M Gallo Beyond Philanthropy Jan 2012 - ARAN

Beyond Philanthropy: Recognising the Value of Alumni to Benefit

Higher Education Institutions

Maria Gallo, National University of Ireland, Galway – St Angela’s College, Sligo,

Ireland

Abstract

As austerity measures become a reoccurring theme, higher education institutions

(HEIs) worldwide are examining diverse sources of funding, such as philanthropy, as an alternative to State support. This paper argues that building lifelong relationships with alumni offers an HEI with a strategy to yield other residual benefits for the institution, which may also led to philanthropy.

The research offers a deeper understanding of the alumni-academy relationship using

Institutional Advancement (IA) strategies. IA is defined as an approach to building relationship with stakeholders—including alumni—to increase support for an institution. By consulting specialist IA literature, this study develops an alumni relationship building cycle for consideration by institutions. A case study of an Irish university is the vehicle to analyse this paradigm. The empirical evidence shows that by applying IA strategies and building alumni relationships at each stage of the cycle offers the institution positive outcomes ultimately towards advancement.

Introduction

As State funding for higher education decreases, one response by higher education institutions (HEIs) worldwide is to counter this policy by initiating or intensifying private fundraising efforts. For many HEIs outside North America, philanthropy may be a premature option. While private fundraising remains an attractive prospect, this paper argues that before philanthropy, an HEI consider building strategic relationships through Institutional Advancement (IA) processes.

This study examines the extent to which Institutional Advancement practice, including fundraising, is embedded within an institution. In particular, how an HEI builds relationships with graduates (alumni) to form a foundation for wider institutional support, which may include philanthropy at a later stage. Since an HEI initiates the conditions and applies IA strategies for alumni relationships, the onus is on alumni themselves to decide to embrace or ignore this approach from their alma

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 1

mater to develop a lifelong connection. The empirical evidence, through a case study of an HEI, illuminates this alumni relationship building paradigm in practice, showing the potential to transport these ideas to an international higher education environment.

Institutional Advancement

Institutional Advancement is an all-encompassing term for the communications, alumni relations and fundraising strategies within an institution

(Tromble 1998a; Lippincott, 2004). The IA literature outlines practical solutions to initiate, tailor and strengthen relationships with key constitutencies, including alumni. By formalising IA operations, the IA literature offers a step-by-step guide for implementation of IA practice. Many European and most North Amercian HEIs are members of the Council for the Advancement and Support of Education (CASE), the professional association for educational advancement. Through training and resources, CASE reinforces the formulaic nature of IA practice. As a result, IA literature is predominantly a series of resources for ‘advancement professionals’

(Kozobarich, 2000).

IA is virtually an unknown term, sometimes referred to as external relations or development. As a specialist service within an HEI, Institutional Advancement

(IA) is an incremental process to build loyal constituencies for the benefit of an institution. The importance of “friend-raising” before fundraising is increasingly acknowledged (Tromble, 1998b; Weinstein, 2009; Myran et al, 2003; Wagner,

2007), however, there is little empirical data and academic literature to support or critically analyse the stages of advancement. Clark (1998) cites examples of fundraising and alumni relations in what are termed entrepreneurial universities,

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 2

implying that IA practice is as an exception instead of the reality in HEIs worldwide

(Worth, 2002; Albrighton & Thomas, 2001a).

Securing philanthropic funding to realise institutional priorities offers only one outcome to the value of institution-stakeholder relationships. While Alves et al

(2010) identify a number of HEI stakeholders, alumni are only a peripheral reference. This paper contends that since alumni are the only permanent institutional constituency (Webb, 1998) they yield a potential array of benefits for an HEI, worthy of in-depth examination. While the literature on the student experience grows

(Ainley, 2008), the impact of a positive or negative student experience to an alumnus/alumna’s lifetime relationship with their alma mater remains unexplored.

There is criticism that aspects of IA may espouse management practices incongruent to the principles of higher education. For instance, applying marketing strategies treats HEIs as commodities or as a business (Marginson & Considine,

2000; Lynch, 2006; Fairclough, 1993; Jongbloed, 2003) or the rhetoric of students as customers (Bejou, 2005; Browne et al, 1998; Helms & Key, 1994), both of which are an inaccurate reading of this relationship between IA practice and an HEI (Hayes,

2009). Students-turned-alumni have a vested interest in the reputation of their alma mater as it defines their intellectual journey and the value of their qualification.

Moreover, the discourse of the student as a customer ascribes to a short-term studentinstitution relationship, terminated once the educational “product” is accessed or consumed. IA concentrates on building long-term alumni-HEI relationships instead of alumni as only a potential financial return.

CASE is an organisation recognised internationally for developing these three components of IA—communications and marketing; alumni relations and fundraising—as professional practice for the advancement sector. Institutional

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 3

Advancement , as the term suggests, is exactly the purpose the strategy purports: to advance and improve the institution and enable stakeholders to play a key role in this change. This paper draws on IA specialist literature, to deconstruct the stages in which an HEI builds relationships with alumni, creating a paradigm for analysis, with an empirical study to illustrate the paradigm in practice.

