Lecture 6

advertisement

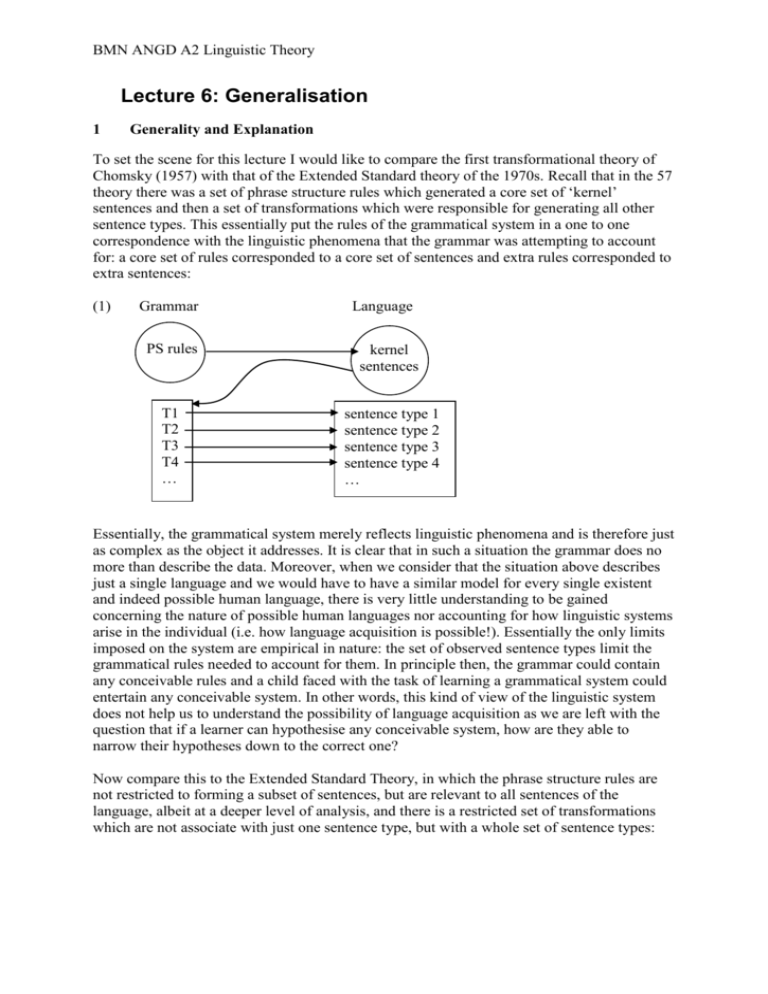

BMN ANGD A2 Linguistic Theory Lecture 6: Generalisation 1 Generality and Explanation To set the scene for this lecture I would like to compare the first transformational theory of Chomsky (1957) with that of the Extended Standard theory of the 1970s. Recall that in the 57 theory there was a set of phrase structure rules which generated a core set of ‘kernel’ sentences and then a set of transformations which were responsible for generating all other sentence types. This essentially put the rules of the grammatical system in a one to one correspondence with the linguistic phenomena that the grammar was attempting to account for: a core set of rules corresponded to a core set of sentences and extra rules corresponded to extra sentences: (1) Grammar Language PS rules kernel sentences T1 T2 T3 T4 … sentence type 1 sentence type 2 sentence type 3 sentence type 4 … Essentially, the grammatical system merely reflects linguistic phenomena and is therefore just as complex as the object it addresses. It is clear that in such a situation the grammar does no more than describe the data. Moreover, when we consider that the situation above describes just a single language and we would have to have a similar model for every single existent and indeed possible human language, there is very little understanding to be gained concerning the nature of possible human languages nor accounting for how linguistic systems arise in the individual (i.e. how language acquisition is possible!). Essentially the only limits imposed on the system are empirical in nature: the set of observed sentence types limit the grammatical rules needed to account for them. In principle then, the grammar could contain any conceivable rules and a child faced with the task of learning a grammatical system could entertain any conceivable system. In other words, this kind of view of the linguistic system does not help us to understand the possibility of language acquisition as we are left with the question that if a learner can hypothesise any conceivable system, how are they able to narrow their hypotheses down to the correct one? Now compare this to the Extended Standard Theory, in which the phrase structure rules are not restricted to forming a subset of sentences, but are relevant to all sentences of the language, albeit at a deeper level of analysis, and there is a restricted set of transformations which are not associate with just one sentence type, but with a whole set of sentence types: Mark Newson (2) Grammar Language PS Rules constraints T1 T2 T3 Note that the structure of the grammar does not simply reflect that of the language and moreover, while the language may involve fairly complex phenomena, the grammar remains relatively simple. In this way the grammar is more than just a translation of the linguistic phenomena into descriptive rules, but goes some way to improving our understanding of the phenomena itself. The other advantage of this kind of grammatical system is that as the rules themselves are not specifically related to language particular structures, but to something far more general, the rules themselves may have greater application to other languages and as such they represent something far more indicative of the basic nature of human languages as a whole. Obviously languages differ from one another, but from this perspective, given that each rule is associated with a wide range of phenomena, it might be that small alterations in the grammar result in wide ranging differences in observable languages. If what has to be learned is limited to such small differences in the grammatical system, the whole question of how language can be acquired is more easily answered. The grammatical system itself imposes huge restrictions on the notion of a possible human grammar and as such the task of language learning is much simplified. What the above discussion illustrates is the relationship between the generalisation of linguistic rules and the explanatory content of the theory within which those rules are stated. In a nutshell, the more general the grammatical system, the more explanatory the theory. In this lecture, we will discuss how the developments that took place in the 1970s along the lines sketched above culminated at the beginning of the 1980s in a theory which attained an unprecedented level or explanation. We will concentrate on two grammatical areas, the phrase structure rules and the transformation component. 