Mindfulness meditation Research findings

advertisement

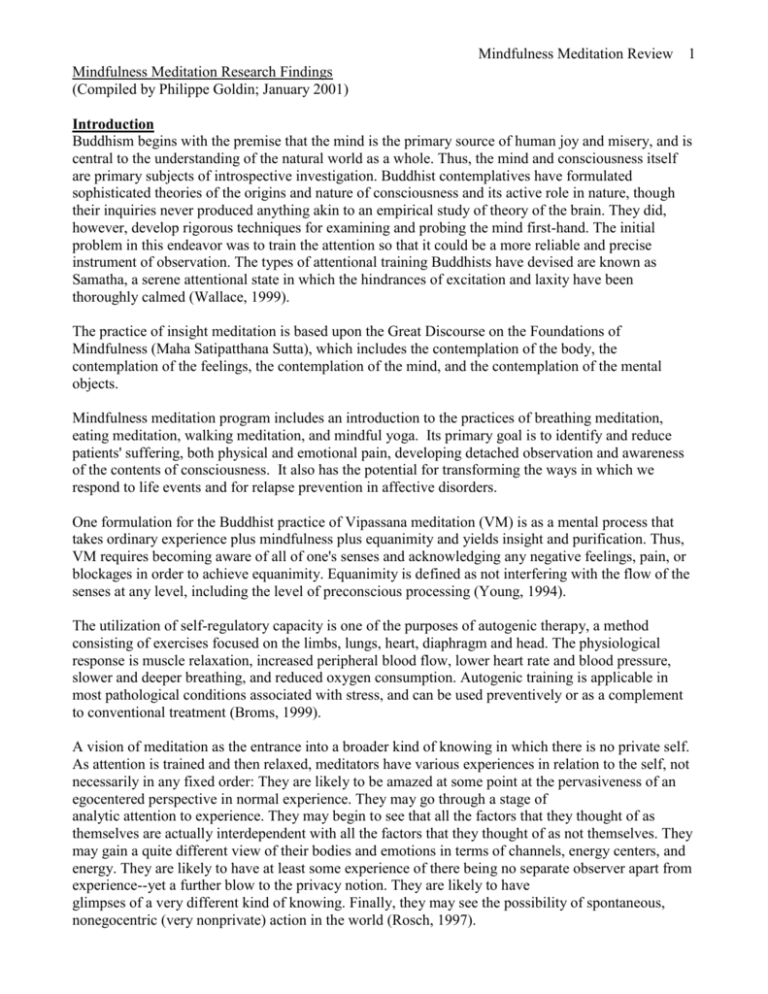

Mindfulness Meditation Review 1 Mindfulness Meditation Research Findings (Compiled by Philippe Goldin; January 2001) Introduction Buddhism begins with the premise that the mind is the primary source of human joy and misery, and is central to the understanding of the natural world as a whole. Thus, the mind and consciousness itself are primary subjects of introspective investigation. Buddhist contemplatives have formulated sophisticated theories of the origins and nature of consciousness and its active role in nature, though their inquiries never produced anything akin to an empirical study of theory of the brain. They did, however, develop rigorous techniques for examining and probing the mind first-hand. The initial problem in this endeavor was to train the attention so that it could be a more reliable and precise instrument of observation. The types of attentional training Buddhists have devised are known as Samatha, a serene attentional state in which the hindrances of excitation and laxity have been thoroughly calmed (Wallace, 1999). The practice of insight meditation is based upon the Great Discourse on the Foundations of Mindfulness (Maha Satipatthana Sutta), which includes the contemplation of the body, the contemplation of the feelings, the contemplation of the mind, and the contemplation of the mental objects. Mindfulness meditation program includes an introduction to the practices of breathing meditation, eating meditation, walking meditation, and mindful yoga. Its primary goal is to identify and reduce patients' suffering, both physical and emotional pain, developing detached observation and awareness of the contents of consciousness. It also has the potential for transforming the ways in which we respond to life events and for relapse prevention in affective disorders. One formulation for the Buddhist practice of Vipassana meditation (VM) is as a mental process that takes ordinary experience plus mindfulness plus equanimity and yields insight and purification. Thus, VM requires becoming aware of all of one's senses and acknowledging any negative feelings, pain, or blockages in order to achieve equanimity. Equanimity is defined as not interfering with the flow of the senses at any level, including the level of preconscious processing (Young, 1994). The utilization of self-regulatory capacity is one of the purposes of autogenic therapy, a method consisting of exercises focused on the limbs, lungs, heart, diaphragm and head. The physiological response is muscle relaxation, increased peripheral blood flow, lower heart rate and blood pressure, slower and deeper breathing, and reduced oxygen consumption. Autogenic training is applicable in most pathological conditions associated with stress, and can be used preventively or as a complement to conventional treatment (Broms, 1999). A vision of meditation as the entrance into a broader kind of knowing in which there is no private self. As attention is trained and then relaxed, meditators have various experiences in relation to the self, not necessarily in any fixed order: They are likely to be amazed at some point at the pervasiveness of an egocentered perspective in normal experience. They may go through a stage of analytic attention to experience. They may begin to see that all the factors that they thought of as themselves are actually interdependent with all the factors that they thought of as not themselves. They may gain a quite different view of their bodies and emotions in terms of channels, energy centers, and energy. They are likely to have at least some experience of there being no separate observer apart from experience--yet a further blow to the privacy notion. They are likely to have glimpses of a very different kind of knowing. Finally, they may see the possibility of spontaneous, nonegocentric (very nonprivate) action in the world (Rosch, 1997). Mindfulness Meditation Review 2 Stress & Psychopathology An 8-wk meditation-based stress reduction on 73 premedical and medical students showed using an intervention group and a wait-list control group that the intervention can effectively (1) reduce selfreported state and trait anxiety, (2) reduce reports of overall psychological distress including depression, (3) increase scores on overall empathy levels, and (4) increase scores on a measure of spiritual experiences assessed at termination of intervention. These results (5) replicated in the wait-list control group, (6) held across different experiments, and (7) were observed during the exam period. Measures included an adapted version of the Empathy Construct Rating Scale, the Hopkins Symptom Checklist 90 (Revised), the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y), and the Index of Core Spiritual Experiences (Shapiro et al., 1998). 42 adolescent boys residing in a camp for juvenile delinquents were separated into two groups that participated in (reverse order) an eight-week meditation program condition that taught progressive relaxation, concentration techniques, and mindfulness meditation and an eight-week video/discussion group condition. There was a significant reduction in anxiety and an increase in internal locus of control (as measured by the Brief Symptom Inventory and Pugh's Prison Locus of Control Scale) after participation in the meditation program, with no changes in the video/discussion control condition (Flinton, 1998). 