Higher Education in Ireland

A brief commentary on Irish higher education is merited. The Irish universities are in a period of transition (Coate and Mac Labhrainn, 2009) continuing from the significant change in the sector over the last twenty years. The recent release of the National Strategy on Higher Education in Ireland (Éire, 2011) may prove to be the impetus to further change within the sector. In the context of IA, the

Report references HEIs seeking ‘additional funding sources’ (Ibid., p. 117) and promoting Irish HEIs internationally (Éire, 2011). IA practice and organisational structures exist in all seven Irish universities. For this paper, suffice to say that IA strategies emerged in Irish HEIs due to the developments in the sector and as a feature of isomorphism, that is, replicating practice from other HEIs in Ireland and worldwide.

Methodology and Context

This research study was conducted in three parts. First a consultation of specialist IA literature, targeted to American IA professionals, is reviewed. This literature is clustered into four categories related to relationship building: from the fundamental institutional structures for alumni relations and broad communication strategies to the development of sophisticated, personalised alumnialma mater interactions. Next, an alumni relationship building cycle is created as a paradigm informed by the four stages identified within the IA literature. Finally, an illustrative

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 4

case study of an Irish university offers explicit examples of the use of IA, demonstrating the stages of the paradigm in practice.

The empirical evidence is drawn from in-depth interviews, documentary analysis and observation, conducted between August 2008 and March 2009. The semi-structured interviews included alumni, students, senior management, strategic administrators and IA-related staff members. With a limited number of IA-related resources within the institution and indeed in the Irish sector, the interviews allowed the discussion to focus exclusively on the evolution of IA practice at the University.

The documents collected for the case study were produced within the University and offered an insight into the carefully controlled image of the institution to the public and key stakeholders. The documents included: annual reports, policy documents, strategic plans, promotional materials, University Foundation documentation, internal newsletters and alumni magazines. Following eight visits to the campus, the field notes from the observation method recorded how IA practice is visible on site and applied at key University events, such as a graduation ceremony and open day for prospective students.

The case study serves to illuminate the object of study—using IA to build alumni relationships— leading to ‘thick description’ (Stake 2005, p. 450).The paradigm generates an input-output-outcome construct for an HEI, synthesising the three parts of the research: IA as the input, the relationship building with alumni as the output and the institutional benefits as the outcome. While the focus is institutional outcomes, students and alumni may also derive benefit from IA activity, although this is not explicitly explored in this study. A single university was studied to provide a manageable and accessible terrain to analyse the progression of alumni relationships and a means to test the paradigm in the field.

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 5

Alumni Relationship Building Cycle

A fundamental aspect of IA is building and managing relationships

(Jacobson, 1986; CASE, 2008; Tromble, 1998b). IA practice is anticipated in

American HEIs: graduates understand and expect to receive alumni magazines, reunion invitations and be asked to make a donation to their alma mater .

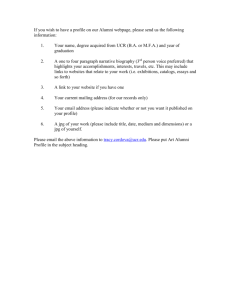

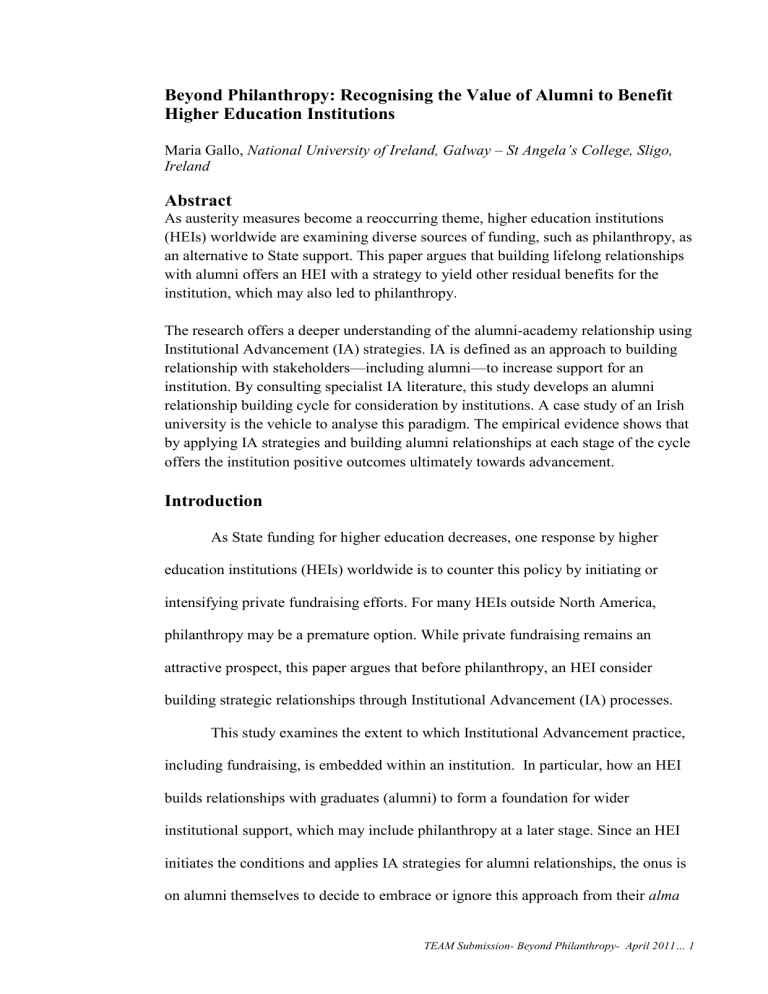

The role of the HEI is to use IA practice to initiate action at each stage of the relationship building cycle: define affiliation, build affinity, foster engagement and secure support. Each stage of this paradigm describes the progress of alumni through the relationship from virtual stranger to close friend. Certain components of IA are most likely to operate at each stage: communication is linked to affinity; alumni relations to engagement; fundraising to support (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The Alumni Relationship Building Cycle Paradigm

