by the regulation, unnecessarily restricting consumer choice or inappropriately restricting competition.

Page 2 of 13

SUBMISSION prepared by Food Standards Australia New Zealand to the

March 2010 Issues Consultation Paper: Food Labelling Law and Policy Review

FSANZ is required to comply with the Council of Australian Government (COAG) Best Practice

Regulation guidelines. The purpose of these guidelines is to maximise the efficiency of new and amended regulations and avoid unnecessary compliance costs and restrictions on competition. The

Office of Best Practice Regulation (OBPR) is responsible for managing compliance with these guidelines. The Food Standards Australia New Zealand Act 1991 also compels FSANZ to take into account all the costs and benefits of a proposal. It should be noted that similar requirements exist at

State/Territory level which apply to the implementation and enforcement of the standards developed by FSANZ.

Where a regulatory proposal has a moderate or high potential impact on business costs, FSANZ must prepare a Regulatory Impact Statement (or a RIS) and undertake associated consultation to satisfy

OBPR requirements. The RIS must specify the problem or issue that has prompted consideration of regulatory action. Information is also provided on the nature and magnitude of the problem and what government actions, if any, have been taken in the past to address the problem. Underlying market failures, regulatory failures and risks are also identified where possible. The market failure that is often identified to justify the need for labelling is the information asymmetry that can exist between food producers and consumers.

Through the RIS, FSANZ must identify both regulatory and non-regulatory solutions and their relative benefits and costs to determine the solution that is likely to have the greatest net benefit to the community. The costs and benefits of all groups in the community are assessed. This includes the costs and benefits to consumers, business and government. The potential net benefits of the various solutions are compared to the status quo.

A number of quantitative approaches are used in developing a RIS. These include:

Risk Analysis

Cost-Benefit Analysis

Cost Effectiveness Analysis

Measuring Business Compliance Costs

Assessing Effects on Competition, and

Social Research.

Qualitative data may also be used where quantification is difficult. Those costs and benefits which cannot be quantified are called ‘intangibles’ and should be presented to the decision maker together with as much descriptive information as possible, so that they can be weighed up alongside the quantifiable variables in the decision making process.

In effect, the requirements placed on regulators are designed to ensure that agencies like FSANZ are focussed on creating regulation that maximises the benefit for the whole community, does not create unnecessary costs and does not unnecessarily restrict competition. This includes deciding not to regulate in some instances. The discipline of compliance with COAG guidelines assist good regulatory outcomes to be achieved. However, as will be discussed below, this can present challenges in determining and collecting appropriate evidence and identifying and applying appropriate analytical techniques. It can also present challenges when food regulatory interventions designed to address complex problems are considered in isolation. Lastly, other challenges arise when the evidence and analysis generates results that conflict with stakeholder perceptions, or which do not deal with values and beliefs in a way that accords with the weighting particular stakeholders place on a given set of values.

Page 3 of 13

SUBMISSION prepared by Food Standards Australia New Zealand to the

March 2010 Issues Consultation Paper: Food Labelling Law and Policy Review

In order to deal with these challenges, FSANZ works closely with the OBPR. In addition, FSANZ is commissioning expert reviews on developing standardised costing models for food safety and on appropriate methods for identifying and analysing ‘intangibles’ in the food regulation context. In addition, FSANZ has developed formal arrangements with its North American counterparts to share information, provide expert input, peer review and to jointly develop new approaches to regulatory impact analysis that better address some of the complex issues facing food regulators.

A Cost Benefit Analysis seeks to establish tangible benefits arising from the regulatory intervention.

Although RISs can include qualitative analyses of benefits, this does require a convincing articulation of these benefits and why they might be expected to occur through the proposed regulatory intervention. For example, an economic value can be determined from reduced health costs flowing from behaviour change. Other possible benefits may be considered including reduced ‘consumer search time’ where consumers may make faster purchasing decisions due to better labelling. Other benefits such as greater awareness, where this awareness does not lead to behaviour change, are even more difficult to value. As mentioned above, FSANZ is commissioning research to improve its understanding of methods which may be able to be used to measure and quantify these difficult to measure potential benefits.

In addition, there may be other benefits from labelling beyond those achieved through direct impacts on consumers. For example, labelling changes may provide incentives to manufacturers to reformulate products.

