Fluid properties

advertisement

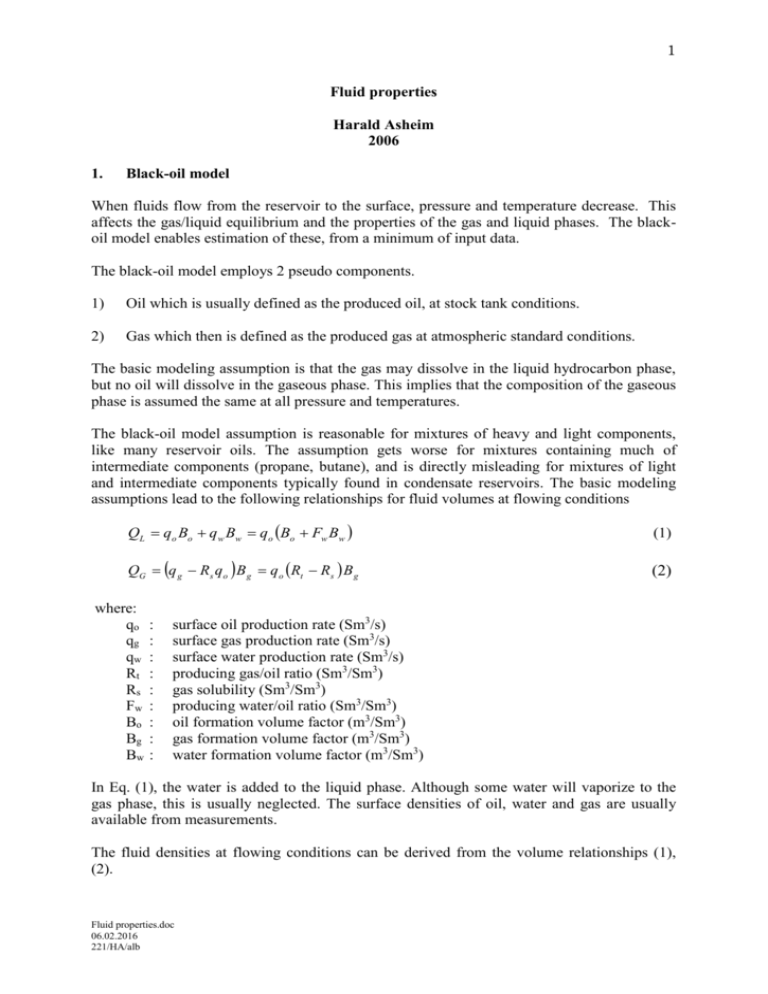

1 Fluid properties Harald Asheim 2006 1. Black-oil model When fluids flow from the reservoir to the surface, pressure and temperature decrease. This affects the gas/liquid equilibrium and the properties of the gas and liquid phases. The blackoil model enables estimation of these, from a minimum of input data. The black-oil model employs 2 pseudo components. 1) Oil which is usually defined as the produced oil, at stock tank conditions. 2) Gas which then is defined as the produced gas at atmospheric standard conditions. The basic modeling assumption is that the gas may dissolve in the liquid hydrocarbon phase, but no oil will dissolve in the gaseous phase. This implies that the composition of the gaseous phase is assumed the same at all pressure and temperatures. The black-oil model assumption is reasonable for mixtures of heavy and light components, like many reservoir oils. The assumption gets worse for mixtures containing much of intermediate components (propane, butane), and is directly misleading for mixtures of light and intermediate components typically found in condensate reservoirs. The basic modeling assumptions lead to the following relationships for fluid volumes at flowing conditions QL qo Bo q w Bw qo Bo Fw Bw (1) QG q g Rs q o B g q o Rt Rs B g (2) where: qo qg qw Rt Rs Fw Bo Bg Bw : : : : : : : : : surface oil production rate (Sm3/s) surface gas production rate (Sm3/s) surface water production rate (Sm3/s) producing gas/oil ratio (Sm3/Sm3) gas solubility (Sm3/Sm3) producing water/oil ratio (Sm3/Sm3) oil formation volume factor (m3/Sm3) gas formation volume factor (m3/Sm3) water formation volume factor (m3/Sm3) In Eq. (1), the water is added to the liquid phase. Although some water will vaporize to the gas phase, this is usually neglected. The surface densities of oil, water and gas are usually available from measurements. The fluid densities at flowing conditions can be derived from the volume relationships (1), (2). Fluid properties.doc 06.02.2016 221/HA/alb 2 G L g q g Rs q o QG o g (3) Bg g Rs q o w q w QL o g Rs w Fw Bo Bw Fw (4) where: o : surface oil density (kg/Sm3) g : surface gas density (kg/Sm3) w : surface water density (kg/Sm3) 2. Gas solubility As long as liquid and gas are in contact and in thermodynamic equilibrium, the liquid will be gas saturated at the actual pressure and temperature. The saturation pressure for a gas-oil system is the pressure at which the gas solubility equals the producing gas/oil ratio, Rt Rs pb , T Rt (5) where: pb : saturation pressure T : fluid temperature Figure 1. Gas solubility, variation with pressure at constant temperature. Fluid properties.doc 06.02.2016 221/HA/alb 3 Thus correlations for the gas solubility can be used to estimate the saturation pressure for a given Rt, and vice versa. From basic thermodynamics the following solubility behaviour may be expected. a) b) c) Solubility proportional to pressure (Henry's law) Solubility inversely proportional to the exponential of 1/T (after Clausius - Clapeyron's law) Heavy gas more soluble than light gas. Heavy oil dissolves less gas than light oil (molecular similarity). Actually most gas solubility correlations have originally been presented as methods for saturation pressure estimation. Figure 1 shows a typical variation of the gas solubility with pressure. These idealized solubility mechanisms can be recognized in the correlation by Standing /1947/. Standings correlation Rs 0.571 g 100.0151API10 0.00198T cR p 1.41.205 (6) 0.00590 g 10 2.14 / o10 0.00198T cR p 1.41.205 where: Rs g p T gas solubility (Sm3/Sm3) separator gas gravity fluid pressure (bar) fluid temperature (K) 141.5 131.5 API : API gravity API o o cR : : : : = stock tank oil specific gravity (ratio: oil-density/water-density) = calibration constant