Aspects of human language

advertisement

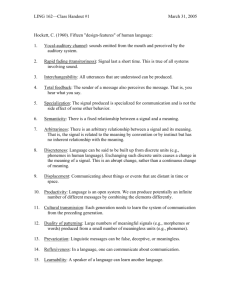

Aspects of human language The following properties of human language have been argued to distinguish it from animal communication: Arbitrariness: There is no rational relationship between a sound or sign and its meaning. (There is nothing intrinsically "housy" about the word "house". i.e. symbolism) Cultural transmission: Language is passed from one language user to the next, consciously or unconsciously. Discreteness: Language is composed of discrete units that are used in combination to create meaning. Displacement: Languages can be used to communicate ideas about things that are not in the immediate vicinity either spatially or temporally, or both. Duality: Language works on two levels at once, a surface level and a semantic (meaningful) level. Metalinguistics: Ability to discuss language itself. Productivity: A finite number of units can be used to create an indefinitely large number of utterances. NOTE: dis·crete adj. 1. Constituting a separate thing; distinct. 2. Consisting of unconnected distinct parts. DISCRETNESS discreteness (n.) A suggested defining property of human language (contrasting with the properties of other semiotic systems), whereby the elements of a discreteness 149 signal can be analysed as having definable boundaries, with no gradation or continuity between them. A system lacking discreteness is said to be ‘continuous’ or non-discrete (see non-discrete grammar). The term is especially used in phonetics and phonology to refer to sounds which have relatively clear-cut boundaries, as defined in acoustic, articulatory or auditory terms. It is evident that speech is a continuous stream of sound, but speakers of a language are able to segment this continuum into a finite number of discrete units, these usually corresponding to the phonemes of the language. The boundaries of these units may correspond to identifiable acoustic or articulatory features, but often they do not. (2008) Cristal, David. A dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics, 6th edition. Blackwell Publishing DISPLACEMENT displacement (n.) A suggested defining property of human language (contrasting with the properties of many other semiotic systems), whereby language can be used to refer to contexts removed from the immediate situation of the speaker (i.e. it can be displaced). For example, if someone says I was afraid, it is not necessary that the speaker still is afraid, whereas animal calls seem generally tied to specific situations, such as danger or hunger, and have nothing comparable to displaced speech (unless this is artificially taught to them, as some experiments with chimpanzees have tried to do). DUALITY duality A property of human language (contrasting with the properties of other semiotic systems), which sees languages as being structurally organized in terms of two abstract levels; also called duality of patterning or duality of structure. At the first, higher level, language is analysed in terms of combinations of (meaningful) units (such as morphemes, words); at another, lower level, it is seen as a sequence of segments which lack any meaning in themselves, but which combine to form units of meaning. These two levels are sometimes referred to as articulations – a ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ articulation respectively. ARBITRARINESS “Arbitrary” here means something “inexplicable in terms of some more general principal”. The most obvious instance of arbitrariness in language has to do with the link between form and meaning, between the signal and the message. There are some exceptional instances in all languages of what is traditionally referred to as “onomatopoeia”, in such cases we may say that there is a non-arbitrary connection between the form and the meaning of such words. However, the vast majority of the words in all languages are nononomatopoeic: the connection between their form and their meaning is arbitrary in that, given the form, it is impossible to predict the meaning, and, given the meaning, it is impossible to predict the form. It is obvious that arbitrariness, in this sense, increases the flexibility and versatility of a communication system in that the extension of the vocabulary is not constrained by the necessity of matching form and meaning. Arbitrariness has both advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, the association of a particular form with a particular meaning must be learned for each vocabulary-unit independently, as a result, a considerable burden is placed upon memory in the language-acquisition process. On the other hand, it makes the systems more flexible and adaptable, but it makes it more difficult to learn. Constrained: confined, limited METALINGUISTICS metalanguage (n.) linguistics, as other sciences, uses this term in the sense of a higher-level language for describing an object of study (or ‘object language’) – in this case the object of study is itself language, the various language samples, intuitions, etc., which constitute our linguistic experience. PRODUCTIVITY The productivity of a language-system is the property which makes possible the construction and interpretation of new signals: i.e. of signals that have not been previously encountered and are not to be found on some list – however large that list might be – of prefabricated signals, to which the user has access. All language-systems enable their users to construct and understand indefinitely many utterances that they have never heard or read before. The fact that children, at a quite early age, are able to produce utterances that they have never heard before is proof that language is not learned solely by means of imitation and memorization. “...within the limits set by the rules of grammar, which are perhaps partly universal and partly specific to particular languages, native speakers of a language are free to act creatively to construct indefinitely many utterance.” (Chomsky) productivity (n.) A general term used in linguistics to refer to the creative capacity of language users to produce and understand an indefinitely large number of sentences. It contrasts particularly with the unproductive communication systems of animals, and in this context is seen by some linguists as one of the design features of human language. The term is also used in a more restricted sense with reference to the use made by a language of a specific feature productivity or pattern. A pattern is productive if it is repeatedly used in language to produce further instances of the same type (e.g. the past-tense affix -ed in English is productive, in that any new verb will be automatically assigned this past-tense form). Nonproductive (or unproductive) patterns lack any such potential; e.g. the change from mouse to mice is not a productive plural formation – new nouns would not adopt it, but would use instead the productive sending pattern. Semi-productive forms are those where there is a limited or occasional creativity, as when a prefix such as un- is sometimes, but not universally, applied to words to form their opposites, e.g. happy unhappy, but not sad *unsad. CULTURAL TRANSMISSION cultural transmission A suggested defining property of human language (contrasting with the properties of many other semiotic systems), whereby the ability to speak a language is transmitted from generation to generation by a process of learning, and not genetically. This is not to deny that children may be born with certain innate predispositions towards language, but it is to emphasize the difference between human language, where environmental learning has such a large role to play, and animal systems of communication, where instinct is more important.