Submissions for the Proposed Australian Biofouling Management

advertisement

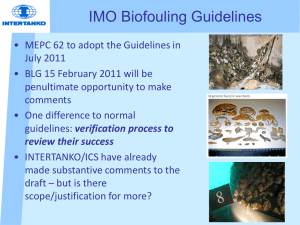

Submissions for the Proposed Australian Biofouling Management Requirements Consultation Regulation Impact Statement A submission received from Aquenal Pty Ltd, Tasmania Submission Q1. Do the proposed operating time restrictions on vessels achieve an appropriate balance between minimising biological risk (which increases with time) and minimising the impact on vessel operators (who may need more time)? If not, why and what would be a better balance? [insert your response here] Q2. How might vessel operators’ behaviour change in response to the proposed regulations? [insert your response here] Q3. What specific types of flow-on costs and benefits to the Australian economy of the proposed regulations might be significant? [insert your response here] Q4. The estimates of costs are based on average vessel numbers from 2002-2009. Is there any activity or trends that suggest any significant change in vessel movement or increased numbers of arrivals? Recommend liaison with [company identifier removed] who have recent experience in this field. Q5. Are the cost assumptions consistent with industry experience? (see appendix D for all cost assumptions). Are there better estimates of costs available? I think the number of days allocated to treatment of large vessels represents a significant underestimate. Cleaning oil rigs, for example, could take up to 30 days. It is highly recommended that DAFF liaise with [company identifier removed] who have direct experience in this area. Q6. Are the other assumptions used to estimate costs and benefits reasonable based on industry experience? If not, how could they be improved? The RIS makes the assumption that hull treatments will be available in the foreseeable future, an assumption which should be viewed with serious caution. For large vessels, the only in water treatment likely to be available by 2013 is in water cleaning, which will be contingent upon the ANZECC guidelines being modified as part of their recent review. While it is recognised that there are potential hull treatments available (e.g. HST, IMProtector), they are far from being proven on large vessels (e.g. bulk carriers, drill rigs) and present enormous technical challenges. One only has to look at similar challenges provided by ballast water treatment – despite more than 20 years of research, there is still no ballast water treatment that is used widely across the industry (apart from ballast water exchange). One would expect a similar timeframe for research into treatment of ships’ biofouling. If no treatment options are available upon implementation of proposed regulations, then in-water cleaning is likely to be the only method available for treating certain vessels. This will present managers with difficult decisions if presented with a vessel that needs treatment, particularly if the vessel is harbouring a SOC. E.g. where should the vessel be cleaned to minimise risk of transefer of SOC? Where can it be cleaned safely? Can it be refused entry? Q7. The methodology for estimating the economic value at risk relies on a series of assumptions about the value of commercial fishing and the Great Barrier Reef. Are there more plausible assumptions or approaches that could be used? There is increasing evidence that many invasive marine pests (IMPs) are most successful in disturbed or polluted environments caused by anthropogenic activities. Undisturbed systems appear to be resistant to invasion by certain IMPs. On this basis, my view is that the risk to the GBR has been significantly over-estimated in the RIS. IMPs are only likely to thrive in nearshore areas adjacent to port developments on the GBR. So long as ecosystem integrity of the broader GBR is maintained by appropriate management, my view is that the vast majority of the GBR is not at risk from invasion by IMPs. It is important to recognise that effective management of IMPs needs to consider overall ecosystem health in addition to direct management focusing on IMPs. In terms of fisheries I think the impacts may have been overestimated. Most fishing operates in coastal environments that have not been subject to anthropogenic modification. The likelihood of impacts to wild fisheries is thus considered low and could be reduced in the model. I consider the main risk IMPs pose to the fishing industry is aquaculture. IMPs have the ability to foul artificial structures associated with aquaculture infrastructure, the industry also often operates in sheltered waters where human impacts are greater and risk of invasion by IMPs is also greater. A suggestion would be to look at the value of the aquaculture industry in Australia as the main source of economic threat, and reduce the threat posed by IMPs to wild fisheries. Q8. What other evidence is there of the potential impacts of non indigenous marine species becoming established in Australia? There is a paucity of robust data demonstrating impacts of IMPs. Many of the examples cited in the RIS describe IMP impacts in areas that have been subject to significant human-mediated modification. While IMPs may still impact such areas, they are not necessarily the primary cause, but often a symptom of poor environmental health. The lack of published evidence of impacts (ecological, environmental) makes it difficult to assess potential impacts of future IMP incursions. It is important to note that despite the large number of IMP introductions that have occurred in Australia, only a small number have become abundant enough to be considered pests. Apart from the economic costs associated with eradication of invasive mussels from Darwin Harbour, it appears that IMPs in Australia have not caused widespread economic impacts. Q9. What is industry’s view of the likely effectiveness of a voluntary approach to reducing the risks associated with biofouling compared to a regulatory approach? [insert your response here] Q10. Do you have any other comments on the Regulation Impact Statement? 