cR = 0.797 estimated by Standing for California crudes Standing found that the calibration constant, cR, depends on crude type. If PVT data are available, this constant may be changed to match measurements. Glasø's correlation, for the input parameter units as above. Rs g 5.615 API 1.21201.8T 4600.2108 103.5181 1.2404 0.397 1og10 p 0.5 (7) Glasø /1980/ developed a correlation based on North Sea data from 6 different reservoirs. It appears to be less consistent with general thermodynamic principles than Standings Fluid properties.doc 06.02.2016 221/HA/alb 4 correlation. Other solubility correlation has been given by Lasater /1958/ and by Vazquez and Beggs /1977/. 3. Oil formation volume factor When gas dissolves in the oil, the mass contained in oil phase increases. This makes the pressure-volume behavior of liquid below the saturation pressure fundamentally different than from above the saturation pressure. Figure 2 show a typical variation of the formation volume factor with pressure. Figure 2. Oil formation volume factor, at constant temperature. Below the saturation pressure: Both liquid and gasous phases will be present, and the following effects may be expected a) Expansion of the liquid volume by the dissolved gas. This should be roughly proportional to amount of gas dissolved and increase by increasing molecular size (mol volume) of the gas. b) Expansion of liquid volume by increased temperature. However, increased temperature will also reduce gas solubility. c) Compression by increased pressure. The overall effect of pressure increase at constant temperature will be increased liquid volume. Temperature increase at constant pressure will result in reduced liquid volume, Fluid properties.doc 06.02.2016 221/HA/alb 5 caused by vaporization. These fundamental mechanisms are quantified in the empirical correlation by Standing /1947/. Standing's correlation, for input parameter units are as for Eq. (6) above. g Bo cB 0.952 103 o 1.2 0.5 Rs 0.401 T 103 (8) where: cB : calibration constant. cB = 0.9759 estimated by Standing for California crudes If PVT data are available, the calibration constant may be adjusted such that the estimates match the measurements. Glasø's correlation 2 Bo 1 10 6.58 2.91log10 B*0.276log10 B* g B* 5.615 o (9) 0.526 Rs 1.74 T 445 (10) Glasø /1980/ has developed a correlation based on data from 6 different North Sea reservoirs. Again this appears to be less consistent with thermodynamic principles than Standings correlation. Other correlations have been developed by Vazquez and Beggs /1977/. Above the saturation pressure Above the saturation pressure all gas will be in solution, and only a liquid oil phase present. This liquid will compress with increasing pressure. The compressibility factor is generally defined as c 1 dV 1 dBo V dp Bo dp (11) For ideal liquids, the compressibility factor is constant. Assuming constant compressibility, the volume behavior above saturation pressure may be expressed by integrating (11). This gives Bo Bob ec p pb Fluid properties.doc 06.02.2016 221/HA/alb (12) 6 where: c : constant compressibility factor (1/bar) pb : saturation pressure (bubble point pressure) Bob : formation volume factor at saturation pressure A compressibility factor correlation has been developed by Vazquez and Beggs /1980/. c 104 2.81 Rt 3.10 T 171 o 118 g 1102 (13) p The order of magnitude of this compressibility factor is typically: c 10 5 10 2 bar 1 Vazquez and Beggs /1980/ offered the compressibility factor correlation (13) to be used in the volume behavior equation (12). This is inconsistent, since the ideal volume behavior equation assumes constant compressibility, while Vazquez-Beggs correlation predicts compressibility that varies with pressure. That inconsistency may be resolved by 2 alternative approaches a) The compressibility factor may be estimated by