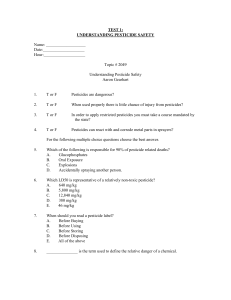

Excerpted and adapted from: Appendix C: ”Safer Pesticide

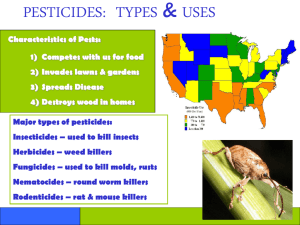

advertisement