1. Validation/verification of inspections A major concern is the fact that no validation of vessel inspections/treatment by government is being proposed in the RIS. Without such validation, there is a strong chance that the quality of inspection/treatment processes may be compromised. For the process to be robust, two elements are considered necessary, including (1) A minimum standard (inspection/treatment), along with (2) verification/validation which would ensure that these processes are being conducted in a rigorous manner. 2. Species List While there is always debate surrounding the make-up of species lists, I have several concerns. The number of species is very high, particularly given that inspections will be based on visual assessments. There are also several species that would be difficult to survey from a practical point of view in a biofouling inspection. Suggestions for adjusting the list are provided below: Freshwater species were included in the species risk assessment, taking the precautionary approach. My view is that such species present negligible translocation risk and could be excluded, as follows: - Crangonyx floridanus - Dikerogammarus villosus - Gammarus tigrinus - Gmelinoides fasciatus - Corbicula fluminea - Dreissena bugensis - Dreissena polymorpha Microscopic species should be excluded from the list, since they cannot be practically surveyed during visual inspections. Species under this category include: - Acartia tonsa - Corethron criophilum - Pseudochattonella farcimen - Chattonella antiqua - Bonamia ostreae The merits of including small mobile species is also questionable, since such species would be difficult to detect during a visual biofouling inspection. Furthermore, the taxonomic identification of such species would almost certainly require specialist expertise, since these animals are notoriously difficult to identify to species level. Species in question include: - Ampelisca abdita - Gammarus tigrinus Inclusion of Didemnum vexillum on the list is problematic from a taxonomic perspective. This species can only be reliably identified using genetic techniques. Unless a provider of molecular services can guarantee a prompt turnaround (considered unlikely), then there will be problems with implementing the model proposed in the RIS. Inclusion of parasites (e.g. Bonamia ostreae Briarosaccus callosus, Loxothylacus panopaei, Sylon hippolytes, Anguillicola crassus) on the list is problematic from an inspection perspective. It may be more sensible to target potential hosts, but this brings further complexity to the inspection process. Inclusion of Codium fragile ssp. atlanticum on the list is problematic. In a recent assessment it was suggested that one variable species of C. fragile should be recognised (Guiry 2008). On this basis, inclusion of a Codium fragile subspecies on the list would not be warranted, since introduced Codium fragile subspecies are established in Australia. I understand that the risk assessment framework included a prescriptive set of guidelines for determining human health impacts. However, I find it hard to accept the ‘high’public health ranking of filter feeding species, justified only by the fact they could accumulate toxins. It is hard to see where introduction of these species would result in additional risk to public health (given that they would be consuming native shellfish species that also accumulate toxins). The key threat to public health comes from the toxic algae, not the species of concern. On this basis I think that the overall risk has been overestimated for species including Mya arenaria and Crassostrea ariakensis: 3. Species based approach to biofouling management The current federal government approach to biofouling management is species based, rather than based on level of biofouling. While there are pros and cons with the respective approaches (i.e. species based or level of biofouling), consideration should be given to a combined approach, where level of biofouling is also taken into account. Vessels with very high levels of biofouling may still represent a significant biosecurity risk even under circumstances where no SOC are detected in a biofouling inspection. Heavily fouled vessels are more likely to harbour potential invasive species that were not revealed in the risk assessment. Furthermore, there remains the possibility that species not previously shown to be invasive in other parts of the world could exhibit invasive characteristics when established in Australia for the first time. Thus, a suggested criteria in a combined approach would be ‘SOC detected OR high risk level of biofouling present’. Under this approach there would be a need for objective criteria for ‘high risk biofouling levels’. If such an approach was employed, it would be necessary to consult with experienced workers in this field to reach an agreement on what should be considered a ‘high risk’ level. For example, a high cover (>50%) of tertiary level fouling might be considered a ‘high risk’ biofouling level. The other important advantage of this approach is that it would also reduce the likelihood of translocation of small mobile species (e.g. amphipods) that may be difficult to detect and/or identify during a biofouling inspection. Such mobile animals are much more likely to be associated with high levels of fouling compared to cleaner vessels.