19 beginning and 24 advanced Buddhist mindfulness meditators (all Subjects aged 24-64 yrs) received daily random electronic page signals for 5 days and responded by completing an Experience Sampling form. As compared with beginners, advanced practitioners reported greater self-awareness, positive mood, and acceptance. Greater stress lowered mood and self-acceptance in both groups, but the deleterious effect of stress on acceptance was more marked for the beginners (Easterlin & Cardena, 1998-1999). 24 college students learned either a meditation or a cognitive self-observation procedure for 3 consecutive training sessions and practiced the method daily. Both groups showed reliable increases in dimensions of self-actualization (measured by the Personal Orientation Inventory) and decreases in common stress-related symptoms (measured by the Symptoms of Stress Inventory). There were no differential treatment effects (Greene & Hiebert, 1988). Concentration meditation and mindfulness meditation have differential effects related to the process of unveiling past trauma or emotions during meditation practices, and may actually temporarily increase the stress level for some people (Miller, 1993). Mindfulness mediation has been implemented with approximately 200 patients presented in English and Spanish in an inner-city setting (Ruth, 1997). Mindfulness and concentrative meditation techniques have been employed for understanding, management, and prevention of anger (Barbieri, 1997). An experimental group of 100 meditators and a control group of 50 non-meditators in Chiangmai, Thailand participated were assessed pre/post vipassana mediation retreat. Results demonstrated that compared to the control group, participants in the meditation program showed reduced levels of psychopathology based on the following SCL-90-R variables: obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. Somatization did not appear to be affected by the meditation treatment. Gender did not appear to moderate the treatment effect (Disayavanish, 1995). Mindfulness Meditation Review 3 31 male inmates with alcohol abuse and aggression ranging in age from 17 to 46 were randomly assigned to six two hour treatment sessions training in Mindfulness Meditation (MM) or Progressive Relaxation Training (PRT). The sample consisted of 31 male inmates ranging in age from 17 to 46. There were non-significant reductions in self-reported anger (State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory) and impulsivity (Porteus Maze Test). However, a significant within group post-stressor (mental arithmetic) reduction in cortisol levels was found in the PRT group only (20 vs. 40 min, p =.026), and (20 vs. 60 min, p =.028). A statistically significant between group differences favoring MM were found on a sub-measure of egocentrism called negative self-focused attention (p =.008). One month follow up revealed a slight increase in aggressive responding in the PRT group and a slight decrease in the MM group (Murphy, 1995). Significant clinical improvements in symptoms of anxiety and panic following an 8-week stress reduction and relaxation program were found in a pilot study of 22 medical outpatients who met DSMIII-R diagnosis for generalized anxiety or panic disorder with or without agoraphobia. Improvements were identified in patient’s self-rating scores of anxiety and depression (Beck anxiety and depression scales) and in interviewer’s ratings (Hamilton anxiety and depression scales) (Kabat-Zinn, et al. 1992). Three year follow-up of 18 medical outpatients with anxiety disorders who showed improvements in subjective and objective symptoms of anxiety and panic following an 8-wk outpatient group stress reduction intervention based on mindfulness meditation showed maintenance of the gains obtained in the original study on depression and anxiety scales as well as on the number and severity of panic attacks. Ongoing compliance with the meditation practice was also demonstrated in the majority of Subjects at 3 yrs (Miller, Fletcher, Kabat-Zinn, 1995). 28 undergraduates were randomized into either an experimental group or a nonintervention control group. Experimental subjects, when compared with controls, evidenced significantly greater changes in terms of (1) reductions in overall psychological symptomatology; (2) increases in overall domainspecific sense of control and utilization of an accepting or yielding mode of control in their lives; and (3) higher scores on a measure of spiritual experiences. The intervention participants showed a mean reduction of 64% on the SCL-90-R (Derogatis, 1983) overall psychological distress score from pre to post treatment (Astin, 1997). 