Admissions of Failure - University of Nottingham

advertisement

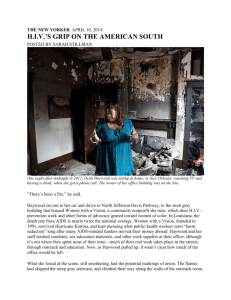

Admissions of failure In this copy of the article, general academic words, from the Academic Word List, are highlighted in bold. It is important that you understand these words and can use them. Study the words in bold carefully. Learn them. British universities must give more language support to their foreign students, argues Rebecca Hughes Thursday January 22, 2004 The Guardian The number of international students in British Higher Education (HE) has risen dramatically over the past 20 years, and has accelerated sharply since 1997 - up by around a third, with more than 30,000 more students being accepted into the system by 2002. Because of this, seismic changes have been taking place in some areas of HE. On certain courses (computer science and IT, business, masters in ELT, some law and politics courses, and foundation courses) international students regularly outnumber "home" students. Some of the consequences of this massive shift are obvious - a sometimes refreshingly hard-working set of students and much needed hard cash for underfunded institutions. However, there are some unintended consequences, and institutions need to think about them at an early stage when they are building a strategy for international recruitment. First, the injection of perhaps a 100 different nationalities into an institution presents quite a radical challenge to assumptions about "the student" what they know, believe, and can do. Until quite recently preconceptions about HE applicants (certainly in the "old" universities) were based on a traditionally envisaged UK student body - think middle-class kids who have had a similar educational experience, who are practised at producing well-argued essays, and whose first language is, naturally, English. In a leading university the assumption has been that high-calibre, well-qualified students will not have difficulty in adjusting to the demands of their chosen degree. For the international student it can't be assumed that this adjustment will "just happen". You need to think who, when, where and how it's going to happen - a professional English for Academic Purposes (EAP) unit? Academic staff? Before registration? As part of on-going "in-sessional" support? Second, admissions policy is based on the assumption that you only admit a student if you think that they have a realistic chance of passing the course. Admissions tutors are mainly concerned with transcripts, grades, references - the academic "profile" of the applicant in terms of the course requirements.The system is not geared up to deal adapted with permission: Sandra Haywood, University of Nottingham with the applicant who is an able scholar, but who doesn't have the communicative ability to succeed on the course. Generally language level and academic calibre are seen as inextricably linked, and in a mono-lingual context that isn't a bad assumption. But it tends to make academics overly optimistic about the ability to cope of a "high-calibre", but linguistically weak, applicant.(I would argue that if you are serious about increasing international numbers, English ability becomes one of the defining characteristics of a high-calibre applicant, rather than something incidental.) And it's not only communication: students from different academic cultures can have very different perceptions of core academic concepts such as plagiarism, criticism of authorities, and argument structure. In short, almost the entire academic toolbox. It's particularly on something like a taught masters course, that, if the student isn't at the right level on day one, they'll be at a significant disadvantage throughout the course. And much more debate is also needed about what the "right" level for different degree courses is. The regulatory minimum English level in many British institutions is band 6.0 on the Ielts test, with no less than 5.0 in any element (Ielts scores range from zero to nine). Those involved in English language teaching will know how very weak, say, a 5.0 in writing can be. Some degree courses assess oral tasks (many MBAs for instance), but some of the alternatives to Ielts don't test speaking.Both these issues raise the question of how an equitable decision is made to admit a student. This brings us back to the assumption that if an applicant is accepted they have a good chance of passing the course. For this to happen effectively for the international student you need to move the English question from the margin to the centre of your planning. If you don't, the risks are that an international student will have both language weaknesses and a very different set of assumptions about academic conventions. The effects of having one or two students in this position may be manageable uncomfortable for the student, and expensive in terms of additional teaching/support, but not damaging to the institution. When you reach a critical mass in the student body, the real costs of not thinking seriously about the impact of high numbers of international students is far reaching. You either lower standards to get students through; or you live with unacceptably high failure rates; or you throw resources (extra teaching) at the problem to get the students through at the right level. Not having students with full "academic toolboxes" and the ability to cope with the language demands of their courses is a hidden risk to the whole university. If the challenge is not met, then this means more than the failure of the individual course in time it undermines the university as a whole, by diminishing standards or destroying its brand. adapted with permission: Sandra Haywood, University of Nottingham The HE sector is dealing with this in a variety of ways. Many of the "new" institutions have a tradition of taking students with a range of learning styles and with greater need of support. The majority of the "old" universities have been (slowly at times) catching up with the issues of quality assurance and admission policy since the first big foreign student expansion in the 1970s. It would be extremely useful to have a forum for interested academics and administrators to exchange, dare I say it, best practice. The Association of Lecturers in English for Academic Purposes (Baleap), provides this for EAP professionals, but wider institutional engagement can be lacking. So the successful expansion of a university from serving a culturally and economically homogeneous elite, to admitting a wider student body involves not only salivating over the benefits, but also meeting the costs. At the University of Nottingham we've come to think of this more mature strategy in terms of "internationalisation" in contradistinction to straight "international recruitment". It's a process with deep repercussions for the whole institution if undertaken. What you can't hope to do is ignore the demands of the international student, take their fees, and expect to carry on just as before. If the cost is met, then the university gains the essential international dimension. Hence the cost of English provision is an investment, not an expense. For the 21stcentury institution, EAP needs to be very prominent in the business plan. An alternative, reactive, model is inefficient and potentially unethical. It's rooted in an era when the presumption was that student, tutor, course administrators and external examiners all "spoke the same language", both literally and metaphorically. That given is being challenged on a daily basis, and will continue to be. Dr Rebecca Hughes is director of the University of Nottingham's Centre for English Language Education EducationGuardian.co.uk Guardian Newspapers Limited 2004 adapted with permission: Sandra Haywood, University of Nottingham