2 Phrase Structure and X-bar theory Phrase Structure rules were Chomsky’s formalisation of the Structuralist idea of Immediate Constituent Analysis. From the start they were fairly descriptive devices capable of modelling any possibility for constituent structure. So if an NP contained a determiner 2 Generalisation followed by a noun, this was just as easy to model as if an NP were to contain a verb followed by a preposition: (3) a b NP → Det N NP → V P The fact that only one of these possibilities is actual in any language is then, as far as the basic theory of phrase structure based on such notions is concerned, pure accident. In other words, given that this observation is clearly no accident, the theory cannot explain the facts. The structuralists had noted that some phrases are replaceable by one of its constituents, or in other words that a part of the phrase can function as the whole. So, to take a famous example from Bloomfield (1933): (4) a b poor John ran away John ran away Here the phrase poor John is replaced by John and hence the single noun can function as the whole phrase indicating the noun’s centrality within the phrase. The term head was given to such central elements, and phrases which had heads were called endocentric. Not all linguistic constituents were endocentric, however. The most obvious unit that cannot be replaced by one of its constituent being a sentence: (5) a b c poor John ran away poor John ran away While (5a) has the status of a sentence, neither (5b) nor (5c) do. Nor does any other constituent of (5) for that matter. Hence it was proposed that sentences are exocentric, lacking a head. It is clear however that a phrase structure rule of the form X → Y Z cannot capture the notion head and hence endocentric and exocentric structures are given the same treatment: (6) NP → Adj N S → NP VP While we can say that the noun is the head of the noun phrase in the first rule, there is nothing in this rule that informs us of this apart from the apparently descriptive accident that the phrase is labelled with the same category symbol as the noun. Given that in principle (3b) is a possible phrase structure rule and there is no head of this NP we can see that phrase structure rules are not capable of capturing the notion of endocentricity nor the connected notion of a head. After more than ten year of working with phrase structure rules, Chomsky (1970) proposed a revision to the phrase structure component of the grammar, which has since become known as X-bar theory. Chomsky’s proposal was not particularly detailed and was virtually tacked on to the end of a paper about the difference between derived nominals and gerunds, which need not concern us here. The main point of the proposal was to capture certain similarities between certain elements and their dependants. Starting with verbs, which had traditionally 3 Mark Newson been subcategorised in terms of their following dependants (transitive verbs having objects, prepositional verbs having prepositional complements, etc.), Chomsky observed that nouns and adjectives, even those not derived from verbs, can also be subcategorised along similar lines: (7) a b c treat [with penicillin] treatment [with penicillin] treatable [with penicillin] book [about linguistics] fond [of chocolate] The phrase structure grammar would seem to contain the following rules therefore: (8) VP → V Comp NP → N Comp AP → A Comp where ‘Comp’ stands for the dependent phrase or ‘complement’. Clearly there is a generalisation to be had here which is entirely missed by stating these three separate rules. In each case the phrase is endocentric and the head precedes the complement. Chomsky’s proposal was to capture this generalisation by using a category variable X to represent the head and the category of the phrase it heads: (9) X' → X YP The symbol X' (pronounced X bar) represents a phrase whose category is determined by the head and thus this system is able to capture the notion of an endocentric constituent. Chomsky also saw the need to include material which preceded the head, such a determiners, auxiliary verbs and degree adverbs: (10) a b c the book have gone so tall He termed these elements specifiers and proposed the following rule: (11) X" → Spec X' The category X" (pronounced X double bar) represents the full phrase and hence phrases generated by these rules have the following structure: (12) X" Spec X' X YP Although Chomsky did not mention prepositions in the (1970) paper, it is clear that these can also be included in the set of things that X in the rules (9) and (11) can range over. Soon after, then, X was taken to range over N, V, A and P. 4 Generalisation In the 1970 paper, it was never