20 patients (with Axis I & II disorders) undergoing private, long-term individual exploratory psychotherapy participated in a ten-week mindfulness meditation program demonstrated significant decreases on psychological symptoms from pre to post intervention, with the largest decreases noted in depression and anxiety. Daily chores, social activities, and work were reported to be easier to perform after the intervention, and significantly less interference of stress and pain in daily activities were also reported. Ratings from the clients’ therapists confirmed the improvement in their clients’ psychological well-being and insight. (Kutz et al., 1985). Meditation as an adjunct to psychotherapy 20 patients (mean age 38 yrs) undergoing long-term (from 1 to 10 yrs) individual dynamic-explorative psychotherapy participated in a 10-wk group meditation program. Significant improvements in the well-being of subjects as rated by themselves and their individual psychotherapists. Subjects and therapists identified similar areas of improvement, such as anxiety and depression. Therapists reported marked improvement in the development of insight. Results indicate that meditation can be an important adjunct to psychotherapy (Kutz et al., 1985). Mindfulness Meditation Review 4 Depressive Relapse Prevention Preventive interventions operate by changing the patterns of cognitive processing that become active in states of mild negative affect. From this perspective, training in the redeployment of attention is relevant to preventing depressive relapse (Teasdale, Segal, & Williams, 1995). Fibromyalgia 77 patients with fibromyalgia participating in a 10-wk mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program showed improvement on measures of global well-being, pain, sleep, fatigue, and the experience of feeling refreshed in the morning, medical symptom checklist, psychiatric symptoms (SCL-90 Revised), coping strategies, fibromyalgia impact, and attitudes toward fibromyalgia (Kaplan, Goldenberg, & Galvin-Nadeau, 1993). Smoking Cessation Thirty-nine cigarette smokers from an electronics company in the Northeast were randomly assigned into one of two experimental groups: group 1 received mindfulness meditation and cognitive behavioral intervention and group 2 received only cognitive-behavioral interventions. Measurements were obtained at four distinct time periods. Nonsignificant differences were found between the groups on the major outcome measures. Subjects, regardless of group membership, demonstrated significantly lower nicotine, depression, distress, and number of cigarettes smoked at Time 4 (Arcari, 1997). Cancer After the 7 weeks intervention, 90 patients (aged 27-75 yrs) patients in the treatment group had significantly lower scores on Total Mood Disturbance and subscales of Depression, Anxiety, Anger, and Confusion and more Vigor than control Subjects. The treatment group also had fewer overall Symptoms of Stress; fewer Cardiopulmonary and Gastrointestinal symptoms; less Emotional Irritability, Depression, and Cognitive Disorganization; and fewer Habitual Patterns of stress. Overall reduction in Total Mood Disturbance was 65%, with a 31% reduction in Symptoms of Stress (Speca et al., 2000). For 18 cancer patients who volunteered for a 9-week mindfulness meditation course experiences of cancer and mindfulness meditation practice fell into 5 broad categories: (a) Cancer: A Catalyst for Inner Exploration; (b) Mindfulness Meditation: A Way of Inner Exploration; (c) Mindfulness in Routine Activities; (d) Mindfulness in Self-Understanding; and (e) Mindfulness in Interpersonal Relationships. The study revealed that for many of the participants a diagnosis of cancer had stimulated an interest in inner exploration, for which mindfulness became a disciplined approach that helped them understand and enrich their lives. They described how bringing an accepting awareness to daily routine enhanced their self-knowledge, making them aware of and more prone to attend to their needs. They also became conscious of the good moments still available to them. In addition, the participants reported that bringing nonjudgmental awareness to stressful interactions with others gave them greater control over their feelings and behavior, enabling them to develop more appropriate modes of communication (Young, 1999). Melatonin may be related to a variety of biologic functions important in maintaining health and preventing disease, including breast and prostate cancer. A study of urinary 6-sulphatoxymelatonin in 8 women who regularly meditate (RM) and 8 women who do not meditate (NM) demonstrated that regular practice of mindfulness meditation is associated with increased physiological levels of melatonin (Massion et al., 1995). Mindfulness Meditation Review 5 Cognitive Processing Sustained attention: performance by 19 meditators demonstrated superior performance on the test of sustained attention in comparison with controls, and long-term meditators were superior to short-term meditators. Mindfulness meditators showed superior performance in comparison with concentrative meditators when the stimulus was unexpected but there was no difference between the two types of meditators when the stimulus was expected (Valentine & Sweet, 1999). 73 residents of 8 homes for the elderly (mean age = 81 years) were randomly assigned among no treatment and 3 treatments highly similar in external structure and expectations: the Transcendental Meditation (TM) program, mindfulness training (MF) in active distinction making, or a relaxation (low mindfulness) program. A planned comparison indicated that the "restful alert" TM group improved most, followed by MF, in contrast to relaxation and no-treatment groups, on paired associate learning; 2 measures of cognitive flexibility; word fluency; mental health; systolic blood pressure; and ratings of behavioral flexibility, aging, and treatment efficacy. The MF group improved most, followed by TM, on perceived control. After 3 years, survival rate was 100% for TM and 87.5% for MF in contrast to lower rates for other groups (Alexander et al., 1989). Tested visual sensitivity differences, using tachistoscopic presentation of light flashes, in 39 practitioners (in 3 groups) of Buddhist mindfulness meditation and 10 nonmeditator controls. Meditation practitioners were able to detect light flashes of shorter duration than the nonmeditators. There were no differences among practitioner and control groups in ability to discriminate between closely spaced successive light flashes. It is suggested that lower detection threshold for single light flashes reflects an enduring increase in sensitivity, perhaps the long-term effects of the practice of meditation on certain perceptual habit patterns. It is further suggested that the lack of differences in the discrimination of successive light flashes reflects the resistance of other perceptual habit patterns to modification (Brown, Forte, & Dysart, 1984). Chronic Pain 64 participants were assigned to one of the 3 groups (a cognitive-behavioral intervention (Philips & Rachman, 1996), a mindfulness based stress reduction intervention (Kabat-Zinn, 1990), and an attention-placebo control for chronic pain management) for 8 weekly sessions. Of 64 individuals with chronic pain who participated in this study, 39 completed the intervention program. When comparing the efficacy of mindfulness meditation with cognitive behavioral therapy, only participants in the mindfulness meditation condition significantly improved on the Somatization dimension and Positive Symptom Distress Index of the SCL-90, as well as on the Interference and Affective Distress scales of the Multidimensional Pain Inventory. Thus, the mindfulness meditation group improved on more dependent measures (McGill Pain Questionnaire, the Roland and Morris Disability Questionnaire, the Global Severity Index, the Positive Symptom Distress Index, as well as the Somatization and Anxiety dimensions of the SCL-90) than the cognitive behavioral and attentionplacebo groups (Bruckstein, 1999). 90 chronic pain patients underwent a 10-week mindfulness based stress reduction program and 21 chronic pain patients were treated with pain-medication without any form of self-regulation. The findings revealed significant improvement, compared to the comparison group, in present-moment pain, negative body-image, degree of inhibition of everyday activities by pain, medical symptoms, and psychological symptomatology including somatization, anxiety, depression, and self-esteem. Furthermore, pain related drug utilization decreased and activity levels increased. Improvements seemed to be independent of gender, source of referral, and type of pain. At follow-up, the recovery observed during the meditation training was maintained up to 15 months after the 10-week meditation training for all measures except present-moment pain (Kabat-Zinn, Lipworth, & Burney, 1985). Mindfulness Meditation Review 6 51 chronic pain patients engaged in a 10-week mindfulness based relaxation program. Subjects showed a reduction of 33% in the mean total of a pain rating index. Large and significant reductions in mood disturbance and psychiatric symptomatology accompanied these changes and were relatively stable up to 1.5 yrs later (Kabat-Zinn, 1984). Binge Eating Disorder The efficacy of a 6-week meditation-based group intervention for Binge Eating Disorder (BED) was evaluated in 18 obese women, using standard and eating-specific mindfulness meditation exercises. A single-group extended baseline design assessed all variables at 3 weeks pre- and post-intervention, and followed up at 1, 3, and 6 weeks. Briefer assessment occurred weekly. Binges decreased in frequency, from 4.02/week to 1.57/week, and in severity. Scores on the Binge Eating Scale (BES) and on the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories decreased significantly; sense of control increased. Time using eating-related meditations predicted decreases on the BES (Kristeller & Hallett, 1999). Skin Disorders 37 Subjects undergoing treatment for psoriasis were randomly assigned to mindfulness meditationbased stress reduction intervention guided by audiotaped instructions during light treatments, or a control condition consisting of the light treatments alone with no taped instructions. Four sequential indicators of skin status were monitored during the study: First Response, Turning, Halfway, and Clearing Points. Results show that subjects in the tape groups reached the Halfway Point and the Clearing Point significantly more rapidly than those in the no-tape condition, for both UVB and PUVA treatments (Kabat-Zinn et al., 1998). Dialogue between cognitive science and Buddhist meditation techniques “The existential concern that animates our entire discussion in this book results from the tangible demonstration within cognitive science that the self or cognizing subject is fundamentally fragmented, divided, or nonunified.... Our view is that the current style of investigation is limited and unsatisfactory, both theoretically and empirically, because there remains no direct, hands-on, pragmatic approach to experience with which to complement science....” (Varela, Thompson, & Rosch, 1991). Brain Imaging & EEG Signal Processing FMRI: Practice of meditation activates neural structures involved in attention and control of the autonomic nervous system, including significant signal increases in the dorsolateral prefrontal and parietal cortices, hippocampus/parahippocampus, temporal