1.5 Evidence of benefit from labelling

Labelling is seen by many as an effective tool to achieve particular ends. However, it is evident from work undertaken by FSANZ and from the literature, that labelling on its own may fall short of achieving some of the outcomes identified by some stakeholder groups, particularly where changes in consumer behaviour are desired.

Labelling provides an important form of information available to consumers and purchasers at the point of purchase and is able to convey information about food characteristics that would otherwise be unavailable to the consumer, even after consumption (e.g. nutritional information, method of production information). Labelling information may influence consumer behaviour to the extent that the information is of relevance to their particular circumstances. Thus, individuals who seek a lower sodium diet may actively use the nutrition information panel to select appropriate foods; the same piece of information may be totally ignored by an individual with a peanut allergy or a vegetarian seeking food free from animal derived products. Additionally, an individual’s specific food choices are embedded in a broader context, and are influenced by biological, cognitive, economic, social, cultural, geographic and historical factors 1 .

1 Sobal, J. Bisogni, C.A. Devine, C.M. and Jastran, M. (2006) A conceptual model of the food choice process over the life course. In: Shepherd, R. and Raats, M. eds. The psychology of food choice.

CABI, Wallingford, pp

1-18.

Page 4 of 13

Exposure

SUBMISSION prepared by Food Standards Australia New Zealand to the

March 2010 Issues Consultation Paper: Food Labelling Law and Policy Review

In relation to decisions to purchase individual foods, taste, cost and convenience appear to be the major influences in consumer decisions with health and variety impacting to a lesser extent 2 .

Accordingly, attempts to change consumption behaviour through labelling will be limited if they do not address the attributes that consumers seek in food. Furthermore, the broader context in which food choices are made highlights the importance of multi-faceted approaches to encourage behaviour change. Attempts at behaviour change through labelling alone, without complementary actions beyond labelling, are likely to have limited success except for those individuals for whom the change is particularly relevant and who are therefore motivated to change their behaviour.

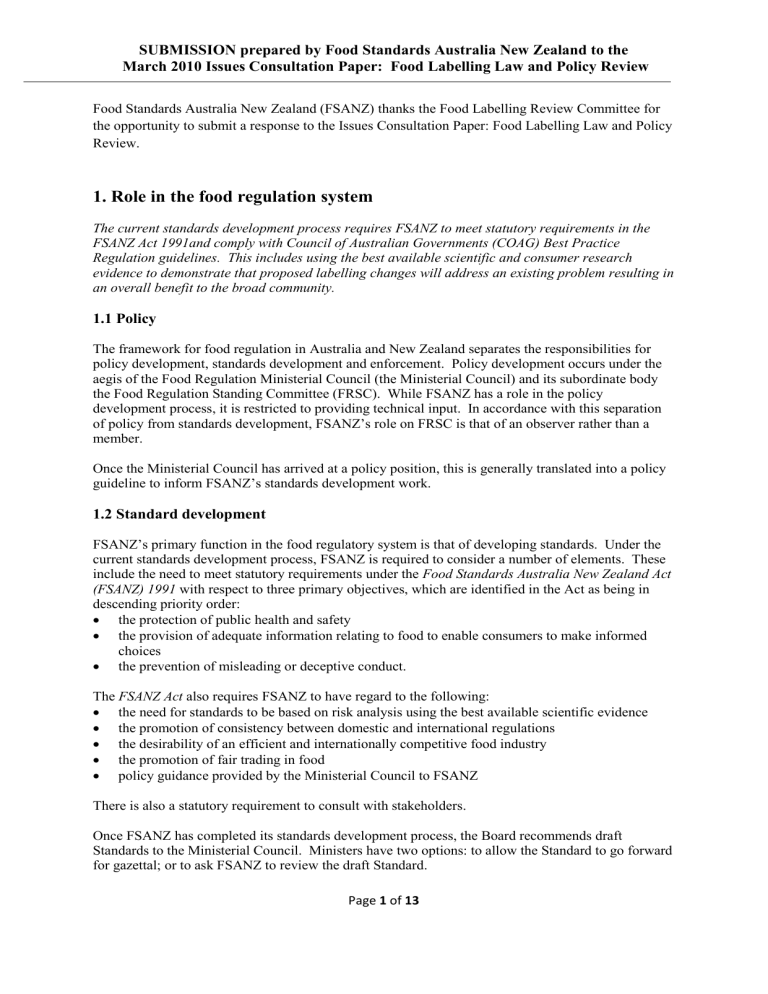

Grunert and Wills 3 and Grunert and others 4 have developed a ‘stages of effect’ model to demonstrate how nutritional information on labels may influence consumers (Figure 1).