really stated what the status of the rules in (9) and (11) were supposed to be taken as, but it seems that in the period that followed they were generally assumed to be a kind of template for possible phrase structure rules. For example, this was how they were taken in Jackendoff (1977), which was one of the major work at the time on the subject of X-bar syntax. The reason for this was the fact that there still seemed to be phenomena which were idiosyncratic to certain phrases and as X-bar rules do not distinguish between phrases of different types, specific rules for NPs, VPs, etc. were still needed. For example, it is well known that while verbs and prepositions can take NP complements, nouns and adjectives cannot: (13) a b c d tell him to him * picture him * capable it picture of him capable of it This cannot be a lexically determined thing as is not something specific to particular lexical items, but is something that is true of a whole category. The only place that such generalisations can be captured therefore is in the grammar and the phrase structure component seems to be the best place for them. Hence there was a need for rules such as the following: (14) V' → V NP P' → P NP N' → N PP A' → A PP Given that these rules conform to the pattern set down by the X-bar rule in (9) they were considered valid under the view that the role played by (9) was to licence possible phrase structure rules which were of a more specific nature. In a sense, the relationship between the X-bar rules and phrase structure rules is similar to the relationship between transformations and constraints on transformations. Although this position is more restricted an general than that which held prior to 1970, it still isn’t entirely satisfactory as there are still construction specific rules which are therefore of a descriptive nature. There are no explanations in the rules in (14), for example, for why nouns and adjectives in English cannot have NP complements. However there were a number of developments which enabled steps to be made towards a greater generalisation of the system and ultimately allowing rules such as (14) to be eliminated from the grammar. Recall the Case Filter from last week. This is a filter that controls the surface distribution of NPs, forcing them to occupy Case positions. The data in (13) indicate that the complement position of nouns and adjectives is not a Case position and under this assumption, that nouns and adjectives cannot take NPs in their surface complement positions is accounted for independently and does not have to be stipulated in terms of specific phrase structure rules. Stowell (1981) proposed that all phenomena that necessitate category specific phrase structure rules can be accounted for by independent principles of the grammar and hence the phrase structure part of the grammar can be eliminated entirely, leaving only the general X-bar rules to deal with the basic structural properties of a language. The theory which emerges looks like the following: 5 Mark Newson (15) X-bar Theory Lexicon D-structure Transformations Constraints S-structure Case Theory However, at this stage of the theory there still remain at least two structures that are exocentric and hence which stand outside of X-bar theory altogether, S and S, and a large number of elements, such as determiners, auxiliaries and complementisers which are not associated with phrases and so which are also not part of the X-bar system. It is interesting to note that at this point X-bar theory was seen as a theory of the structure of certain linguistic elements, nouns, verbs, adjectives and prepositions, which were referred to traditionally as the major categories, but are also called the lexical or thematic categories, whereas the non-X-bar elements were what are traditionally termed minor categories, though these days are more often called functional categories. Clearly the traditional names ‘major’ and ‘minor’ reflects the attitude that the thematic elements are somehow more important and this attitude seemed to prevail in X-bar theory too. It is quite obvious however that this view is guided by the fact that the thematic elements carry the larger part of the semantics whereas the functional elements have only a secondary role to play in terms of meaning. While this was the kind of thing that tended to influence traditional grammars, which tended to be meaning centred, it should not have been a factor in modern grammar which has, since the structuralists, maintained that syntax and semantics are separate (if related). It wasn’t until the early part of the 1980s