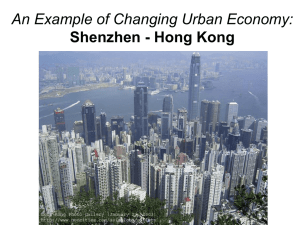

Growth in the number and size of cities

advertisement