Exploring strategies developed by parents to

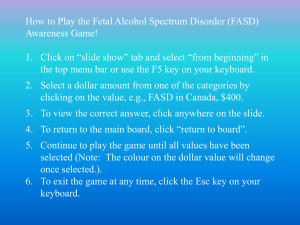

advertisement