Coastal ecologically engineered artificial reefs for multiple functions

Coastal ecologically engineered artificial reefs for multiple functions: food, water quality, shoreline stabilization and protection, carbon sequestration, habitat and ecological services

Steven Hall, Biological and Agricultural Engineering, 143 Doran Stadium Dr, LSU AgCenter, Baton Rouge

LA 70803; 225-281-9454; sghall@agcenter.lsu.edu

; Tyler Ortego, Oratechnologies; Mike Turley,

Wayfarer Environmental Technologies; Robert Beine, LSU AgCenter; Jon Risinger, LSU

Submitted for ASBPA 2011, New Orleans LA, October, 2011

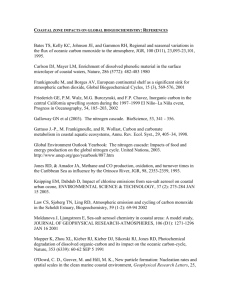

Ecologically engineered artificial reefs have been used to enhance and encourage growth of oysters and other organisms in coastal protection and restoration projects. These can serve multiple functions including food production, water quality enhancement, coastal protection and restoration, carbon sequestration, habitat and ecological services. They can also serve to both mitigate and adapt to climate change, since they actually grow to new ocean levels, while sequestering carbon. These reefs encourage growth of desired organisms and, in areas where regeneration of oyster populations are needed, can in themselves constitute ecological restoration. However, in addition to hosting sessile organisms, these engineered ecosystems, which have high porosities (material may be less than 10% of usual rock breakwaters), also allow juvenile fish to find shelter and may enhance sedimentation or reduce erosion.

Engineering design has focused on optimizing growth of organisms, allowing potential harvest, reducing wave erosion, sequestering carbon for long periods (millennia), and assisting in coastal wetlands restoration. Growth of organisms is enhanced by providing larger amounts of surface area (100-1000% more surface area compared to rock) and including attractants

(agricultural byproducts which release nitrogen compounds), as well as by the geometry.

Harvest could be made from such reefs, and, since they are engineered, they can be made more harvestable. Wave energy is reduced more as growth occurs, so this is a potential negative when first emplaced, but allows enhanced sustainability over time, while carbon is sequestered in shells long term (millennia). Although oysters are animals (and produce CO2), the algae-oyster complex is a net carbon sequestration mechanism, and locks up carbon for very long periods. Ocean acidification is another concern, but oysters have been shown to be minimally impacted by pH changes less than 0.5 pH points, while enhanced levels of carbon dioxide in the water may actually enhance growth of algae, a major food of oysters. In

Louisiana, the current coastal settlement rate of ~1-2 cm/yr allows carbon sequestration that could offset millions of tons annually in large emplacements. Meanwhile, projected sea level rise of 1-2 cm/year is well below growth rates of 3-5 cm/year, meaning these devices can continue to grow and expand once emplaced and maintain a growing living layer in the water column for long periods, reducing the need for fossil-fuel driven maintenance. Finally, coastal wetlands are enhanced both by reduction of erosion and by enhanced habitat for juvenile fish and plant species.

Dr. Hall is Associate Professor and Graduate Chair in Biological and Agricultural

Engineering at Louisiana State University. He has degrees from SUNY Buffalo,

UC Davis and Cornell University (PhD); experience at McGill University (first

Sustainable Agriculture postdoctoral fellow), AuSable Institute, Moog Controls Inc,

Cornell Agricultural Energy Program and LSU; and international experience in

Mexico and Central America, Southern Africa and Europe. He is adjunct faculty at the LSU AgCenter's Aquacultural Research Station, past president of the

Aquacultural Engineering Society, past Secretary of the Institute of Biological Engineering. His focus areas are in coastal bioengineering, resource engineering, aquaculture, biomass conversion and ecological engineering, as well as engineering education, ethics, and interface issues such as science and faith; and environment and health issues. Current foci include

coastal ecological engineering, sustainable agriculture and aquaculture, and he holds several patents. He is a licensed professional engineer in New York and Louisiana.