Affiliation

Affinity

(Communications)

Support

(Fundraising/

Development)

Engagement

(Alumni Relations)

( ) term in parenthesis indicates the IA component employed at that stage in the cycle

An HEI manages all stages simultaneously, recognising that each alumnus/alumna is at a different stage in the relationship with their alma mater.

An alumnus/alumna progresses in a logical sequence, one stage at a time from affiliation through to support, or disengages from the cycle by no longer connecting with the institution.

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 6

Equally, an alumnus/alumna may re-engage in the cycle, usually by renewing an affinity with the institution.

Affiliation

Alumni, by attending an HEI, have a natural, permanent institutional affiliation. Each alumnus/alumna is identified and categorised in several cohorts such as by graduation year, field of study or student society participation (Simpson, 2001).

The challenge for HEIs at the affiliation stage is to find and record links between alumnus/alumna and institution (Taylor & Onion, 1998; Feudo, 2009; Weerts, 2007).

To manage the thousands of alumni, the IA literature suggests an institution invest in a contact management system to maintain individual alumni records (Taylor

& Onion, 1998; Tromble, 1998b). This database is updated as the alumni community changes: adding new graduates from the student database, identifying deceased graduates and creating links between family members. There is little direct interaction with alumni at this initial stage in the process, instead the institution sets a foundation for tracking alumni affiliations inherited from a student record system

(Buchanan 2000).

The case study university recently acquired an alumni database, recognised by the senior management as an investment in institution’s infrastructure to maintain contact with alumni. Despite the creative efforts to update alumni information, such as updating contact information at the graduation ceremony, hundreds of alumni magazines marked “return to sender” remain stacked in the alumni office, signalling the alumni disconnected from their alma mater. Due to the limited staff resources in the alumni office, instead of searching for these “lost alumni”, the work concentrates instead on alumni with active contact details. While the IA literature encourages

HEIs to invest significantly in IA resources, including systems, staff members and

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 7

programmes, (Harrison et al 1995; Lauer 2010; Tromble 1998a) the findings suggest that the resources at the case study university remain modest, using existing resources in a targeted fashion.

Alumni affiliations are segmented into quantifiable cohort on the university’s database, transferred from the student registration system. The alumni office also attempts to add qualitative information on an individual’s record, such as a note on an alumnus/alumna featured in the media. The anticipated output of this stage is a robust list of alumni including both quantitative and qualitative data, a framework to analyse the demographics and steer the types of alumni activities organised by the institution (Taylor, 2007; Lauer, 2002).

Affinity

Alumni possess an innate connection with their alma mater (Buchanan, 2000;

Button Renz, 2009; Carl, 1986; Tromble, 1998a; Simpson, 2001; Weerts 2007), however, this automatic student-institution affiliation does not necessarily suggest a graduate had a positive institutional experience, and it is argued the student experience also steers the lifelong alumni connection to their alma mater (Button

Renz, 2009; Rissmeyer, 2010).

Communication materials inform, educate and enlighten alumni about their alma mater enabling alumni to gain or renew a sense of association to and allegiance for the institution they attended as students (Button Renz, 2009; Moore, 2010; Hayes,

2009; Sevier, 2008). Roszell (1986) calls this ‘an information stage’ (p. 441), where alumni receive and interpret an HEI’s messages. By segmenting alumni into cohorts in the affiliation stage, the communication becomes targeted and potentially more meaningful to a defined alumni cohort (Tromble, 1998b). The advent of online platforms allows institutions instant access to former students, a vivid

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 8

communication tool (Lippincott, 2004; Taylor, 2007; Sevier, 2008). An HEI’s strong visual identity is described as a crucial component of developing a publicly recognisable brand creating communications with alumni that are effective and consistent with an institution’s values and vision (Albrighton & Thomas, 2001b;

Lauer, 2002; Moore, 2010; Chapleo, 2006; McAlexander et al, 2004).

Affinity is distinct from affiliation as the latter is the focuses on formal, established alumni-institution links while the former describes the alumnus/alumna’s subjective preferences connected to the institution. Precedent (2009) argues that an institution’s attention to alumni affinity should start from student induction, coining the phrase ‘ alumundergraduates,’ (p. 4) combining the word alumni and undergraduate , to recognise and record affiliations of these individuals from the moment they enter campus from sports participation to volunteering with student societies.