Perception

Understanding

Nutritional knowledge

Inferences

Integration

Evaluation

Figure1. Stages of Effect Model.

For the label to have an influence, an individual must be exposed to and perceive the label

Decision information. Influenced by their level of knowledge, an individual may understand the label to varying extents and draw inferences about the product. These inferences based on the label may be integrated with other relevant information to arrive at an overall evaluation and subsequent decision.

While this approach suggests a high degree of cognitive processing in reaching a decision, individuals generally seek to reduce cognitive load and may also use shortcuts or mental heuristics to reach a decision.

2 Drewnowski, A. (2007) Biological, social, cultural, and psychological influences on food choices. Paper delivered to Symposium on Understanding & Influencing Consumer Food Behaviours for Health , ILSI

Southeast Asia Region, Singapore July 18-20.

3 Grunert, K.G. and Wills, J.M. (2007) A review of European research on consumer response to nutrition information on food labels. Journal of Public Health 15: 385-399.

4 Grunert, K.G. Fernández-Celemín, L. Wills, J.M. Storcksdieck genannt Bonsmann, S. and Nureeva, L. (2010)

Use and understanding of nutrition information on food labels in six European countries. Journal of Public

Health (Published online Janurary 10 DOI 10.1007/s10389-009-0307-0).

Page 5 of 13

SUBMISSION prepared by Food Standards Australia New Zealand to the

March 2010 Issues Consultation Paper: Food Labelling Law and Policy Review

The stages of effect model highlights how the stages where the use of a particular label element can be assessed. For example, it is possible to measure the perception (awareness or noticing) of a label; whether the individual understands the label element in the way that is intended; whether they draw any inferences about the product from the label and ultimately the extent to which the label element impacts on any decision. However, as the label information becomes more combined with pre-existing knowledge and values along the stages of effect model, necessarily more aspects influence the process. Isolating the impacts of labelling on ultimate purchase decisions can be problematic. As noted, individual’s food choices are embedded in a broader context and if a specific label element is not of interest to a consumer, they may not become aware of or use that information.

In assessing proposed changes to labelling, FSANZ seeks to understand which label elements impact on which groups of consumers and to what extent.

It can be difficult to obtain evidence of tangible benefit flowing from new labelling requirements.

FSANZ notes the Australian Government’s National Preventative Health Taskforce (NPHT) has identified food labelling as an important part of any obesity prevention strategy. The NPHT pointed out that not only could an effective food labelling system guide consumers to make healthier choices; it could also provide the incentive for manufacturers to improve the nutritional content of their products. The NPHT also suggested that food labelling should help consumers to identify healthier food and drink rather than confusing them further or provide insufficient information about nutrition messages.

1.6 Front-of-pack labelling (FOPL)

FSANZ acknowledges the responsibility of policy development for labelling approaches, such as front-of-pack, resides with the Ministerial Council. However, FSANZ’s analysis to date suggests there is limited evidence to support policy development in the arena beyond the ‘inferences’ stage of the Grunert model, shown in Figure 1. To date, research on different front-of-pack labelling systems used in Australia, the EU and the UK has focused on ‘understandability’ of label information. There has been little research on the effect of FOPL on sustained purchasing behaviour.

The Food Regulation Secretariat Committee has provided FSANZ with the Policy Statement for

Front-of-Pack Labelling, which was endorsed by the Ministerial Council in October 2009. FSANZ anticipates that further comment will be provided following the Review on Food Labelling Law and

Policy.

1.7 Labelling today

Food labels carry a wide range of information for the consumer. Label elements include a name or description of the food, a nutrition information panel to provide compositional information, a statement of ingredients, allergen declarations, date marking, directions for use and storage and food recall information. Consumer awareness and use for the different label elements varies.

While there is a wide literature relating to the impacts of information and labelling on consumers,

FSANZ believes that some of its more recent research is of relevance. The Review Committee has previously been provided with the most recent study that includes data on the use of various label elements reported by Australian and New Zealanders (see pages 46-51 of the Consumer Attitudes

Survey 2007 5 ). The Consumer Attitudes Survey was an Internet implemented survey of a representative sample of Australians aged 14 years and older (n=1202).