Vazquez-Beggs correlation (13), at an averaged pressure and temperature. This provides an averaged compressibility factor that may be used as approximation in the ideal fluid relation (12). b) The compressibility relation (11) may be solved with compressibility factor expressed by the Vazquez-Beggs correlation (13). For fixed temperature, such solution gives 104 2.81 Rt 3.10 T 171 o 118 g 1102 p Bo Bob b p (14) Since the compressibility factor usually is very small, much difference between the two approaches should not be expected. The latter (15) was recommended by Whitson & Brule /2000/. 4. Gas formation volume factor The volumetric behaviour of gas is described by the general gas equation pV = n z RT (15) The gas formation volume factor is by definition the ratio of volume at given temperature and pressure, to volume at standard surface temperature and pressure. By the general gas equation, this is expressed as Bg where: z po T z p T o zo : gas z-factor (supercompressibility factor) Fluid properties.doc 06.02.2016 221/HA/alb (16) 7 At surface conditions natural hydrocarbon gas behaves close to ideal. Thus, z 1 at surface pressure. At downhole condition pressure, the z-factor is usually in the order of 0.7-0.9. For natural gas mixtures, the z-factor can be estimated using the Standing-Katz correlation, Fig. 3. Figure 3 Supercompressibility factor for petroleum gases, Standing & Katz /1942/ The pseudo reduced pressure and temperatures needed to estimate the z-factors are defined as actual gas pressure divided by pseudo critical pressure, and actual gas temperature divided by pseudo critical temperature. The pseudo critical pressure and temperature of gas mixtures are defined as compositional averages of critical pressures and temperatures of individual components. Fluid properties.doc 06.02.2016 221/HA/alb 8 When gas composition is not known, pseudo critical pressure and temperature may be estimated based on gas gravity, implicitly assuming some typical composition. For associated gas, such correlations have been worked out by Sutton/1985/. Associated gas usually has relatively more heavy component than found in gas fields. Sutton’s correlations are given below, algebraically and graphically Tpc 94.0 194.2 g 41.1 g2 p pc 58.18 9.032 g 0.248 g2 Figur Pseuodocritcal properties by Suttons correlations 5. Oil viscosity The oil viscosity of dead (gas-free) oil is easily measured. However, to measure the viscosity of gas-saturated oil at elevated pressure is much more complicated. Therefore, the oil viscosity is often measured at surface pressure and reservoir temperature, and adjusted for gas content. Chew and Connally /1959/ presented a graphical correlation to adjust the dead oil viscosity according to the gas solubility. The correlation, as shown in Figure 4 was developed 457 crude oil samples. Fluid properties.doc 06.02.2016 221/HA/alb 9 Figure 4 Effect of gas saturation on oil viscosity Standing /1981/ expressed the above correlation in a mathematical form as follows: os a od b (17) where: a 10 Rs 6.910 6 Rs 4.2103 4 b 0.68 10 4.8410 Rs 3 0.25 10 6.1810 Rs 2 0.062 10 2.110 Rs Beggs and Robinson /1975/ use the same correlation formula (14), but predict the parameters slightly simple a 4.406 Rs 17.8090.515 Fluid properties.doc 06.02.2016 221/HA/alb 10 b where: os od Rs 3.036 Rs 26.7140.338 : viscosity of the oil at the bubble-point pressure, cp : viscosity of the dead oil at atmospheric pressure and reservoir temperature, cp : gas solubility (Sm3/Sm3) The dead oil viscosity is preferably measured. There exist several correlations for the dead oil viscosity as function of temperature and gravity. None of these are very reliable. According to Sutton and Farashad /1984/, one of the better correlations is by Glasø /1980/. od 4.15 10 9 T 256 3.44 log 10 API a (18) where a = 10.313 log10 (T-256) - 