Affinity is a qualitative construct; it is difficult to determine whether the communication strategies targeted to alumni are effectively building affinity

(Buchanan, 2000; Lauer, 2002; Sevier, 2008; Moore, 2010). At this stage, the interactions between the institution and alumni are passive and the institution is usually unaware of the sources of affinity for each individual alumnus/alumni, therefore an HEI reports on a broad range of topics, in the hope that one or many references strike an interest in the alumni community (Moore, 2010; Tromble,

1998b; Simpson, 2001).

In the case study, affinity begins by educating students on word “alumni.” and the lifelong relationship this represents. The university promotes a consistent, clear brand identity and marketing strategy to reinforce the institution’s values students, alumni and the community. Frequent use of “we” and “us” in the

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 9

university’s marketing materials, implies that the wider constituency share the institution’s vision. Interactions at the affinity level tend to be one-way—the university outwards to alumni.

The aim of the university’s communications is to steer the alumni perception of the institution. The communication channels combine the past, including historical features and updates on alumni gatherings, with the present and future, reporting on recent direction and achievements of the university. The alumni magazine attempts to appeal to wide alumni demographic, highlighting a variety of seemingly unrelated topics, with the institution as the common denominator. The affiliations from the alumni database lead to targeted contact such as an alumnus/alumna receiving an academic department newsletter from their own graduating field of study.

The case study university communications aim to convey an image of a vibrant, progressive institution to alumni, to conjure up pride, nostalgia and affinity within this constituency for the institution. The intention, or output, is to build on the existing positive student experience referenced in case study findings, translating this initial personal affinity from their past and enable alumni to recognise the value of the institution today to Irish society and on a global scale.

Engagement

The engagement stage begins the two-way alumni-institution relationship building process in earnest. Alumni, with an established affinity, participate in an institution’s alumni relations programmes including: class reunions (Feudo, 2009;

Tromble, 1998b); continuing education (Carl, 1986); affinity services, such as alumni travel events (Buchanan, 2000; Emerson, 1986) and special credit card or group insurance schemes (Taylor & Onion, 1998; Tromble, 1998b); online communities

(Taylor, 2007; CASE, 2008).

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 10

The HEI-organised activities concentrate on attracting an alumni’s selfinterest; alumni participate in events or avail of an alumni service for personal value

(Tromble, 1998a). Engagement is quantifiable, for instance, an HEI is able to track the graduates who attend an honoured year reunion and set targets for future activities. At this stage an alumnus/alumna’s profile is enhanced by adding their involvement in alumni relations activities on their individual database record.

Alumni-to-alumni interactions are centred on social activities, such as meeting with old classmates and opportunities for networking. These events are formalised into an annual cycle of events recognised and anticipated by alumni

(Taylor & Onion, 2009; Feudo, 2002). The initiatives focus on offering a service to encourage alumni participation, yielding little direct benefit for the institution. The cycle may end here with an alumnus/alumni availing of events and services for decades while the HEI relationship remaining static. The institution aims are to nurture these individual relationships over a lifetime to create a large number of loyal, active and committed alumni.

Social activities are also the focus of the engagement stage at the case study university. The alumni events are consistently popular with hundreds of alumni attending the annual reunions and dozens of active regional clubs worldwide. Despite the distance between the alumni and the campus, regional clubs from London to

Beijing tend to be alumni-initiated, both by organising regional events, and also in establishing and maintaining the network, consistent with IA literature (Feudo, 2009;

Taylor & Onion, 2009; Simpson, 2001). Participation in special interest alumni groups, such as the media alumni network or mountaineering alumni club, identify a constituency with a clear affinity and personal motivation to “keep in touch” with other alumni who share similar interests. Armstrong (2002) describes the work of

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 11

clubs such as these as: ‘local homes away from home’ (p. 18), enabling the university to broaden a loyal constituency based on a specialist interest or common location. This activity is meticulously recorded on the database to create enhanced individual alumni profiles. The leap from alumni informing themselves about the university to involving themselves in university initiatives is significant, a result of applying IA strategies as an input to achieve an active alumni base as an output, motivated primarily by alumni personal gain.

Support

Webb (1993) describes alumni support as a ‘lifetime of service’ (p. 303). By donating time, expertise or money, alumni are described as the most valuable resource for an HEI (Tromble, 1998a). Support is the altruistic stage: the institution yields the ultimate benefit from the relationship. Even in IA literature, support is often synonymous with alumni giving donations (Smith, 2001; Sun et al, 2007;

Worth, 2002), however the breadth of service to HEIs by alumni includes:

acting as an institution’s advocate (Portera, 2002; Webb 1998);

offering advice, including as a representative in institutional governance or an alumni association (Turanchik, 2002; Clouse Dolbert, 2002);

participating in student recruitment and acting as an institutional ambassador

(Button Renz, 2009;Weerts et al, 2007);

providing student support (Button Renz, 2009; Jablonski, 1999; Feudo, 2009;

Chewning, 2000), such as offering work placements or employment to students or new graduates.

This stage matches alumnus/alumna’s interests and motivations to an institution’s needs.

