Renal physiology for the Primary FRCA

advertisement

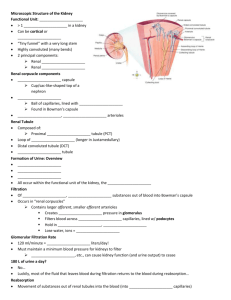

Notes on Renal Physiology for the Primary FRCA Dr Alison Chalmers Queen Victoria Hospital, East Grinstead Basic functions of the kidney 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Salt and water homeostasis Acid-base homeostasis Excretion of waste products, water soluble toxins and drugs Calcium and phosphate homeostasis Retention of vital substances e.g. Proteins and glucose Endocrine functions e.g. Production of erythropoietin Basic anatomy of the kidney ● ● ● The functional unit of the kidney is the nephron; each kidney contains 1-1.5 million nephrons. The kidney is unique in that it has two capillary beds arranged in series – the glomerular capillaries and the peritubular capillaries. Each nephron contains: ▪ A glomerulus consisting of a knot of capillaries which surround the blind ended pouch of the nephron (Bowman’s capsule) ▪ Proximal convoluted tubule ▪ Descending thin limb of the loop of Henle ▪ Ascending thin and thick limb of the loop of Henle ▪ Vasa recta – specialized capillaries which wrap around the loop of Henle ▪ Distal convoluted tubule ▪ Collecting duct ● The kidney is divided into the cortex and medulla. The majority of nephrons are located in the cortex with short loops of Henle extending a short way into the medulla. Juxtamedullary nephrons have their glomeruli in the inner cortex with long loops of Henle extending deep into the medulla. Renal blood flow ● ● ● ● ● 20% of the cardiac output goes to the kidneys which account for only 0.5% of the body weight. >90% enters via the renal artery to the cortex which is perfused at approx 500ml/min/100g tissue. Some of the cortical blood flow passes to the medulla – the outer part receives 100ml/min/100g, the inner medulla receives 20ml/min/100g. The renal artery branches into several interlobar arteries, then arcuate arteries, then interlobular arteries to form the afferent arterioles which give rise to the glomerular capillaries. These drain into the efferent arteriole which are portal vessels, draining from one capillary bed into a second – the peritubular capillaries surrounding the cortical tubules and the vasa recta wrapped around the loops of Henle. These eventually drain into the renal vein. The blood supply provides for the metabolic demands of the kidney, but also maintains glomerular filtration and provides oxygen for the active reabsorption of sodium. Renal blood flow is independent of the perfusion pressure between a mean pressure of 90-200mmHg – ‘autoregulation’. Both afferent and efferent arterioles can vasoconstrict, so as wall tension increases in the afferent arterioles vasoconstriction occurs maintaining constant blood flow. The renin-angiotensin system also plays a role in maintaining constant renal blood flow. Macula densa cells are specialized distal tubular epithelial cells in close proximity to the afferent and efferent capillaries. These cells and capillaries form the juxtaglomerular complex. When the blood pressure falls there is a subsequent fall in renal blood flow and filtrate volume, resulting in a decrease delivery of sodium and chloride to the macula densa cells in the distal tubule causing a local release of rennin. Renin is the enzyme that converts angiotensinogen to angiotensin I, which is then converted to angiotensin II in the lungs by ACE. Angiotensin II has four main effects: ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ● ● Generalised vasoconstriction → ↑ SVR ↑ BP Vasoconstriction of efferent arterioles to a greater extent than afferent arterioles in the kidney → ↑ GFR Release of aldosterone by adrenal → ↑ sodium and water retention Stimulates thirst by action on hypothalamus Renal plasma flow (RPF) is measured by clearance of para-aminohippuric acid. Renal blood flow = RPF x 100/55. Glomerular filtration ● ● ● ● ● ● ● The glomerulus is a knot of capillaries fed by an afferent arteriole and drained by an efferent arteriole. The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is approx 125ml/min; about 20% of renal blood flow is filtered as it passes through the glomerulus. Its function is to produce an ultrafiltrate of the plasma, which forms the basis of urine. The ultrafiltrate is formed by the process of filtration through the capillary bed which is dependent on the balance between hydrostatic and colloid osmotic pressure. The presence of a second capillary bed maintains a higher hydrostatic pressure (45mmHg) than in other simple capillary beds (32mmHg) favouring the movement of fluid into the capsule. The permeability of the glomerular capillary is 100x that of other capillaries. GFR α forces favouring filtration – forces opposing filtration Ie: GFR α (PG + ΠB) – (PB + ΠG) where PG is the hydrostatic pressure in the glomerular capillary, ΠB is the colloid osmotic pressure in Bowman’s capsule, PB is the hydrostatic pressure in Bowman’s capsule and ΠG is the