theoretical interest eventually turned to the functional categories and more importance began to be placed on these elements. For example Borer (1984) proposed that most important linguistic differences can be traced to differences in properties of functional categories and hence it is these that define a particular language and these properties that children have to learn when acquiring language. The first changes reflecting this newly acquired interest in functional elements came with the analysis of the clause. Recall, this was analysed as an exocentric structure as in the following: (16) S COMP S NP INFL VP COMP represents the position of the complementiser (not to be confused with Comp, the complement position in an X-bar structure) and INFL (for ‘inflection’) represents the position of the tense element (including modal auxiliaries and the infinitive marker to). Also recall 6 Generalisation that S (pronounced ‘S bar’) was an independent notion from X-bar, indicating that this element is clausal in nature, but different from S. The possibility that the clause was not exocentric was considered in the 1970s and there seemed to be two possibilities for the choice of the head. Jackendoff (1977) championed the idea that the verb was the head of the clause, making S categorially a VP. The other view was that the inflection was the head of the clause, though it was not until the 1980s that this was taken seriously and the following representation appeared (in Stowell (1981), for example): (17) S IP NP I VP NP I' I VP This suggestion actually kills two birds with one stone as not only does it provide an X-bar analysis for the S node, but it also considers the inflection to be a category capable of being a head. It also makes the head of the clause a functional element which fits nicely with the growing interest in the syntactic role of functional categories. From this move it seemed to follow naturally that S should also fall into an X-bar type analysis and the obvious move was to consider the complementiser as its head, again bringing another functional element into the realms of X-bar theory: (18) S C CP S (wh) C' C IP Recall that the wh-element, fronted in interrogatives, was not assumed to occupy the COMP position, but be adjoined to it. The CP analysis confirms the independence of the complementiser and the wh-position, but here the wh-element is moved to the specifier position. The final functional element to fall to an X-bar analysis was the determiner. Fukui (1986) and Abney (1987) both provided an analysis of what had traditionally been taken to be a phrase headed by the noun and argued that the real head was the determiner: (19) NP Det the N DP N' D' PP picture of Mary D NP the N' N PP picture of Mary 7 Mark Newson Although this is not the place to try to justify these analyses, it is worth pointing out that even from structuralist criteria taking the determiner as the head of the ‘NP’ has its justification. Recall Bloomfield’s notion of a head being a part of a phrase that can function as the whole. In Bloomfield’s example poor John, John was identified as the head, but suppose we consider another example: that dog. Clearly dog cannot function as the whole phrase here, but that can: (20) a b c he patted that dog * he patted dog he patted that From a structuralist point of view, this provided contradictory evidence for the head of this kind of phrase and hence already more sophisticated argumentation is necessary to conclude whether the head should be taken to be the noun or the determiner. Abney provides such sophisticated argumentation and concludes in favour of the determiner. To conclude this section, we have seen how a process of generalisation has been directing the development of the part of the grammar which attends to basic structural issues. Starting with phrase structure rules, which were construction specific and rather descriptive in nature, a series of developments have led to the position in which there are just two phrase structure rules: (21) XP → Spec X' X' → X YP These are clearly not construction specific and to the extent that they account for all aspects of phrase structure can be seen to attain high levels of explanatory adequacy. For example, these rules can be assumed to underlie the phrase structures of all human languages and hence pose no particular problem for learning: they can be assumed to be universal and hence part of the innate linguistic system. Languages may differ, for example in terms of whether the head precedes or follows its complement, but the general rule that the head and the complement form