Fundraising from alumni is a strategic craft, based on the established relationship with the institution recorded and analysed through individual alumni records. It is a set of factors gathered from alumni records (Taylor, 2007; Belfield and Benny, 2000; Harrison, 1995; Pearson, 1999; Lindahl and Winship, 1992) combined with an alumnus/alumna’s own warmth towards the HEI (Smith, 2001;

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 12

Sun et al, 2007) gained through the affinity and engagement stages that demonstrates a propensity for giving. Ignoring the importance of a relationship first may damage the potential for both donations and wider alumni service in the future.

This altruism also offers returns for the alumnus/alumna, such as contributing to the value of their qualification, gaining new experience and networking (Muller,

1986; Worth, 2002). These supporters legitimise the institution to others—alumni, students, prospective students and the general public—showing these individuals with their involvement are committed to the institution by dedicating time or money.

The support stage is not the end of the process. Ideally, as the cycle continues as the institution changes, improves and identifies new priorities. The cohorts of alumni are continually informed on these renewed advancements, with the opportunity to gain new affinity, engagement and support to benefit the institution.

The case study findings confirm that in the culture for giving in Ireland is not comparable to the United States or even the UK. The university is slowly emerging and building more sophisticated systems of development, similar to international IA practice. The university foundation prepares its major gift prospecting strategy and stewardship planning to be both familiar to American donors consistent with international practice (Worth, 2002; Taylor, 2007; Lauer, 2002) while still attracting a newer Irish philanthropist or alumni-donor. The university foundation influences the university’s list of capital project and priorities, as part of university fundraising campaign, to ensure the areas appeal to prospective donors while involving both senior management and volunteers , university donors themselves, in making the

“ask” to other major donors, a standard practice noted by Dellandrea and Sedra

(2002).

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 13

The support stage at this Irish university goes beyond philanthropy involving extensive alumni service, such as through an alumni-student mentorship programme, alumni representation on the governing body, alumni-run companies offering career options for recent graduates. As the institution adapts to the changes in the higher education climate, the support stage enables the university to improve and expand the institution through strategic initiatives and donations. From the institution’s perspective, the ultimate output to the using IA at the support stage is to anchor participation by alumni to support the institution to assist in increasing enrolment by participating in regional recruitment activity and supporting students through their university experience while also targeting alumni with the means to fund university priorities not supported by the State. Both aspects of alumni support hold merit and value towards expanding and enhancing the university.

Analysis of Cycle

IA practice as an HEI input

, offers ‘communication, service and opportunity’

(Tromble 1998b, p. 229) to alumni. The participation by alumni in IA activity as the output is the progression towards the outcome of change and advancement of the institution. The strength of the alumni-university bond is determined by its breadth and depth of the relationships formed. The role of IA at each stage is to construct a lifelong relationship between alumni and the HEI . The case study suggests that the majority of alumni are still at the affinity stage, moving steadily towards engagement by participating in alumni events, with an indication of altruistic service, based on identified needs of the university. The four stages of the relationship building cycle is an incremental progression for alumni as individuals, and also a progression of outcomes for the institution.

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 14

Outcomes of Alumni Relationships

The design of the relationship building paradigm is such that the outputs, described as two extremes on a spectrum, allows for a progression to outcomes for the HEI’s benefit and to the next stage of the cycle. IA is the catalyst to enable individuals or cohorts of alumni to move through the cycle (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Outcomes mapped on the IA Alumni Relationship Building Cycle

Affiliation

Expand the quantity of alumni

Outcome of Support:

Towards the enhancement and benefit to the institutional priorities

Strategic change

Preserve quality of alumni

Outcome of

Affiliation:

Informed critical

mass of alumni

Affinity

Building on nostalgia

Dynamic change

Support

Building new affinity

Outcome of Affinity:

Creating loyal and informal ambassadors

Outcome of Engagement:

Captive audience of advocates; alumni value the institution and legitimise it with their action

Engagement

Understand and sustain motivations of alumni

At the affiliation stage, alumni are first considered as a quantitative construct, defined as cohorts of graduates from a particular year or in a particular field of study.

As the case study shows, the interest in increasing student enrolment and through

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 15

programmes of student support, retaining students in the institution maximises the size of this cohort as it moves towards graduation. At this initial stage, the HEI aims to create a critical mass of alumni, by gathering accurate data on alumni to initiate the relationship building process. Through education of students on their life after graduation, it is hoped as alumni there is an understanding of why the institution wishes to “keep in touch.” This preserves the quality of the alumni cohort as informed group open to this lifelong relationship.

At the affinity stage, it is implicit that alumni possess nostalgia from their positive student experience. The role of IA at the affinity stage is to build on this nostalgia to progress alumni towards new thinking about the institution and harness this knowledge towards enticing alumni to take an active part in the institution.

Through IA communications, the outcome of the affinity stage is to create informal institutional ambassadors with loyalty and pride in the institution.

As alumni enter the engagement stage of the cycle, they opt for personally advantageous activities. The IA strategies test an alumnus/alumna’s comfort zone by suggesting other ways of engaging in the institution, based on known affinity and past participation. As alumni recognise the personal value in active participation in their alma mater, the institution gains the benefit of a group of alumni first motivated by their own interest to an outcome of creating informed advocates who legitimise the institution in public through their engagement. Alumni engagement is the gateway to altruism, identifying prospective donors and volunteers.

The support stage brings about the most fundamental change in an institution.