colloid osmotic pressure in the glomerular capillary. The filtrate must pass through three layers from the capillary to capsule: the endothelial cell layer of the capillary, the glomerular basement membrane and the visceral epithelial cells of Bowman’s capsule. The filtration rate is higher for juxtaglomerular nephrons than cortical nephrons. The single nephron GFR is determined by the composition of the tubular fluid in the distal nephron, while the concentration is determined by the filtration rate. Clearance ● ● ● The clearance of any substance excreted by the kidney is the volume of plasma that is cleared of the substance in unit time. Inulin clearance – the measurement of GFR because it is freely filtered by the glomerulus but not reabsorbed, secreted, synthesized or metabolized by the kidney. Creatinine clearance is an alternative way of measuring GFR, although it is more of an estimate as it is secreted to some extent by the tubules. Para-aminohippuric acid (PAH) clearance – measurement of renal plasma flow. It is filtered by the glomerulus and secreted, and is therefore almost completely removed from the plasma by the kidneys. Tubular function and urine formation ● The function of the renal tubule is to selectively reabsorb approx 99% of the glomerular filtrate. The proximal convoluted tubule ● ● ● ● The proximal convoluted tubule reabsorbs 60% of all solute including 100% glucose and amino acids, 90% of bicarbonate, 80-90% of inorganic phosphate and water, and 40-50% urea. Solute transport occurs by four different mechanisms: ▪ Passive diffusion: movement of ions down an electrochemical gradient e.g. Sodium and chloride ▪ Facilitated diffusion: passive but selective as requires the interaction between an ion and membrane bound carrier protein e.g. Sodium/amino acid cotransporter ▪ Passive diffusion through a membrane channel or pore e.g. Potassium in the collecting duct ▪ Active transport: against an electrochemical gradient by energy requiring pump Some transporters in the proximal tubule are active or passive secreters of weak acids and bases e.g. Organic acids, strong organic bases such as histamine and choline. Sodium transport in the proximal tubule – 60% filtered reabsorbed ▪ Na+ entry into the tubule cells is a passive process down a electrochemical gradient ▪ Many other solutes are transported with Na+-linked symport and antiport systems mediated by carrier proteins; 80% Na+ entering the tubule cells does so in exchange for H+. In turn H+ secretion into the tubule cells leads to the reabsorption of both Cl- and HCO3▪ Na+K+ATPase actively extrudes Na+ against the gradients from the tubule cells into the lateral intercellular spaces to be peritubular capillaries – determined by the balance of colloid osmotic and hydrostatic pressure across the endothelium. ● ● ● ● Chloride: Cl- is absorbed from the proximal tubule into the tubule cells by antiport in exchange for organic anions such as bicarbonate, formate and oxalate, and in the late proximal tubule down its concentration gradient established by HCO3absorption. Bicarbonate: reabsorption occurs in the proximal tubule as a result of H+ secretion from tubular cells into the lumen. Water: 60% reabsorbed in the PT down concentration gradients established by ion gradients, and the existence of a hypertonic lateral intercellular space. Glucose: the amount of glucose filtered is directly proportional to the plasma glucose concentration. Glucose transport processes are saturated at a plasma glucose of 22mmol/l – a process called Tm-limited transport. Transport occurs with sodium – an example of symport transport where the movement of sodium down its concentration gradient generates energy for the movement of glucose against its concentration gradient, and so maintenance of the sodium gradient is essential for the absorption of glucose. Loop of Henle ● The role of the loop of Henle is to create an increasing concentration gradient in the interstitial tissues hence playing a vital role in the concentrating of urine as required. ● Utilises a counter current mechanism which occurs as different parts of the LOH have different permeabilities to sodium, chloride, potassium and water. ● Up to 50% of the medullary interstitial osmolality is due to urea which diffuses from the medullary collecting tubules under the influence of ADH. Distal convoluted tubule This is where the final fine tuning of the reabsorption of many ions is achieved. Collecting duct ● The collecting duct passes down through the interstitial concentration gradient generated by the loop of Henle. It is has variable permeability to water depending on the amount of ADH present. Achieves the final urine concentration. ● ADH – increases permeability of the collecting duct to water. Normal levels of ADH produce urine volumes of 1.5l/day, with an osmolality of 300500mosmol/kgH2O. When no ADH is present (diabetes insipidus) urine volumes are 23l/day with osmolality of 