5 FSANZ (2008). Consumer Attitudes Survey 2007. A benchmark survey of consumers’ attitudes to food issues. Food Standards Australia New Zealand, ACT.

Page 6 of 13

SUBMISSION prepared by Food Standards Australia New Zealand to the

March 2010 Issues Consultation Paper: Food Labelling Law and Policy Review

Key findings include:

Up to 97% of consumers report referring to food labelling when purchasing products for the first time

Consumers with food or dietary concerns report more frequent use of food labelling when purchasing products for the first time than those without food or dietary concerns

When provided with a list of food label elements, the most commonly reported elements used by consumers were: the best before/use by date (73.1%); amount of fat (61.8%); country of origin

(59.1%); the amount of sugar (56.5%); the ingredients list generally (52.7%) and the amount of saturated fat (50.4%). Other elements were reported by less than 50% of consumers.

“Watching my health/others’ health generally” (63.5%) and “watching my weight/others’ weight generally” (50.1%) were the two most frequent reasons reported by consumers for using food labels.

However, while the survey results above appear to indicate that consumers frequently use labels to influence their food choices when choosing a product for the first time, this does not necessarily mean that consumer food choices could be easily influenced to move towards more ‘desirable’ food choices through label information. Surveys such as the one described are useful in providing general indications about consumers use of labelling, however their generality limits their applicability to specific labelling types and for specific food categories. Data to understand consumers’ responses in specific circumstances is best provided by specifically designed data collection exercises.

2. The role of labelling in meeting public health objectives

The term ‘protection of public health’ is subject to interpretation ranging from protection from food borne hazards to include promotion of longer term public or population health. FSANZ’ remit in the area of labelling to meet public health objectives is also open to interpretation, which in turn leads to a diverse range of that stakeholder expectations of the role and effectiveness of labelling. Many of these expectations about the potential role and effectiveness of labelling are at variance with the evidence.

It is clear from the existing evidence base that labelling may play a role in meeting some public health objectives. However, for many complex, multi-factorial public health problems requiring individuals to change behaviour, this role may be limited in the absence of other complementary initiatives.

FSANZ is aware that a number of stakeholders are of the view that FSANZ should be able to do more to meet public health objectives, particularly though labelling requirements. A stakeholder survey commissioned by FSANZ in 2009 highlighted concern over what role FSANZ should be playing in relation to achieving broader public health objectives as a key issue.

There were several aspects to these concerns and they were often discussed in terms of how FSANZ gives effect to its primary legislative objectives, particularly its highest priority objective, the protection of public health and safety.

The main concerns raised by stakeholders went to:

1.

Whether FSANZ should develop standards with a focus on maintaining or improving public health and safety

2.

Whether FSANZ considers broader public health objectives, or gives adequate weight to this issue in its standards development work, and

3.

A view that FSANZ should be more proactive in addressing broader public health and safety, rather than merely reacting to applications and policy guidance from the Ministerial Council.

Page 7 of 13

SUBMISSION prepared by Food Standards Australia New Zealand to the

March 2010 Issues Consultation Paper: Food Labelling Law and Policy Review

2.1 Protecting versus maintaining public health and safety

Although FSANZ does develop standards that are intended to address public health and safety (for example allergen labelling requirements), it also assesses some applications and proposals against a test of whether they will have a negative impact on public health and safety. Some stakeholders argue this is the wrong test and that instead FSANZ should only permit changes to the food supply or labelling requirements where an improvement to overall public health can be demonstrated.

For example, work on the Health Claims Standard currently under development, has had a focus on ensuring that the new regulatory regime will not result in changes in food consumption which could lead to undesirable consequences such as increased consumption of the risk increasing nutrients saturated fat, salt or sugar. In other words, the approach proposes that health claims will be permitted provided they, amongst other things, do not reduce public health and safety. FSANZ has focussed a significant part of its social research for Health Claims on testing whether the proposed changes might adversely affect consumer behaviour. Some stakeholders have argued that the regulatory focus should, instead, be on ensuring that health claims are not permitted unless they actively improve health outcomes.

