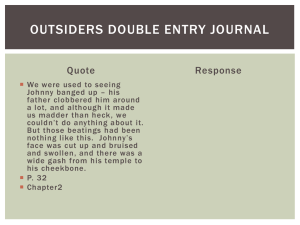

The impact of virtual schools on the educational progress of

advertisement