60mosmol/kgH2O. Adrenal steroids must be present for ADH to have its maximum effect on water permeability. Regulation of fluid and electrolyte balance ● ● Regulation of total body fluid volume is dependent on regulation of the ECF volume, which is mediated by osmoreceptors that affect ADH release. ADH is released from the posterior pituitary in response to: ▪ Increased osmolality in the hypothalamus ▪ Decreased plasma volume (cardiopulmonary receptors in right atrium and pulmonary vessels) ▪ Angiotensin II ● ● ● Osmoreceptors respond to changes in ECF osmolality – which is primarily determined by sodium and therefore control of body fluid volume is dependent on the control of body sodium content. Primary control of sodium reabsorption is mediated by the renin, angiotensin, aldosterone system (RAS) as discussed above. ▪ Aldosterone increases sodium reabsorption by increasing the number of sodium channels and pumps in the collecting ducts and distal tubules Overall regulation of sodium reabsorption is complex and also influenced by starling forces in the peritubular capillaries, neurological reflexes, renal prostaglandins, ANP and dopamine. ▪ ANP is released in response to atrial stretch, increasing sodium excretion by inhibiting the RAS and by direct inhibition of the reabsorption of sodium in the collecting duct Clinical examples ● Infusion of 1000mls 5% glucose ie water – causes plasma dilution and a decrease in osmolality, detected by osmoreceptors, and resultant decrease in ADH secretion resulting in a diuresis to remove excess water. ● Infusion of 1000mls blood ie large increase in intravascular volume – acutely stimulates the baroreceptors causing a reflex decrease in cardiac output and vascular tone mediated by the vagus and glossophayngeal nerves, more slowly causes a decrease in the RAS activity and decrease in aldosterone secretion, therefore reducing sodium and water reabsorption from the kidney. Angiotensinogen Na depletion Renin Decrease blood volume Angiotensin I ACE Decrease blood pressure Increase ADH Decrease ANP Angiotensin II Aldosterone Increase BP Na retention Increase blood vol Renal Regulation of acid base balance ● ● Bicarbonate is the most important buffer system throughout the body. A buffer solution limits the change of pH when an acid or base is added to it, hence its importance is maintaining the pH of the body within a narrow range. Bicarbonate is freely filtered at the glomerulus and 90% is reabsorbed in the proximal tubule, a process dependent on H+ secretion. H+ and HCO3- combine in the lumen to form H2CO3 which then dissociates into CO2 and H2O, a reaction catalysed by carbonic anhydrase. The CO2 diffuses into the tubular cell where the process is reversed to form HCO3- again. CO2 + H2O ≡ H2CO3 ≡ H+ + HCO3- ● ● H+ secretion is linked to Na+ entry into the proximal tubular cells and the luminal membrane also has a primary H+ secretory mechanism. The remaining 10% filtered bicarbonate is reabsorbed in the distal tubule and collecting duct in the same process as in the proximal tubule. Renal regulation of pH in acid base disturbances ● ● ● ● The rate of H+ secretion varies inversely with pH. Respiratory acidosis: ▪ ↑CO2 due to an underlying respiratory problem e.g. hypoventilation resulting in increased H+ production and an acidosis. ▪ Rate of H+ secretion in the kidney increases leading to increased bicarbonate reabsorption from the kidney and increased plasma bicarbonate. ▪ This is renal compensation for respiratory acidosis restoring the pH back towards normal. Respiratory alkalosis: ▪ ↓CO2 due to hyperventilation resulting in decreased H+ production and an alkalosis ▪ Rate of H+ secretion in the kidney decreases leading to decreased bicarbonate reabsorption and decreased plasma bicarbonate. ▪ This is renal compensation for respiratory alkalosis restoring the pH back towards normal. Metabolic acidosis: ▪ Can be due to production of extra acid eg ischaemic bowel which as a result also depletes plasma bicarbonate levels, or can be due to the loss of bicarbonate eg renal tubular acidosis. ▪ Respiratory compensation occurs as the change in pH is detected by peripheral chemoreceptors and ventilatory rate is increased lowering plasma H+ and raising the pH back towards normal. ▪ Renal correction then occurs as increased H+ secretion occurs in the renal tubule hence increasing reabsorption of all the filtered bicarbonate. Micturition ● The smooth muscle of the bladder is the detrusor muscle. Two sphincters oppose the emptying of the bladder ▪ Incomplete ring of smooth muscle around urethra – internal sphincter ▪ Complete ring of skeletal muscle – external sphincter ● Process of micturition is a spinal reflex with learned ability to control bladder emptying References 1. Pinnock C, Lin T and Smith T. Fundamentals of Anaesthesia 2nd Edition - Section 2:7 Renal physiology by CJ Lote 2. Wallace K. Renal Physiology. Update in Anaesthesia. www.worldanaesthesia.org