a constituent (X') is universal. Thus the amount of learning involved in this aspect of language is minimal and can be done on the basis of exposure to quite simple data. 3 Transformations We have seen how transformations started off as structure specific rules in the 1960s and as a result of the addition of constraints became far more general. Indeed, by the end of the 1970s it was generally accepted that there were two main transformations, one for moving NPs into subject positions and one for moving wh-elements into COMP. Besides these there were a number of other transformations which seemed to be of a stylistic nature and were generally optional, so perhaps belonging to an entirely different part of the grammar. The two major movements, NP-movement and Wh-movement, could not be further reduced as it appeared they were subject to different conditions: NP-movement being restricted by the Tensed S Condition and the Specified Subject Condition and Wh-movement being restricted by the Crossover Conditions (see lecture 4). Perhaps this was not an impossible situation, but it still raised questions that could only be solved in a stipulatory manner, such as why there are these two transformations and why they have the particular properties that they do. 8 Generalisation Once again, developments in other parts of the grammar proved helpful to overcome these problems. Specifically it was the development of trace theory that allowed the final step in the generalisation of the transformational component. We will go into the details more fully next week, but the observation was that the traces involved in structures formed by various movement phenomena had different properties. Consider a straightforward case of NPmovement, for example: (22) a b c John1 seemed [ t1 to be rich] * John1 seemed [ t1 is rich] * John1 seemed [ Mary to like t1] We see that an NP is allowed to move out of the subject position of a non-finite clause, but not out of a finite clause (violating the Tensed S Condition) or out of an object position (violating the Specified Subject Condition). This pattern is repeated in phenomena concerning the referential properties of certain pronouns: (23) a b c John1 believes [himself1 to be smart] * John1 believes [himself1 is smart] * John1 believes [Mary to like himself1] In (23), we use indexes to indicate the referent of the pronoun. What we see is that a reflexive pronoun in the subject position of a non-finite clause can refer to an element in the dominating clause, but not if it is in a finite clause or in object position. These data can be handled if we assume that the traces in (22) are subject to the same grammatical principles as the pronouns in (23), or in other words, these traces and pronouns form a coherent class of elements, known as anaphors. With this assumption, then, these restrictions can be factored out from the movement process altogether and whatever the more general conditions that determine the properties of anaphors, accounting for the Tensed S Condition and Specified Subject Condition, are not to be taken as constraints on particular movements all. A similar move can account for Crossover phenomena too. Recall that a wh-element is not allowed to move over the top of a coreferential element: (24) a b who1 t1 said [he1 likes Mary] * who1 did he1 say [t1 likes Mary] In this case we cannot liken the behaviour of the trace to that of a reflexive pronoun, as replacing the trace with such a pronoun gives an ungrammatical sentence in both cases: (25) a b * himself1 said [he1 likes Mary] * he1 said [himself1 likes Mary] However, if we replace the trace with a full referential NP we get the required result, so in this case it seems that the trace behaves like a referential expression: (26) a b John1 said [he1 likes Mary] * he1 said [John1 likes Mary] 9 Mark Newson Again, factoring these conditions out of the movement process altogether and imposing them as restrictions on types of traces, we no longer need to claim that there is a type of movement which is restricted by a specific constraint. The part of the grammar which was developed to account for the referential properties of elements such as reflective and personal pronouns and referential expressions such as names was called Binding Theory and its conditions act like Filters applying at S-structure, defining possible referential interpretations for the relevant elements. Seeing traces as having referential properties and hence being subject to the principles of Binding Theory was one of the major developments which allowed apparently structure specific restrictions to