Prospective Study of Outcomes after Reduction Mammaplasty

advertisement

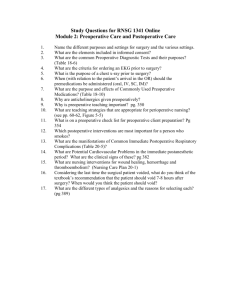

Prospective Study of Outcomes after Reduction Mammaplasty Brian J. Miller, MD, Steven F. Morris, MD, Leif L. Sigurdson, MD, Richard L. Bendor-Samuel, MD, Mike Brennan, MD, George Davis, MD, and Justin L. Paletz, MD. Macromastia is commonly associated with physical symptoms including neck, back, shoulder and breast pain, painful bra strap grooving, intertrigo, poor posture and difficulty exercising. It is also often associated with psychological symptoms related to unwanted attention, difficulty finding clothing that fits and low self-esteem. Reduction mammaplasty is widely accepted by plastic surgeons as an effective means of relieving many of these symptoms. Several studies have concluded that reduction mammaplasty benefits women with macromastia. Many of these studies were retrospective or did not make use of validated measures of health status.1-7 More recent studies have been prospective and have made use of validated outcomes tools, such as the Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF36).8-14 The patient populations described by these studies may not be comparable to our patient population due to regional variation in the ways women are selected for reduction mammaplasty. For example, pre-approval for surgery is required in some provinces based on factors such as body mass index (BMI). A prospective study of outcomes after reduction mammaplasty was designed in order to assess the effectiveness of reduction mammaplasty in our patient population, to compare preoperative and postoperative health status to the normal population, and to eventually examine the role of BMI and amount of reduction as predictors of outcome after reduction mammaplasty. Methods: Patients were enrolled prospectively by six participating surgeons. Surgeons completed a preoperative assessment form documenting height, weight and physical exam findings for each patient. Surgeons also completed an operative note form, as well as postoperative assessment forms at 1 and 6 months after surgery describing the postoperative course, length of hospitalization, time of return to work and complications. Patients completed three health questionnaires preoperatively and again 6 months postoperatively to assess health status before and after surgery. These consisted of the Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36), the Rosenberg SelfEsteem Scale, and the Symptom Inventory Questionnaire - a questionnaire describing the presence and severity of breast related symptoms. SF-36 scores before and after surgery were compared to previously published Canadian normative data.15 Demographic data was also collected. Results: Preoperatively, the most common bra cup size was DD (56%). Average BMI was 29.8 kg/m2. Breast pain on palpation was uncommon (4.3%), and shoulder grooving was almost always present (96%). The inferior pedicle technique was used most often (96%). Liposuction was occasionally performed at the time of reduction mammaplasty (13%). Drains were used in almost all cases (96%). Prophylactic antibiotics were used most of the time (74%). There were no intraoperative problems reported. The average hospital stay was 0.85 days. Average time until return to work was 26.4 days. The most common complication reported was delayed wound healing (19%). The majority of patients were employed full-time (56%), married (60%) and Caucasian (98%). Mean age was 40 yrs. Household income and education were varied. Comparison of mean preoperative and postoperative SF-36 scores showed significant improvements in seven out of eight health domains and in the physical health summary scale (p<0.01) (Fig. 1). Significant improvements were also seen in mean scores on the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (p<0.001). The Symptom Inventory Questionnaire demonstrated significant improvements in all breast related symptoms (p<0.01) and no significant change in nipple sensation or pain (p>0.05). When compared to previously published norms for the age-matched female population, mean preoperative SF-36 scores were significantly worse in the physical functioning, bodily pain and vitality domains, as well as on the physical health summary scale (p<0.0002). Mean scores for the remaining domains and the mental health summary scale were not statistically different than the normal population (p>0.05) (Fig. 2). Postoperatively, none of the SF-36 scores were significantly lower than population norms. Patients scored significantly higher than the normal population on the role physical, vitality, social function and mental health domains (p<0.05) (Fig. 3). Conclusion: Reduction mammaplasty was effective in relieving the symptoms commonly associated with macromastia. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale and SF-36 scores demonstrated a significant improvement in health status at 6 months after surgery. When compared to the normal population, SF-36 scores indicated that patients had a significant health deficit preoperatively and normalized at 6 months after surgery. The physical and mental health summary scales suggest that the preoperative burden and postoperative improvement is related more to physical health than to mental health. Further follow-up is required to determine whether this improvement persists over time. Enrollment of more patients will provide adequate numbers to allow for subgroup analysis based on BMI and amount of reduction in order to determine whether these factors are important in predicting outcome after reduction mammaplasty. 100 * * * 90 * Mean SF-36 Scores * * 80 * 70 Preop. Postop. 60 * 50 40 PF RP BP GH V SF RE MH PHS MHS SF-36 Domains and Summary Scales Fig 1. Comparison of mean preoperative and postoperative SF-36 scores. * = p<0.01. PF = physical function, RP = role physical, BP = bodily pain, GH = general health, V = vitality, SF = social function, RE = role emotional, MH = mental health, PHS = physical health summary scale, MHS = mental health summary scale. 2SD 1SD Mean Preoperative SF-36 Scores Relative to Population Norms (N) N * -1SD * * * -2SD PF RP BP GH V SF RE MH PHS MHS SF-36 Domains and Summary Scales Fig 2. Comparison of mean preoperative SF-36 scores to age and gender matched population norms. * = p<0.0002. PF = physical function, RP = role physical, BP = bodily pain, GH = general health, V = vitality, SF = social function, RE = role emotional, MH = mental health, PHS = physical health summary scale, MHS = mental health summary scale. 2SD 1SD Mean Postoperative SF-36 Scores Relative to Population Norms (N) * * * * N -1SD -2SD PF RP BP GH V SF RE MH PHS MHS SF-36 Domains and Summary Scales Fig. 3. Comparison of mean postoperative SF-36 scores to age and gender matched population norms. * = p<0.05. PF = physical function, RP = role physical, BP = bodily pain, GH = general health, V = vitality, SF = social function, RE = role emotional, MH = mental health, PHS = physical health summary scale, MHS = mental health summary scale. References 1. Brown, A.P., Hill, C., and Khan, K: Outcome of reduction mammaplasty – a patient’s perspective; Br J Plast Surg; 53; 584-587; 2000. 2. Shakespeare, V., and Postle, K: A qualitative study of patient’s views on the effects of breast-reduction surgery: a 2-year follow-up survey; Br J Plast Surg; 52; 198-204; 1999. 3. Glatt, B.S., Sarwer, D.B., O’Hara, D.E., Hamori, C., Bucky, L.P., and LaRossa, D.: A retrospective study of changes in physical symptoms and body image after reduction mammaplasty; Plast Reconstr Surg; 103; 76-82; 1999. 4. Schnur, P.L., Schnur, D.P., Petty, P.M., Hanson, T.J., and Weaver, M.S.: Reduction mammaplasty: an outcome study; Plast Reconstr Surg; 100; 875-883; 1997. 5. Boschert, M.T., Barone, C.M, and Puckett, C.L.: Outcome analysis of reduction mammaplasty; Plast Reconstr Surg; 98; 451-454; 1996. 6. Miller, A.P., Zacher, J.B., Berggren, R.B., Falcone, R.E., and Monk, J.: Breast reduction for symptomatic macromastia: can objective predictors for operative success be identified?; Plast Reconstr Surg; 95; 77-83; 1995. 7. Davis, G.M., Ringler, S.L., Short, K., Sherrick, D., and Bengtson, P.: Reduction mammaplasty: long term efficacy, morbidity, and patient satisfaction; Plast Reconstr Surg; 96; 1106-1110; 1995. 8. Memmal, C.J., Redding, J.F., Egan, L., Odom, L.C., and Casas, L.A.: Reduction mammaplasty is a functional operation, improving quality of life in symptomatic women: a prospective, single-center breast reduction outcome study; Plast Reconstr Surg; 110; 1644-1652; 2002. 9. Collins, E.D., Kerrigan, C.L., Kim, M., Lowery, J.C., Striplin, D.T., Cunningham, B., Wilkins, E.G.: The effectiveness of surgical and nonsurgical interventions in relieving the symptoms of macromastia; Plast Reconstr Surg; 109; 15561566; 2000. 10. Behmand, R.A., Tang, D., and Smith, D.J.: Outcomes in breast reduction surgery; Ann Plast Surg; 45; 575-580; 2000. 11. Blomqvist, L., Eriksson, A., and Brandberg, Y.: Reduction mammaplasty provides long-term improvement in health status and quality of life; Plast Reconstr Surg; 106; 991-997; 2000. 12. Faria, F.S., Guthrie, E., Bradbury, E., and Brain, A.N.: Psychosocial outcome and patient satisfaction following breast reduction surgery; Br J Plast Surg; 52; 448-452; 1999. 13. Shakespeare, V., and Cole, R.P.: Measuring patient-based outcomes in a plastic surgery service: breast reduction surgical patients; Br J Plast Surg; 50; 242-248; 1997. 14. Klassen, A., Fitzpatrick, R., Jenkinson, C., and Goodacre, T.: Should breast reduction surgery be rationed? A comparison of the health status of patients before and after treatment: postal questionnaire survey; BMJ; 313; 454-457; 1996. 15. Hopman, W.M., Towheed, T., Anastassiades, T., Tenenhouse, A., Poliquin, S., Berger, C., Joseph, L., Brown, J.P., Murray, T.M., Adachi, J.D., Hanley, D.A., and Papadimitropoulos, E.: Canadian normative data for the SF-36 health survey. Canadian multicentre osteoporosis study research group; CMAJ; 163; 265-271; 2000.