lobe, pregenual anterior cingulate cortex, striatum, and pre- and post-central gyri during meditation (Lazar et al., 2000). PET: Cerebral blood flow distribution (15O-H20 PET) were investigated in nine young adults, who were highly experienced yoga teachers, during the relaxation meditation (Yoga Nidra), and during the resting state of normal consciousness. During meditation differential activity was seen, with the noticeable exception of V1, in the posterior sensory and associative cortices known to participate in imagery tasks. In the resting state of normal consciousness (compared with meditation as a baseline), differential activity was found in dorso-lateral and orbital frontal cortex, anterior cingulate gyri, left temporal gyri, left inferior parietal lobule, striatal and thalamic regions, pons and cerebellar vermis and hemispheres, structures thought to support an executive attentional network (Lou et al, 1999). Mindfulness Meditation Review 7 EEG: Electroencephalographic recordings from 19 scalp recording sites in 10 Subjects (9 right- and one lefthanded) were used to differentiate among two posited unique forms of meditation, concentration and mindfulness, and a normal relaxation control condition. Subjects were tested after minimal meditation training, and after extensive training. During each recording session, Subjects performed 3 tasks: an eyes-closed relaxed baseline, a concentration mediation, and a mindfulness mediation. Analysis of all traditional frequency bandwidth data (i.e., delta, 1-3 Hz; theta, 4-7 Hz; alpha, 8-12 Hz; beta 1, 13-25 Hz; beta 2, 26-32 Hz) showed strong mean amplitude frequency differences between the two meditation conditions and relaxation over numerous cortical sites. Significant differences were obtained between concentration and mindfulness states at all bandwidths. Results suggest that concentration and mindfulness "meditations" may be unique forms of consciousness and are not merely degrees of a state of relaxation (Dunn et al., 1999). Comparison between Mindfulness Meditation and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy The mindfulness approach used in Kabat-Zinn’s stress and relaxation program shares some attributes with both cognitive and behavioral therapeutic approaches used primarily to treat anxiety and mood disorders. There are also some critical differences, both structurally and theoretically. Similarities: Mindfulness meditation and cognitive-behavioral therapy share skepticism in terms of relying on one’s thoughts as truths and proofs of reality, and encourage examination of thoughts, sensations, perceptions, and behavior. They emphasize noting sensations and thoughts without viewing them as catastrophic or depressive, and a stress-inducing situation is often considered a cue to engage in new behaviors. Mindfulness meditation and cognitive-behavioral therapy both accentuate cognitions as mediators of emotion, namely, emotional disturbance is caused by thoughts and cognitions that are “mental events” and not “realities.” Both approaches also subscribe to methods of cognitive restructuring (although different kinds) and homework assignments as an important aspect of the therapeutic work, and they encourage active, collaborative involvement from the client on the path toward recovery. Differences: In cognitive therapy, emphasis is placed on positive, negative, or faulty thoughts. In mindfulness meditation, however, the emphasis is on identifying thoughts as just “thoughts,” whether they be positive or negative, while acknowledging the potential inaccuracy and limits of all thoughts and not just thoughts that are depressogenic or cause anxiety. This attitude is cultivated both during formal meditation sessions and in the informal practices throughout the day. The two approaches differ in terms of the causal mechanisms of psychopathology and the extent to which the methods of remedy can be generalized. In the mindfulness approach, the emphasis is on meditation as a way of being and living one’s life, as well as a way to develop alternative, “generic” strategies for coping with stress, sadness, and pain, rather than as a technique for coping with a specific problem such as depression. The formal and informal meditation practices are meant to be applied daily regardless of one’s state of anxiety or affect. Philosophically, there is a major gap between the two traditions. An individual does not need to meat criteria for a specific disorder or disease in order to benefit from the mindfulness meditation. From a spiritual point of view, mindfulness meditation is considered to be a tool within a larger program aimed at eliminating all suffering in life, and, thus, whether psychologically healthy or not, every human being is hypothesized to gain from practicing mindfulness meditation. Cognitivebehavioral therapy, on the other hand, was developed as a treatment for individuals with psychopathology, and does not make any claims to be beneficial for every human being. It is important to mention, however, that Kabat-Zinn’s mindfulness meditation program is not affiliated with any religious order, even though it originates from a spiritual tradition, Vipassana, which in turn emanated from Buddha’s teachings. The mindfulness interventions so far have generally involved a heterogeneous group of patients with a range of medical and psychological problems. Cognitive-behavioral