By “giving back” to their alma mater , the support stage challenges alumni to channel their interest, affinity and advocacy towards the institution’s development. An HEI encourages dynamic change through alumni volunteering in priority areas, such as in

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 16

recruitment to increase enrolment, for instance. Fundraising is a key tenet of IA and is an input device not an output or outcome, and the output from an alumni donation is the impact of this funding to strategic change of the institution and fundamentally realise the HEIs priorities, such as capital projects or new programmes. While a donation is a way for alumni to show their support to their alma mater, alumni are also involved in assisting to other HEI priorities. For example, involvement in alumni-student mentoring contributes to student retention while alumni participating in student recruitment to increase enrolment help to realise HEI aims and this participation is a solid testimonial of alumni commitment and belief in the desire to improve their alma mater . Thus, investment in a comprehensive alumni relationship building strategy is beyond philanthropy, and, if executed strategically using IA practice, yields significant dividends.

Conclusion

The interest and emphasis to attracting diverse sources of funding, continues to exercise higher education systems worldwide. With many European HEIs funded almost entirely by the State, the role of higher education is to serve a public good and the State policy interests, such as an economic or social inclusion agenda. Autonomy from State control creates lively debates in the academy that become even livelier with the addition of philanthropy; the HEI is left potentially serving the interests of both the State and the private donor, with both influence the steering of an institution’s priorities, leading to other ethical contentions (Speck, 2010). Building loyal constituencies through IA is a response to this conundrum and HEIs need to consider further investment in institutional advancement resources and structures

(European Commission, 2007; Weerts et al, 2007) while recognising the value of

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 17

integrating IA in HEI senior leadership roles (Murphy, 1997; Portera, 2002; Speck

2010; Hodson 2010).

This paper presents a critical analysis of how Institutional Advancement as a strategy, practice and ethos is employed to consider to an alumni-academy relationship as an antecedent and in addition to philanthropy. This study organises the formulaic nature of IA practice into a paradigm with relationships as its key means towards institution’s advancement success. This is an opportunity to deconstruct the IA process and reconstruct it into a paradigm, open for wider debate and extended study in various HEI contexts.

IA, as described in the case study, resembles the systems, structures and practice from the IA literature and in other HEIs. The evidence shows IA emerged as a response to the impact of the higher education climate on the institution: from competition in the student market to the pressure for the diversification of funding.

By adopting IA practice, the university is forging a strong partnership with the alumni to respond to the pressures in the sector.

The case study suggests that an alma mater leaves an indelible mark on an alumnus/alumni both in the cognitive domain with knowledge, skills and critical thinking and in the affective domain with nostalgia, loyalty and fond memories.

Alumni can be cynical of a HEI’s attempt to outreach to them, through reunions, services and other opportunities, afraid this attention has an automatic correlation with asking for a donation. Harrison et al (1995) describe a typical scenario in

American HEIs, reaffirming this common assertion: ‘The newly minted graduate has scarcely had time to frame the new diploma before the first letter of solicitation arrives from the alumni office’ (p. 397). If an HEI adopts a model of building lifelong alumni relationships, instead of focusing on fundraising, there is potential to

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 18

gain wider, meaningful benefits from the alumni constituency. By educating students, alumni and the HEI itself, the benefits to an incremental approach to IA practice can become embedded with an institution’s values and management practice.

Alumni represent their alma mater , both consciously and unconsciously, through the contribution that they make to society. IA performs both a responsive and proactive function to enable an HEI to build relationships with their wider alumni community. By becoming increasingly active in Institutional Advancement practice, an HEI, like a parent, nurtures alumni towards the ultimate advancement of the institution.

References

Ainley, P. (2008). The varieties of student experience - an open research question and some ways to answer it.

Studies in Higher Education , 33(5), 615-624.

Albrighton, F. and Thomas J. (2001a). What is External Relations for?

In:

Albrighton, F. and Thomas, J. (Eds.), Managing External Relations. Buckingham:

Open University Press, 1-7.

Albrighton, F. and Thomas J. (2001b). A Rose by any other Name: Brand

Management and Visual Identity.

In: Albrighton, F. and Thomas, J. (Eds.), Managing

External Relations. Buckingham: Open University Press, 8-19.

Alves, H., Mainardes, E.W. and Raposo, M.(2010) A Relationship Approach to

Higher Education Institution Stakeholder Management. Tertiary Education and

Management , 16(3), 159 - 181.

Armstrong, N. (2002). Measuring the Success of Alumni Clubs.

In: Feudo, J.A. and

Clifford, P.J. (Eds.), Alumni Clubs and Chapters . Washington: CASE,18-26.

Bejou, D. (2005). Treating Students like Customers. BizEd, March/April.

Belfield, C.R. and Beney, A.P. (2000). What determines alumni generousity?

Evidence for the UK. Education Economics, 18, 65-80.

Browne, B., Kaldenberg, D. and Browne, W. (1998). Satisfaction with Business

Education: A Comparison of Business Students and Their Parents. Journal of

Marketing for Higher Education , 9(1), 39-52.

Buchanan, P. (2000).

Handbook of Institutional Advancement . 3 rd

Edition.

Washington: CASE.

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 19

Button Renz, A. (2010). How to Build the Bridge between Students and Alumni.