There would be circumstances where FSANZ could adopt an approach of permitting new labelling approaches only where this would lead to an improvement in public health outcomes. However, unless the benefits of such an approach outweigh any costs, a proposal to introduce new labelling requirements may not meet OBPR requirements. A net benefit outcome might not be easy to achieve where labelling is considered in isolation given the complexity of many public health problems.

2.2 Addressing broader public health concerns

It is unclear whether those stakeholders that hold a broad public health view consider that FSANZ ignores potential impacts on public health issues (such as obesity) in its standards development work; or whether they consider that the methodologies FSANZ uses to address these issues are inadequate.

Where relevant, FSANZ does assess the potential impacts of individual standards on public health issues such as obesity and dental caries and erosion. The Health Claims work discussed above provides an example. Other recent examples include voluntary and mandatory fortification standards and applications relating to some novel foods such as phytosterols. Each of these applications and proposals considered potential impacts on public health as a key focus and significant effort went into assessing relevant evidence.

However, as described above, it can be difficult to gather and assess this evidence, especially where it relates to potential impacts on human behaviour. FSANZ has taken a number of steps to deal with these challenges including establishing in-house social research expertise; establishing a Social

Science Expert Advisory Group to oversight and peer review this work; establishing a formal working group with key international food regulators on social and consumer research to share information on methodologies and provide peer review mechanisms. In addition, FSANZ designs and obtains social research to inform key standards development work and to augment the often more broadly focussed existing social research literature.

Page 8 of 13

SUBMISSION prepared by Food Standards Australia New Zealand to the

March 2010 Issues Consultation Paper: Food Labelling Law and Policy Review

2.3 Proactive versus reactive approach

During the 2009 stakeholder survey, some stakeholders expressed the view that FSANZ should not wait for policy guidance from the Ministerial Council before raising proposals to address obvious public health problems. However, as discussed earlier, the food regulation framework deliberately separates the policy development function from the standards development work undertaken by

FSANZ. While FSANZ could initiate work to redress public health problems, this work would need to be limited to those areas which do not trespass into the policy arena. Examples of proactive work undertaken by FSANZ include the consumer education material relating to pregnancy health and food; the ‘Choosing the Right Stuff’ shopping guide; and the work with the Food Safety Information

Council providing targeted food safety advice.

3. Provision of information to enable consumers to make informed choices

FSANZ acknowledges the importance of our second order objective in relation to the provision of adequate information to enable consumers to make informed choice. At the same time, FSANZ is obliged to consider it obligations in regard to addressing a defined regulatory problem, the need for minimum effective regulation, consideration of non-regulatory measures and demonstrating an overall benefit to the community.

3.1 Current labelling examples

Current labelling examples of information provided for informed choice include:

Country of Origin Labelling (Standard 1.2.11) – developed in response to public interest and subsequent Policy Guideline

Labelling of genetically modified foods (Standard 1.5.2) – developed in response to public concern and a Ministerial Council request, during the time when Standard 1.5.2 was drafted.

A major challenge in developing standards that have, as their primary purpose, the provision of information to enable consumers to make informed choices, is the cost/benefit test. In 2009, FSANZ rejected an Application to mandate vegetarian labelling on several grounds including that such labelling was unlikely to provide a net public benefit (that is, the costs would be borne by the wider population, when only a small sub-group of consumers would benefit). FSANZ also noted there were differences in the degree to which people choose a vegetarian diet and such labelling would likely fail to benefit all vegetarian consumers.

Another challenge in this area is the potential duplication with provisions covered under other separate Acts of Parliament and the relative effectiveness of food regulatory provisions versus other legislative provisions. For example, terms such as ‘natural’, ‘free range’ and ‘organic’ are captured by provisions in trade practice legislation to prevent misleading or deceptive representations about food and beverages. FSANZ is of the view that trade practice legislation is more appropriate for defining and mandating the use of these terms. Moreover, the penalties under trade practice legislation are greater than under Food Law and are therefore more compelling to food industry.

Page 9 of 13

SUBMISSION prepared by Food Standards Australia New Zealand to the

March 2010 Issues Consultation Paper: Food Labelling Law and Policy Review

It should also be noted that provisions in the Code generally apply to the final food sold or prepared for sale, or food products that are imported. Claims relating to the production processes of food are generally considered to be outside FSANZ’s remit. For example, an organic standard would need to include detailed specification of methods of production, permitted chemicals and testing and certification procedures. FSANZ notes that Standards Australia has since developed a comprehensive organic standard.

