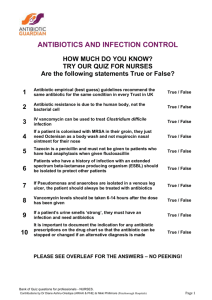

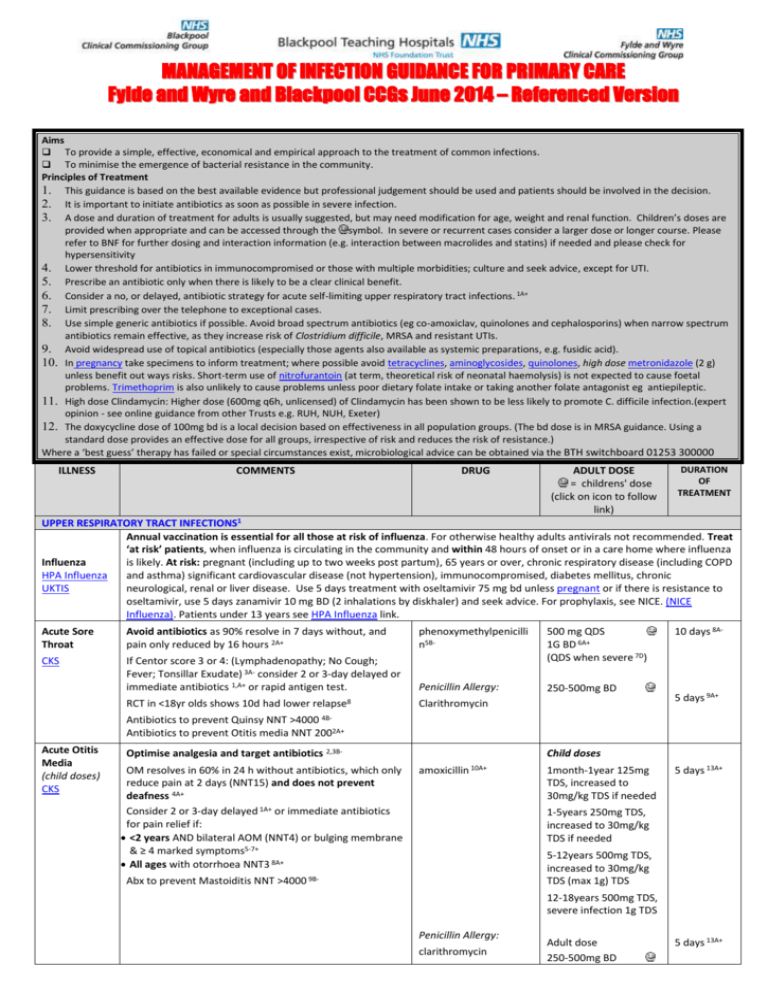

Management Of Infections Primary Care

advertisement