In:

Feudo, J.A. (Ed.),

Alumni Relations: A Newcomer’s Guide to Success.

2 nd

Edition.

Washington: CASE, 123-129.

Carl, L. (1986). Strengthening Alumni Ties Through Continuing Education.

In:

Rowland, A. W., (Ed.), Handbook of Institutional Advancement . 2nd ed. London:

Jossey Bass Publishers, 426-439.

Chapleo, C. (2006). Is Communications a Strategic Activity in UK Education?

International Journal of Educational Advancement. 6(4), 306-314.

Chewning, P.C. (2000). Student Advancement Programs.

In: Buchanan, P.M.

Handbook of Institutional Advancement.

3 rd

Edition.

Washington: CASE, 255-258.

Clark, B. R. (1998). Creating Entrepreneurial Universities: Organizational

Pathways of Transformation . Oxford: Elsevier Science Ltd.

Clouse Dolbert, S. (2002). ‘Future Trends in Alumni Relations.’ 16 th

Australian

International Education Conference, Hobart, 30 th Septebmer to 4 th October 2002.

[Accessed online: http://www.aiec.idp.com/pdf/ClouseDolbert_p.pdf 14 th

May

2010].

Coate, K. and Mac Labhrainn, I. (2009). Irish Higher Education and the Knowledge

Economy.

In: Huisman, J. (Ed.).

International Perspectives on the Governance of

Higher Education.

London: Routledge, 198-216.

Council for the Advancement and Support of Education (CASE) (2008). Institutional

Advancement Definition. CASE Web site. Available from: www.case.org/About_CASE/About_Advancement.html [Accessed 24 April 2008].

Dellandrea, J. S. and Sedra, A. S. (2002). Academic Planning as the Foundation for

Advancement.

In: Worth, M.J., (Ed.), New Strategies for Educational Fund Raising.

Westport CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 56-64.

Éire. (2011).

The National Strategy for Higher Education. Dublin: Stationery Office.

Emerson, R. (1986). Designing Auxiliary Programs and Services.

In: Rowland,

A.W., (Ed.), Handbook of Institutional Advancement , 2 nd

edition. London: Jossey

Bass Publishers, 469-479.

European Commission, Director General for Research (2007). Engaging

Philanthrophy for University Research- Fundraising by Universities from

Philanthropic Sources: Developing Partnerships between Universities and Private

Donors . Brussels: EU Commission.

Fairclough, N. (1993). Critical Discourse Analysis and the Marketisation of Public

Discourse: The Universities. Discourse & Society, 4(2), 133-168.

Feudo, J.A. (ed.). (2009). Alumni Relations: A Newcomer’s Guide to Success.

2 nd

Edition. Washington: CASE.

Jacobson, H.K. (1986). Skills and Criteria for Managerial Effectiveness. In:

Rowland, A. W., (Ed.) Handbook of Institutional Advancement , 2nd edition. London:

Jossey Bass Publishers.

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 20

Harrison, W.B. (1995). College relations and fund-raising expenditures: Influencing the probability of alumni giving to higher education. Economics of Education

Review. 14, 73-84.

Harrison, W.B., Mitchell, S.K. and Peterson, S.P. (1995). Alumni Donations and

Colleges' Development Expenditures: Does Spending Matter? American Journal of

Economics and Sociology , 54(4), 397-412.

Hayes, T. (2009). Marketing Colleges and Universities: A Services Approach.

Washington: CASE.

Helms, S. and Key, C. (1994). Are Students More Than Customers in the

Classroom? Quality Progress , 27(9), 97-99.

Hodson, J. (2010). Leading the way: The role of presidents and academic deans in fundraising. New Directions for Higher Education , 149, 39-49.

Jablonski, M.R. (1999). Collaborations between Student Affairs and Alumni

Relations.

In: Feudo, J.A.

(Ed.).

Alumni Relations: A Newcomer’s Guide to Success.

Washington: CASE, 101 – 106.

Jongbloed, B. (2003). Marketisation in Higher Education, Clark’s Triangle and the

Essential Ingredients of Markets. Higher Education Quarterly, 57(2),110-135.

Kozobarich, J.L. (2000). Institutional Advancement. In: Johnsrud, L. K. and Rosser,

V.J., (Eds.). Understanding the Work and Career Paths of Midlevel Administrators:

New Directions for Higher Education.

San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 25-34.

Lippincott, J. (2004). Advancing Advancement: A CASE White Paper. In: Network of California Community College Foundations Conference, 1 October 2004,

California, USA. Available from: www.case.org/files/Newsroom/PDF/NCCF

WhitePaper.pdf [Accessed 26 April 2008].

Lauer, L.D. (2002). Competing for Students, Money, and Reputation: Marketing the

Academy in the 21st Century. Washington: CASE.

Lauer, L.D. (2010). Learning to Love the Politics: How to Develop Institutional

Support for Advancement. Washington: CASE.

Lindahl, W.E. and Winship, C. (1992). Predictive models for annual fundraising and major gift fundraising. Nonprofit Management and Leadership. 3, 3-64.

Lynch, K. (2006). Neo-liberalism and Marketisation: the implications for Higher

Education. European Educational Research Journal. 5(1),1-17.