3.2 Issues raised by ‘ communities of interest’

There are many specific community group interests unrelated to public health and safety which give rise to calls for food labelling. These interests can include matters of personal choice. There is an overarching question whether it is appropriate for interests held by some groups within the community to be addressed through food labelling regulation, when such regulation will impact the wider consumer community.

Specific community group interests vary widely. Animal welfare labelling and labelling for specific environmental concerns are emerging issues. Examples include labelling to declare palm oil as an ingredient, food miles and carbon foot print labelling and are elicited by smaller population subgroups with a strong interest in the issue.

Vegetarian labelling is an example of a labelling issue that would lead to considerable technical difficulty. That is, there is no international or national consensus on a definition of ‘vegetarian’.

For country of origin labelling, there is a consumer perception that such labelling is a proxy for food safety 6, 7 .

Technology based issues such as nanotechnology and GM food labelling attract a broad degree of public interest and the wide literature on this subject shows that opposition to this technology is driven in part by perceived consumer safety concerns.

FSANZ acknowledges that community information requests are genuine and that there is an evolution of community expectation about food regulation. New labelling standards may well result in costs incurred by the broader community, although the issues themselves may be focused towards a narrower group of consumers. Robust regulatory impact analyses must underpin decisions to impose mandatory labelling.

While the FSANZ’s objectives include ‘the provision of adequate information to enable informed consumer choice’, it is not clear how broadly this objective should be interpreted particularly where matters of personal choice are concerned that are not directly related to food safety and nutrition.

FSANZ notes that where sufficient demand exists, the market can play a role in labelling for consumer information and government intervention may not be necessary. The issue may be more appropriately managed through codes of practice or market driven labelling schemes. Examples include the growing use of palm oil from sustainable sources and RSPO labelling of palm oil, and wider implementation of country of origin labelling for unpackaged foods by some supermarkets.

6 Davies, P. and MacPherson, K. (2010) Country of Origin Labelling: A Synthesis of Research . Prepared for the

UK Food Standards Agency, Available at: http://www.food.gov.uk/science/socsci/surveys/coolsynth

7 Coveney, J. (2007) Food and trust in Australia: Building a picture. Public Health Nutrition 11(3): 237-245.

Page 10 of 13

SUBMISSION prepared by Food Standards Australia New Zealand to the

March 2010 Issues Consultation Paper: Food Labelling Law and Policy Review

New media applications have emerged in recent times, for example e-commerce through the Internet, social networks, iphone applications and bar code scanning to obtain more information than is carried on the food label. The market is already providing different avenues for consumers to access information. These new technologies could be an alternative method to respond to consumer demands for more information.

Non-regulatory solutions can be viable options. For example, an evidence-based FSANZ review of trans fatty acids (TFAs) in the Australia/New Zealand food supply revealed that TFA consumption was low and therefore did not warrant regulatory controls. The dietary intake assessment found more than 90% of Australians and more than 85% of New Zealanders to have TFA intakes below 1% of energy. These figures indicate that Australia and New Zealand continue to meet the World Health

Organisation (WHO) population goal for TFA intake 8 . The Australia New Zealand National

Collaboration on Trans Fats was formed to progress voluntary measures to reduce TFAs in the food supply. The evidence showed this is an effective approach although some specific interest groups were not persuaded. These groups were of the view that labelling was important for those consumers with high TFA intakes, suggesting that regulatory intervention was still warranted.

4. Social and Economic Research

FSANZ’ decisions are required to be evidence-based with an expectation that any regulatory measure proposed is effective in addressing a defined problem. Social and economic research is a fundamental part of the evidence base. In many instances, there is insufficient evidence to support specific labelling measures or the available evidence is not applicable to the Australian and New

Zealand context. FSANZ would value more evidence on how consumers use label information.

The social and economic literature regarding food labelling is spread across a range of disciplines, adopting a number of theoretical and empirical approaches in response to varied issues. While being a broad topic of scholarship, there may be little research that is of direct relevance to particular applications and proposals.

Social and economic research is a fundamental part of the evidence base that underpins the regulatory decisions of FSANZ. Accordingly, FSANZ seeks relevant and robust evidence in developing standards to meet our legislative obligations and to adhere to the COAG Principles and OBPR requirements.