be factored out of transformations entirely. Because of these developments, the transformational component was ultimately reduced to a single transformation. This transformation did not have to stipulate what element had to move, as this was determined by independent considerations such as the Case filter – forcing NPs to move out of Caseless positions, for example. Nor did it have to stipulate where the element had to move to – the Case Filter required Caseless NPs to move to Case positions. In fact all that was required of the transformation component was the statement that things can move and all the specific details of particular movements, which had previously been encoded in the transformations themselves, was factored out to other independently motivated parts of the grammar. The transformation required was then: (27) Move Move anything anywhere Obviously this is the most general transformation there could possibly be, something that might easily be part of an innate system and given that in most languages there is some indication that some elements undergo movement processes it is a universal aspect of languages too. Of course, there are differences in what moves where in languages: not all languages move wh-elements to the front of the clause in interrogatives, for example. But as these facts are not specific to the transformational component, but to other aspects of the grammar, they do not need to be encoded in the transformation rule itself. The grammar we end up with is as follows: 10 Generalisation (28) X-bar Theory Lexicon D-structure Move S-structure Constraints Case Theory Binding Theory 4 Conclusion In the grammatical system represented in (28) we can start to see the beginnings of the theory that developed in the 1980s, known as Government and Binding theory. One of the most obvious features of this system is its modular nature: there are independent grammatical modules, each of which addresses specific grammatical phenomena, such as X-bar theory addressing basic structural issues and Binding Theory addressing referential phenomena, and each of which contains a small number of general grammatical principles. The complexity of the linguistic system does not stem from the complexity of the grammatical rules themselves, but from the complex way these rules interact with each other. For example, Case theory imposes a simple restriction on S-structure, that all NPs/DPs must be in Case positions, and this in turn places requirements on movement, forcing elements to move out of Caseless positions into positions where they can get Case. The movement component itself, however, simply permits movements of any kind, but only those which serve to satisfy the Case Filter will give rise to grammatical structures. Given that the structure of the grammar can be taken to be universal, and the simple principles of the grammatical modules are also general enough to be considered universal, this model goes a long way to solving the question of how language acquisition is possible. What has to be learned are the lexical elements and their properties, which given that this amounts to a finite body of knowledge, poses no particular logical problem, and also some fairly superficial differences in how the principles themselves are to be applied, such as whether heads precede complements. Because of the complex interaction between the simple and general modules of the grammar, however, simple changes in one module might result in dramatic differences in terms of what structures are grammatical between languages. So while languages may look to differ one from another in vast and complex ways, the actual difference between the grammatical systems, which is after all what has to be acquired, may be relatively minor. Such was the optimistic hope of 1980s grammar, at least. We shall see that while some of this optimism was justified, ultimately Government and Binding theory raised as many questions as it solved, however. 11 Mark Newson References Abney, Stephen Paul 1987 ‘The English Noun Phrase in its Sentential Aspect’, PhD. dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, Mass. Bloomfield, Leonard 1933 Language, Rinehart and Winston, New York. Borer, Hagit 1984 Parametric Syntax, Foris, Dordrecht. Chomsky, Noam 1970 ‘Remarks on Nominalisation’, in Jacobs, R. and P.S. Rosenbaum (eds.) Readings in English Transformational Grammar, Ginn and Co., Waltham, Mass. Fukui, N 1986 ‘A Theory of Category Projection and its Applications’, Ph.D. dissertation, MIT. Jackendoff, Raymond 1977 X-bar Syntax, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. 12