Marginson, S. and Considine, M. (2000). The Enterprise University: Power,

Governance and Reinvention in Australia.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McAlexander, J.H., Koenig, H.F. and Schouten, J.W. (2006). Building Relationships of Brand Community in Higher Education: A Strategic Framework for University

Advancement. International Journal of Educational Advancement. 6(2),107-118.

Moore, R.M. (2010). The Real U: Building Brands that Resonate with Students,

Faculty, Staff and Donors.

Washington: CASE

.

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 21

Muller, S. (1986). Prologue: The Definition and Philosophy of Institutional

Advancement.

In: Rowland, A.W., (Ed.) Handbook of Institutional Advancement , 2 nd edition. London: Jossey Bass Publishers, 1-12.

Murphy, M. K., (Ed.) (1997). The Advancement President and the Academy: Profiles in Institutional Leadership . Phoenix: Oryx Press.

Myran, G., Baker III, G.A., Simone, B and T. Zeiss (2003). Leadership Strategies for

Community College Executives. Washington: American Association of Community

Colleges.

Pearson, J. (1999). Comprehensive research on alumni relationships: Four year of market research at Stanford University. New Directions for Institutional Research.

101, 5-21.

Portera, M. (2002).

Alumni Clubs and Chapters, A President’s Perspective.

In:

Feudo, J.A. and Clifford, P.J. (Eds.) Alumni Clubs and Chapters . Washington:

CASE, 1-5.

Precedent. (2009). Alumdergraduates: Aligning the alumni and student experience online. London: Precedent.

Rissmeyer, P. A. (2010). Student affairs and alumni relations. New Directions for

Student Services , 130, 19–29.

Roszell, S.W. (1986). Alumni Chapter and Constituent Organization.

In: Rowland,

A.W., (Ed.) Handbook of Institutional Advancement . 2 nd

edition. London: Jossey

Bass Publishers, 440-449.

Sevier, R.A. (2008). Building Brand Momentum: Strategies for Achieving Critical

Mass. Washington: CASE.

Simpson, R. (2001). What are Friends For?: Alumni Relations.

In: Albrighton, F. and Thomas, J. (Eds.). Managing External Relations . Buckingham: Open University

Press, 97-107.

Smith, E. (2001). Money, Money, Money: Managing the fundraising process.

In:

Albrighton, F. and Thomas, J., (Eds.). Managing External Relations. Buckingham:

Open University Press, 108-120.

Speck, B. W. (2010). The growing role of private giving in financing the modern university. New Directions for Higher Education , 149, 7-16.

Stake, R.E. (2005). Qualitative Case Studies.

In: Denzin, N.K. and Lincoln, Y.S.,

(Eds.) The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3 rd edition . London: Sage

Publications.

Sun, X., Hoffman, S.C. and Grady, M.L. (2007). A Multivariate Causal Model of

Alumni Giving: Implications for Alumni Fundraisers. International Journal of

Educational Advancement , 7(4), 307-332.

Taylor, G. and Onion, C. (1998). Alumni Relations: Launching Your Program.

Washington: CASE.

Taylor, J. (2007). Advancement Services: A Foundation for Fund Raising. 2 nd

Edition. Washington: CASE.

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 22

Tromble, W.W. (1998a). Excellence in Advancement: Applications for Higher

Education and Nonprofit Organizations . Maryland: An Aspen Publishers.

Tromble, W.W. (1998b). The Function of the Alumni Office, In: Tromble, W.W.

Excellence in Advancement: Applications for Higher Education and Nonprofit

Organizations . Maryland: An Aspen Publishers.

Turanchik, B. (2002). So you want to start an alumni club? Strategic Planning for

Clubs and Chapters.

In: Feudo, J.A. and Clifford, P.J. (Eds.) Alumni Clubs and

Chapters . Washington: CASE, 6-12.

Wagner, L. (2007) Achieving Success in a Fundraising Programme.

In: Conraths, B. and Trusso, B. Managing the University Community: Exploring Good Practice.

Brussels: European Universities Association, 99-100.

Webb, C.H. (1998). The Alumni Movement: A History of Success.

In: Tromble, W.W.

(Ed.) Excellence in Advancement: Applications for Higher Education and Nonprofit

Organizations . Maryland: An Aspen Publishers.

Webb, C.H. (1993). The role of alumni affairs in fund raising.

In; Worth, M.J, (Ed.)

Educational Fund Raising: Principles and Practice . Phoenix: Oryx Press.

Weerts, D.J. (2007). Toward an Engagement Model of Institutional Advancement at

Public Colleges and Universities. International Journal of Educational

Advancement , 7(2), 79-103.

Weerts, D.J. and Ronca, J.M. (2007). Profiles of Supportive Alumni: Donors,

Volunteers, and Those Who “Do It All.”

International Journal of Educational

Advancement, 7(1), 20-34.

Weinstein, S. (2009). The Complete Guide to Fundraising. 3 rd

Edition.

New Jersey:

John Wiley & Sons.

Worth, M.J., (Ed.) (2002). New Strategies for Educational Fund Raising . Westport

Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group.

TEAM Submission- Beyond Philanthropy- April 2011… 23