Babylonian Mathematics: Classroom Activities 1

advertisement

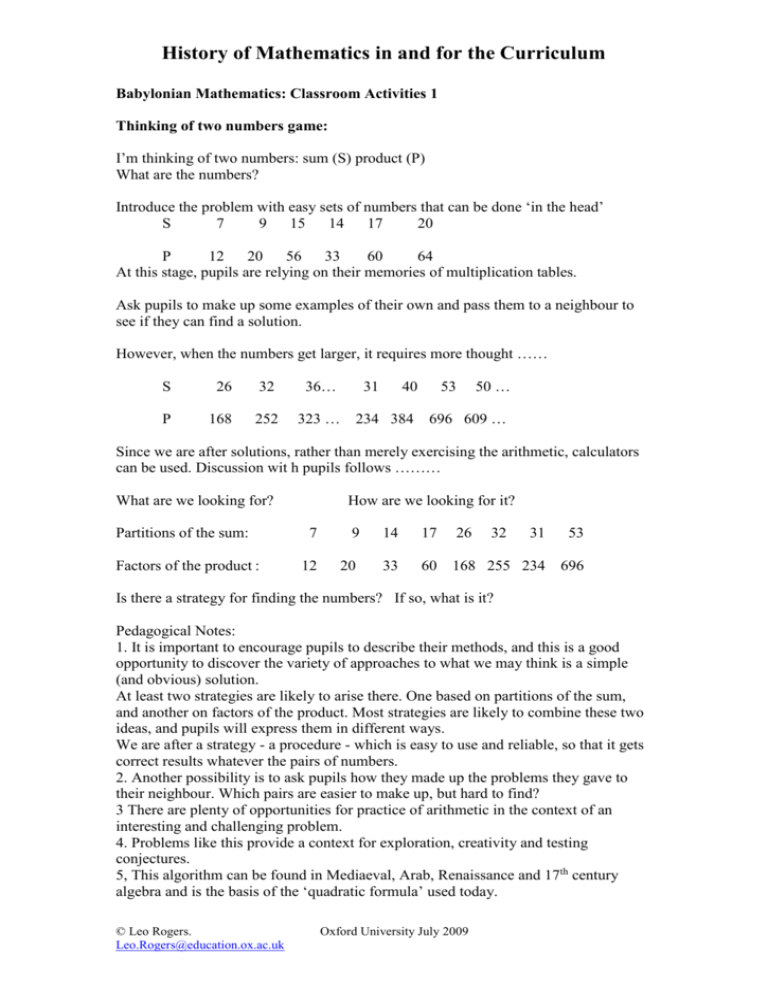

History of Mathematics in and for the Curriculum Babylonian Mathematics: Classroom Activities 1 Thinking of two numbers game: I’m thinking of two numbers: sum (S) product (P) What are the numbers? Introduce the problem with easy sets of numbers that can be done ‘in the head’ S 7 9 15 14 17 20 P 12 20 56 33 60 64 At this stage, pupils are relying on their memories of multiplication tables. Ask pupils to make up some examples of their own and pass them to a neighbour to see if they can find a solution. However, when the numbers get larger, it requires more thought …… S 26 32 36… P 168 252 323 … 40 31 234 384 53 50 … 696 609 … Since we are after solutions, rather than merely exercising the arithmetic, calculators can be used. Discussion wit h pupils follows ……… What are we looking for? Partitions of the sum: Factors of the product : How are we looking for it? 7 9 14 17 26 32 31 53 12 20 33 60 168 255 234 696 Is there a strategy for finding the numbers? If so, what is it? Pedagogical Notes: 1. It is important to encourage pupils to describe their methods, and this is a good opportunity to discover the variety of approaches to what we may think is a simple (and obvious) solution. At least two strategies are likely to arise there. One based on partitions of the sum, and another on factors of the product. Most strategies are likely to combine these two ideas, and pupils will express them in different ways. We are after a strategy - a procedure - which is easy to use and reliable, so that it gets correct results whatever the pairs of numbers. 2. Another possibility is to ask pupils how they made up the problems they gave to their neighbour. Which pairs are easier to make up, but hard to find? 3 There are plenty of opportunities for practice of arithmetic in the context of an interesting and challenging problem. 4. Problems like this provide a context for exploration, creativity and testing conjectures. 5, This algorithm can be found in Mediaeval, Arab, Renaissance and 17th century algebra and is the basis of the ‘quadratic formula’ used today. © Leo Rogers. Leo.Rogers@education.ox.ac.uk Oxford University July 2009 History of Mathematics in and for the Curriculum A Strategy? S = 14, P = 33; S = 17, P = 60; S = 31, P = 234 15 ½ 8½ 7 6 5 4 3 8 7 6 5 8 9 10 11 3 + 11 = 14 3 x 11 = 33 15 14 13 12 9 10 11 12 5 + 12 = 17 5 x 12 = 60 16 17 18 19 13 + 18 = 31 13 x 18 = 234 Take half the Sum number, then add and subtract to find pairs for testing the product. Checking S = 14, P = 33 S = 32, P = 252 S 7 2 S 16 2 3, 11 14,18 7 4 7 4 16 2 16 2 49 16 256 4 33 252 Products can also be expressed using the ‘grid’ display. 7 2 1 2 49 4 7 4 7 4 1 4 x 7 2 1 2 Many interesting properties of the above may be noted: the stepwise procedure will obtain the product numbers; the conjugate brackets (a - b)( a + b) produce a clear example of the difference of two squares; the grid display exposes the partial products of the binary multiplication; the opposite signs clearly show that there are two factors which cancel each other; etc. Other variations found in the Babylonian tablets are: Difference of two numbers, (a - b) and their Product ab Sum of two numbers, (a + b) and the sum of their Squares (a2 + b2) Difference of two numbers, (a - b) and the sum of their Squares (a2 + b2) In each case, what would be the procedures for finding solutions? © Leo Rogers. Leo.Rogers@education.ox.ac.uk Oxford University July 2009

![afl_mat[1]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005387843_1-8371eaaba182de7da429cb4369cd28fc-300x300.png)