therapy is typically Mindfulness Meditation Review 8 provided to individuals or groups of people with a single disorder. Furthermore, in mindfulness training the intervention focuses on the meditation practice itself rather than on a specific disorder, diagnosis, or combination of symptoms. There is no attempt at systematic desensitization through the induction of symptoms during the mindfulness intervention. Although not intentionally evoked, when a stressful sensation or thought arises, either during formal meditation or in the course of daily living, patients are encouraged to see it as opportunities to engage in mindful coping strategies, to observe the thoughts, emotions and sensations as they arise and disappear, and to act instead of react according to habitual and thoroughly ingrained cognitive and behavioral patterns. The observational skills cultivated through mindfulness training differ considerably from those developed by behavioral monitoring techniques. As described above, participants in the program are trained initially to develop concentration or one-pointed attention by focusing on the breath. Concentration is assumed to help improve the ability to observe fearful or negative thoughts, sensations, and feelings in a nonreactive way. For instance, by being able to focus on the impermanent nature of thoughts, their rising and falling, a psychological buffer can be created between the person experiencing the thoughts and the thoughts themselves, thereby enhancing the probability for a less biased response as opposed to a habitual, and often dysfunctional, reaction. Coupled with mindfulness, concentration is hypothesized to give rise to a nonanalytical and direct experiencing of the object of attention, which can be contrasted to the external data collection involved in behavioral analysis of antecedents and consequences. Mindfulness Meditation Review 9 References Alexander, CN, Langer, EJ, Newman, RI, Chandler, HM, and others. (1989). Transcendental Meditation, mindfulness, and longevity: An experimental study with the elderly. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 57, 950-964. Arcari, Patricia Martin (1997). Efficacy of a workplace smoking cessation program: Mindfulness meditation vs cognitive-behavioral interventions. Boston Coll, USA,UMI Order number: AAM9707883 Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences & Engineering. 1997 Apr. 57 (10-B): p. 6174. Astin, J.A. (1997). Stress reduction through mindfulness meditation: Effects on psychological symptomatology, sense of control, and spiritual experiences. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 66, 97-106. Atwood, J. D., & Maltin, L. M. (1991). Putting Eastern Philosophies into western psychotherapies. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 3, 368-382. Barbieri, P (1997). Habitual desires: The destructive nature of expressing your anger. International Journal of Reality Therapy, 17, 17-23. Bogart, G. (1991). The use of meditation in psychotherapy: A review of the literature. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 3, 383-412. Broms, C. (1999). Free from stress by autogenic therapy. Relaxation technique yielding peace of mind and self-insight. Lakartidningen, 96(6):588-92. Brown, Daniel P.; Engler, Jack (1980). The stages of mindfulness meditation: A validation study. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 12, 143-192. Brown, Daniel; Forte, Michael; Dysart, Michael (1984). Differences in visual sensitivity among mindfulness meditators and non-meditators. Perceptual & Motor Skills, 58, 727-733. Brown, Daniel; Forte, Michael; Dysart, Michael (1984). Visual sensitivity and mindfulness meditation. Perceptual & Motor Skills, 58, 775-784. Brown, Daniel; Forte, Michael; Rich, Philip; Epstein, Gerald (1982-83). Phenomenological differences among self hypnosis, mindfulness meditation, and imaging. Imagination, Cognition & Personality, 2, 291-309. Bruckstein, DC (1999). Effects of acceptance-based and cognitive behavioral interventions on chronic pain management. Hofstra U, US,UMI Order number: AAM9919162 Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences & Engineering. 1999 Jul. 60 (1-B): p. 0359. Davidson, RJ, & Goleman, DJ (1977). The role of attention in meditation and hypnosis: A psychobiological perspective on transformations of consciousness. International Journal of Clinical & Experimental Hypnosis, 25, 291-308. Mindfulness Meditation Review 10 Disayavanish, Primprao The effect of buddhist insight meditation on stress and anxiety. Illinois State U, USA,UMI Order number: AAM9510422 Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities & Social Sciences. 1995 May. 55 (11-A): p. 3540. Dunn, BR, Hartigan, JA, & Mikulas, WL (1999). Concentration and mindfulness meditations: Unique forms of consciousness? Applied Psychophysiology & Biofeedback, 24, 147-165. Easterlin, B., & Cardena, E. (1998-1999). Cognitive and emotional differences between short- and long-term Vipassana meditators. Imagination, Cognition & Personality, 18, 69-81. Flinton, CA (1998). The effects of meditation techniques on anxiety and locus of control in juvenile delinquents. California Inst of Integral Studies, USA, UMI Order number: AAM9824353 Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences & Engineering.. 