For example, key risk assessment questions about labelling include:

Do individuals read a label element?

Do individuals understand a label element?

Does a label element influence an individual’s evaluations of a product (eg healthiness, intent to purchase)?

Is a label element likely to influence behaviour in the direction desired by the proposed regulatory approach?

The answers to these questions may vary across social, demographic and economic groups.

8 The WHO in 2009 revised its recommendation on TFA intakes, from advising that populations should have

TFA intakes below 1% of total energy on average, to advising that the great majority of the population should have TFA intakes below 1% of total energy

Page 11 of 13

SUBMISSION prepared by Food Standards Australia New Zealand to the

March 2010 Issues Consultation Paper: Food Labelling Law and Policy Review

Social and economic research is also used by FSANZ in adhering to the COAG Principles and OBPR requirements. Thus, where a proposed regulation imposes costs (e.g. mandatory labelling on industry or enforcement costs on jurisdictions), FSANZ seeks social and consumer research that identifies and measures the:

nature and scope of the regulatory problem

impacts that might flow after proposed regulation or non-regulatory options to remedy the identified problem

relative costs and benefits that accrue to different groups

net benefit to society from the recommended option.

FSANZ undertakes reviews of the relevant social sciences and economic literatures to assist in providing the evidence to underpin our decisions. As noted, this may be limited for specific issues and FSANZ will seek to supplement the existing evidence base with additional research. In the case of proposals, FSANZ may design and commission research or, in the case of applications, require applicants to provide specific research. For some types of applications, the social data requirements are specified in the Application Handbook 9 in much the same way as other data requirements for applications (eg toxicological, chemical, and nutritional data).

Available social and economic evidence may have limited applicability to the Australian and New

Zealand context. This may arise from different regulatory systems and food labelling history (e.g nutrition labelling is not mandatory in UK and the required information in the US is different from what is required in Australia and New Zealand). Additionally different social, cultural, demographic and economic characteristics of populations will limit the applicability of international research to

Australian and New Zealand contexts.

The nature and quantity of the social and economic evidence base required for a particular standard will generally be commensurate with the nature and level of risk that is sought to be managed, and the costs and benefits accrued. Thus for routine and minor applications, there will be fewer requirements for social and economic evidence than for larger and complex standards. In the case of very complex and large proposals introducing new labelling provisions, the required social and economic evidence can be extensive and expensive. For example, FSANZ has expended over $A900, 000 on social and economic studies to provide evidence for Proposal P293 – Nutrition, Health and Related Claims.

It is recognised that FSANZ will often rely on imperfect social and economic evidence but this is also the case for other scientific disciplines. It is, however, important that FSANZ uses the best available evidence and informed expert opinion to form its evidence base. This is particularly the case given the strongly held but often opposed views of non-expert stakeholders and the importance of the problems labelling is seen as having a role in resolving.

5. Internet sale of food

Labelling requirements are generally expressed as “the label on a package of food must include...”. It is unclear whether the same mandatory labelling requirements would apply to the advertising of food via the Internet. Internet sales may warrant some provisions in the Food Standards Code.

9 The Application Handbook is available from the FSANZ website at: http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/foodstandards/changingthecode/applicationshandbook.cfm

.

Page 12 of 13

SUBMISSION prepared by Food Standards Australia New Zealand to the

March 2010 Issues Consultation Paper: Food Labelling Law and Policy Review

6. Desirable outcomes from the Food Labelling Law and Policy Review

From FSANZ’s perspective, there are a number of important issues that could be addressed by the

Food Labelling Law and Policy Review. FSANZ would welcome:

An overarching framework for addressing labelling including:

Clarification of the appropriate role for regulatory intervention,

guidance on the appropriate role of labelling in longer term public health matters,

the role of labelling relative as a single intervention or as one of a suite of measures, and

the role of labelling relative to other available measures that might address longer term public health issues.

A national food and nutrition policy may also be helpful in providing guidance to FSANZ in relation to labelling.

FSANZ would also welcome guidance from the Review Committee on matters such as:

The evaluation of quantitative and qualitative evidence when considering RISs and CBAs, recognising that stakeholder expectations vary widely.

The appropriate scope of labelling when considered in the contexts of FSANZ’s remit and the wide range of issues raised by stakeholders, including the broad community.

Page 13 of 13