33.81 Undersaturated oil When all gas has been dissolved, further pressure increases will compress the oil, thus, reducing the distance between molecules and increasing the viscosity. Oil viscosity above saturation pressure may be predicted by Beal’s correlations, analytically expressed as o os 10 3 0.35 os1.6 0.55 os 0.56 p p (19) s where: os : viscosity of oil at saturated pressure (cp) ps : saturation pressure (bar) p : pressure (bar) 6. Gas viscosity The gas viscosity at elevated pressure and temperature is usually estimated using the charts by Carr-Kobayashi-Burrows /1954/. Dempsey /1965/ expressed their chart g ln T pr 1 a0 a1 p pr a2 p 2pr a3 p 3pr a a T pr a4 a5 p pr a6 p 2pr a7 p 3pr 2 T pr 3 T pr Fluid properties.doc 06.02.2016 221/HA/alb 8 a9 p pr a10 p 2pr a11 p 3pr 12 a13 p pr a14 p 2pr a15 p 3pr (20) 11 where: Tpr ppr a0-a15 a0 a1 a2 a3 a4 a5 a6 a7 = = = = = = = = : pseudo-reduced temperature of the gas mixture : pseudo-reduced pressure of the gas mixture : coefficients of the equations are given below - 2.46211820 2.97054714 - 2.86264054 (10-1) 8.05420522 (10-3) 2.80860949 - 3.49803305 3.60373020 (10-1) - 1.044324 (10-2) a8 a9 a10 a11 a12 a13 a14 a15 = = = = = = = = - 7.93385684 (10-1) 1.39643306 - 1.49144925 (10-1) 4.41015512 (10-3) 8.39387178 (10-2) - 1.86408848 (10-1) 2.03367881 (10-2) - 6.09579263 (10-4) Standing /1977/ proposed a convenient correlation for calculating the viscosity of the natural gas at atmospheric pressure and reservoir temperature 1 3.0764 10 5 3.712 10 6 g T 256 8.188 10 3 6.15 10 3 log 10 g (21) The pressure of non-hydrocarbon gases affects the viscosity. This can be corrected for as follows. N2 y N2 8.48 10 3 log 10 g 9.59 10 3 CO2 yCO2 9.08 10 3 log 10 g 6.24 10 3 where: 1 T g y N 2 , y CO2 Fluid properties.doc 06.02.2016 221/HA/alb : : : : (22) (23) viscosity of the gas at atmospheric pressure and reservoir temperature, cp reservoir temperature, K gas gravity mole fraction of N2, CO2 respectively 12 References /1946/ Beal, C.: "The Viscosity of Air, Water, Natural Gas, Crude Oil and its Associated Gases at Oil Field Temperatures and Pressures", Trans. AIME, 165, 94 (1946). /1947/ Standing, M.B.: "A Pressure-Volume-Temperature Correlation for Mixtures of California Oils and Gases", API Drilling and Production pract. 1947, p. 247. /1952/ Standing, M.B.: "Volumetric Phase Behaviour of Oil Field Hydrocarbon Systems", Chevron Research Company 1952. /1954/ Carr, N.L., Kobayashi, R., and Burrows, D.B.: "Viscosity of Hydrocarbon Gases Under Pressure", Trans. AIME 201, 264 (1954) /1958/ Lasater, J.A.: "Bubble Point Pressure Correlation", Trans. AIME, 213, 1958, p.379-381. /1959/ Chew, J., and Connally, C.A.: "A Viscosity Correlation for Gas Saturated Crude Oils", Trans. AIME 216, 23 (1959). /1965/ Dempsey, J.R.: “Computer Routine Treats Gas Viscosity as a Variable”, O & G Journal, Aug. 16, 1965, p. 141. /1967/ Nemeth, L.K., Kennedy, H.T.: "A Correlation of Dewpoint Pressure with Fluid Composition and Temperature", SPEJ, June 1967, p 99. /1975/ Beggs, H.D. and Robinson, J.R.: “Estimating the Viscosity of Crude Oil Systems”, J. Petr. Techn., Sept. 1975, 1140. Fluid properties.doc 06.02.2016 221/HA/alb 13 /1980/ Glasø, Ø.: "Generalized Pressure-Volume-Temperature Correlations", JPT, May 1980, p 784-795. /1980/ Vasquez, M., Beggs, H.D.: "Correlation for Fluid Physical Property Predictions", JPT, June 1980, p. 968-970. /1981/ Standing, M.B.: Volumetric and Phase Behaviour of Oil Field Hydrocarbon Systems, Soc. Petr. Engin., Dallas, 1981. /1984/ Sutton, R.P., Farashad, F. F.: “Evaluation of Empirically Derived PVT Properties for Gulf of Mexico Crude Oils”, SPE 13172, 59th Annual Meeting, Houston, TX, 1984. /2000/ Whitson, C.H., Brule, M. R.: Phase Behavior SPE Monograph vol. 20, Henry L. Doherty series Richardson, Texas 2000 Fluid properties.doc 06.02.2016 221/HA/alb