59 (2-B): p. 871. Forte, Michael; Brown, Daniel P.; Dysart, Michael (1987-1988). Differences in experience among mindfulness meditators. Imagination, Cognition & Personality, 7, 47-60. Goleman, D. (1988). The Meditative Mind: The Varieties of Meditative Experience. New York: Penguin Greene, YN, & Hiebert, B (1988). A comparison of mindfulness meditation and cognitive selfobservation. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 22, 25-34. Kabat-Zinn, J. (1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical Considerations and preliminary results. General Hospital Psychiatry, 4, 33-47. Kabat-Zinn, J. (1984). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. ReVISION, 7, 71-72. Kabat-Zinn. J (1990). Full catastrophy living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Delacorte. Kabat-Zinn, et al. (1992). Kabat-Zinn, J., Lipworth, L., & Burney, R. (1985). The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 8 (2), 163-190. Kabat-Zinn, J., Wheeler, E., Light, T., Skillings, A., Scharf, M. J., Cropley, T. G., Hosmer, D., & Bernhard, J. D. (1998). Influence on mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction intervention on rates of skin clearing patients with moderate to severe psoriasis undergoing phototherapy (uvb) and photochemotherapy (puva). Psychosomatic Medicine, 60, 625-632. Kaplan, KH, Goldenberg, DL, & Galvin-Nadeau, M (1993). The impact of a meditation-based stress reduction program on fibromyalgia. General Hospital Psychiatry, 15, 284-289. Khalsa, Sat-Kaur Effects of two types of meditation on self-esteem of introverts and extraverts. U California, Berkeley, USA, Dissertation Abstracts International. 1991 Mar. 51 (9-A): p. 3018. Mindfulness Meditation Review 11 Kornfield, Jack M. The psychology of Mindfulness Meditation. Saybrook Inst, Dissertation Abstracts International. 1983 Aug. 44 (2-B): p. 610. Kristeller, J.L., & Hallett, C.B. (1999). An exploratory study of a meditation-based intervention for binge eating disorder. Journal of Health Psychology, 4, 357-363. Kutz, I., Borysenko, J. Z., & Benson, H. (1985). Meditation and psychotherapy: a rationale for the integration of dynamic psychotherapy, the relaxation response, and mindfulness meditation. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 142, 1-8. Kutz, I., Leserman, J., Dorrington, C., Morrison, C. H., Borysenko, J. Z., & Benson, H. (1985). Meditation as an adjunct to psychotherapy: An outcome study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 43, 209-218. Lazar, SW, Bush, G, Gollub, RL, Fricchione, GL, Khalsa, G, & Benson, H. (2000). Functional brain mapping of the relaxation response and meditation. Neuroreport, 11, 1581-5. Lou, HC, Kjaer, TW, Friberg, L, Wildschiodtz, G, Holm, S, & Nowak, M. (1999). A 15O-H2O PET study of meditation and the resting state of normal consciousness. Human Brain Mapping, 7, 98-105. Marlatt, G.A., & Kristeller, J.L. (1999). Mindfulness and meditation. In: William R. Miller, Ed; et al. Integrating spirituality into treatment: Resources for practitioners.. American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. p. 67-84 of xix, 293pp. Massion, AO; Teas, J; Hebert, JR; Wertheimer, MD; Kabat-Zinn, J. (1995). Meditation, melatonin and breast/prostate cancer: hypothesis and preliminary data. Medical Hypotheses, 44, 39-46. Miller, John J. (1993). The unveiling of traumatic memories and emotions through mindfulness and concentration meditation: Clinical implications and three case reports. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 25, 169-180. Miller, JJ, Fletcher, K, & Kabat-Zinn, J (1995). Three-year follow-up and clinical implications of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction intervention in the treatment of anxiety disorders. General Hospital Psychiatry, 17, 192-200. Murphy, Robert (1995). The effects of mindfulness meditation vs progressive relaxation training on stress egocentrism anger and impulsiveness among inmates. Hofstra U, USA,UMI Order number: AAM9501855 Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences & Engineering. 1995 Feb. 55 (8-B): p. 3596. Rosch, Eleanor (1997). Mindfulness meditation and the private (?) self. In: Ulric N., Ed; D.A. Jopling, Ed; et al. The conceptual self in context: Culture, experience, self-understanding.. Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. p. 185-202 of viii, 285pp. Roth, B. (1997). Mindfulness-based stress reduction in the inner city. Advances, 13, 50-58. Santorelli, Saki Frederic (1993). A qualitative case analysis of mindfulness meditation training in an outpatient stress reduction clinic and its implications for the development of self-knowledge. U Massachusetts, USA, Dissertation Abstracts International. 1993 Mar. 53 (9-A): p. 3115. Mindfulness Meditation Review 12 Shapiro, S.L., Schwartz, G.E., & Bonner, G. (1998). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on medical and premedical students. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 21, 581-599. Siebert, James Robert (1994). Meditation, absorption, and anxiety: Predisposition and training effects. California Inst of Integral Studies, CA, USA, Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences & Engineering. 1994. 55 (3-B): p. 1193. Speca, Michael; Carlson, Linda E.; Goodey, Eileen; Angen, Maureen (2000). A randomized, wait-list controlled clinical trial: The effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62, 613-622. Tate, David Brent (1994). Mindfulness meditation group training: Effects on medical and psychological symptoms and positive psychological characteristics. Brigham Young U, UT, USA, Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences & Engineering. 1994. 55 (5-B): p. 2018. Teasdale, J. D., Segal, Z., & Williams, J. M. G. (1995). How does cognitive therapy prevent depressive relapse and why should attentional control (mindfulness) training help? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33 (1), 25-39. Valentine, Elizabeth R.; Sweet, Philip L. G. (1999). Meditation and attention: A comparison of the effects of concentrative and mindfulness meditation on sustained attention. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 2, 59-70. Varela, Francisco J.; Thompson, Evan; Rosch, Eleanor (1991). The embodied mind: Cognitive science and human experience. The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. xx, 308pp. Wallace, B.A. The cultivation of sustained voluntary attention in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism. Stanford U, USA,UMI Order number: AAM9535686 Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities & Social Sciences. 1995 Dec. 56 (6-A): p. 2286 Wallace, B.A. (1999). The Buddhist tradition of Samatha: Methods for refining and examining consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 6, 175-187. Young, R.P. (1999). The experiences of cancer patients practicing mindfulness meditation. Saybrook Inst., US,UMI Order number: AEH9925005 Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences & Engineering. 1999 Oct. 60 (4-B): p. 1508. Young, Shinzen (1994). Purpose and method of Vipassana meditation. Humanistic Psychologist, 22, 53-61. Mindfulness Meditation Review 13 Wiveka Ramel's study: The Effect of Mindfulness Meditation Training on Cognition and Mood/Anxiety Symptoms Study: Canadian and British clinical/cognitive psychology researchers have proposed that mindfulness meditation is a systematic method of enhancing attentional allocation, deployment and response control, thereby establishing an alternative form of processing information. Training in attentional deployment may be useful in early detection and redirection of habitual tendencies that typically risk escalating harmful patterns of thought and behavior. The primary goals of this study are to (a) investigate whether an eight-week training program in mindfulness meditation enhances attentional control and reduces judgment bias- particularly in patients with a history of mood or anxiety disorders- as measured by two information-processing tasks, (b) examine if mindfulness meditation improves cognitive functioning of self-schemas as measured by self-report measures on rumination and dysfunctional attitudes, and (c) replicate and extend previous findings on the effect of mindfulness training on reducing symptoms in the area of anxiety, depression, and general health. Participants will be assessed at treatment intake and end of treatment diagnostically (SCID) and on measures of selective attention, memory for faces, depression, anxiety, and general health symptoms. About 20 veterans have already completed the study at pre and posttest up to this point. Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR) Program: The MBSR program is an 8-week course introducing the participants to the process of mindfulness meditation and focused body movements such as yoga. Mindfulness can be defined as paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally. One of the goals of mindfulness meditation is to provide an alternative mode of relating to, or experiencing, thoughts, emotions, physical sensations, and events in the environment by learning how to become aware of, observe and accept inner and outer phenomena without judgment. Mindfulness training involves using one’s attention to maintain awareness on a designated object, such as the breath or physical sensations in the body, without isolating other aspects of internal and external events. Previous research has shown that the MBSR course is an effective form of treatment for stress and worry in general, anxiety disorders, pain, and skin related diseases. In addition, it has been shown to be an effective complement to traditional forms of psychotherapy and to prevent relapse of clinical depression. Mindfulness Meditation Review 14 The Effects of Stress: Biological Effects The chemical effects of stress in the brain and in the body are powerful. Stress unleashes a chemical tidal wave of the different hormones and other body responses that have profound effects on all parts of the body. Body Part Eye Mouth and stomach glands Lungs Heart Stomach Intestines Pancreas Response to Stress Pupils widen Reduced production of saliva and digestive fluids Constriction of bronchi Increase of breathing rate Increase of heart rate Long term effects Decrease release of digestive fluids Increase contraction of stomach closer Decrease motility of bowels Reduced release of insulin Increased chance of ulcers Vessels Increase contraction of vessel muscles Skin Decrease perfusion of skin Increase tension of muscles Decrease function of natural killer cells Muscle Immune System Poor digestion of food Asthma-like Increased chance of mismatch between heart muscle perfusion and oxygen need—heart attack Increased chance of bowel cancer Increase chance of prestage diabetes Increased chance of blood pressure Increased chance of stroke Increase chronic pain and arthritis Increased chance of infection