Laryngology seminar

advertisement

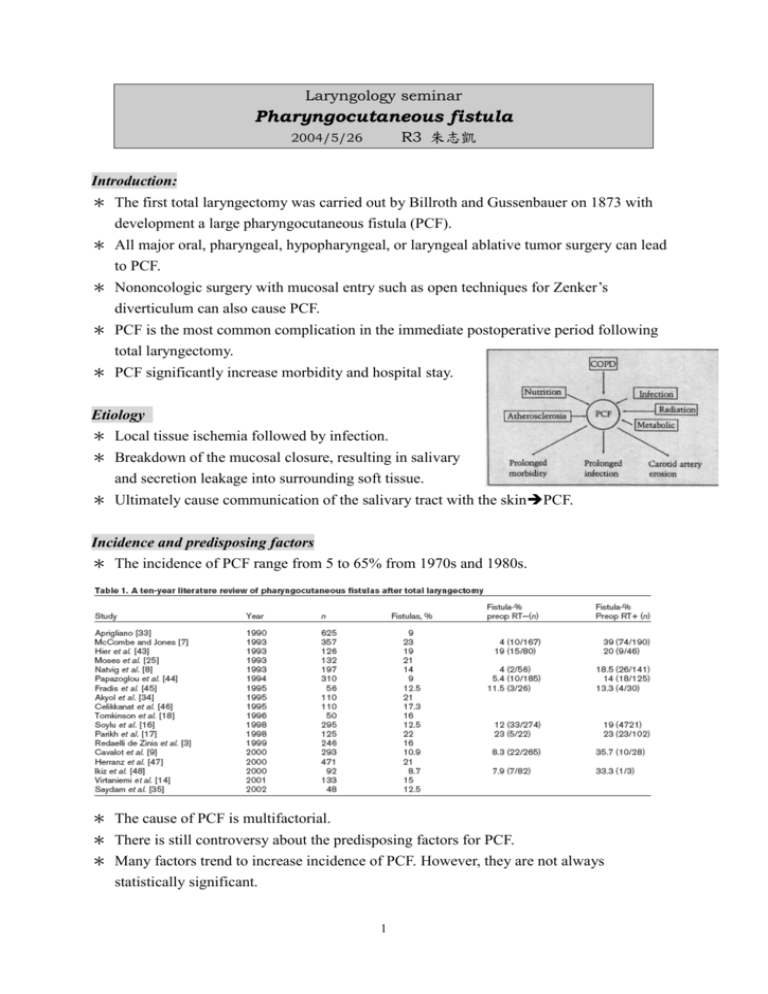

Laryngology seminar Pharyngocutaneous fistula R3 朱志凱 2004/5/26 Introduction: * The first total laryngectomy was carried out by Billroth and Gussenbauer on 1873 with development a large pharyngocutaneous fistula (PCF). * All major oral, pharyngeal, hypopharyngeal, or laryngeal ablative tumor surgery can lead to PCF. * Nononcologic surgery with mucosal entry such as open techniques for Zenker’s diverticulum can also cause PCF. * PCF is the most common complication in the immediate postoperative period following total laryngectomy. * PCF significantly increase morbidity and hospital stay. Etiology * Local tissue ischemia followed by infection. * Breakdown of the mucosal closure, resulting in salivary and secretion leakage into surrounding soft tissue. * Ultimately cause communication of the salivary tract with the skinPCF. Incidence and predisposing factors * The incidence of PCF range from 5 to 65% from 1970s and 1980s. * The cause of PCF is multifactorial. * There is still controversy about the predisposing factors for PCF. * Many factors trend to increase incidence of PCF. However, they are not always statistically significant. 1 * The local factors seem to play a major role. * Nutrition 1. Malnutrition is reported to be present in 35 to 50% of all head and neck caner patients. 2. BW loss more than 10% within 6 months is at a greater risk for major surgical complications. 3. A postoperative Hb lower than 12.5 g/dL has been reported to increase the risk of PCF. * Preoperative radiation 1. All studies within the last decade showed PCF rates were higher in pre-op R/T group. 2. The difference was not always significant. 3. Risk factor: a. Radiation dosage, field size and fractionation protocols. b. Hyperfractionation vs. split-course c. Co-60 vs. accelerated radiation (photons). d. Significantly increase risk in cobalt/roentgen than photons photons have advantage of sparing the subcutaneous tissue. e. The interval from the end of RT to operation. f. CCRT: 77% vs. 20% complication rate in the patient received surgery within 1 year and more than 1 year of CCRT. 2 4. The PCF in peroperative RT patients: a. Appeared earlier and closed later. b. The fistulas were significant larger than non-RT group. c. Longer healing duration. d. More frequent progression to advanced muscle necrosis, soft tissue necrosis, vascular exposure, and fistula expansion. e. Often need surgical intervention earlier than nonirradiated patients. * The extent of surgical defect (pharyngolaryngectomy), comorbidity (CHF), and nonglottic tumor site carried an increased risk. * Histological infiltration of tumor’s surgical margins: 11% vs. 38% (Konstantinos). * No association between PCF and age, gender, patient comorbidity condition (DM), TNM stage, choice of ablation, reconstruction, modality of post-op feeding, or TE puncture (Parikh). Signs and symptoms * The PCF will usually appear 7 to 11 days after surgery. * First clinical sign: wound erythema with neck and facial edema/swelling. * Fever (38.5oC) during the first 48 post-operative hours (Friedman). * Tenderness of the skin incisioin. * Further PCF progression: surgical wound contamination by oropharyngeal content with wound dehiscence and flap necrosis. * Esophagogram: sinus tract > 2 cm (recommend in patients with significant risk factors). * Wound amylase levels: elevated amylase levels on the post-op days 3, 4 and 5 can be a significant predicator of PCF (Aydgan). Prevention * Perioperative nutritional aupplementation 1. Pre-op enteral or parenteral alimentation. 2. Restore serum protein levels. 3. Blood transfusion if needed. * Perioperative antibiotics 1. Prophylatic ABx: administered within 30 min before surgery. 2. Coverage of aerobic with penicillin or cephosporin and anaerobic with metronidazole. * Improve surgical technique 3 1. Closure type: T or Y vs linear. 2. Watertight two-layer to three-layer of mucosal closure. 3. Catgut showed a higher rate of PCF than Vicryl. 4. Nonclosure of the pharyngeal constrictor muscle (Wang): reduce the pharyngoesophageal pressure lower PCF rate. 5. Cricopharyngeal myotomy during total laryngectomy for lower intrluminal pressure. * Reconstruction with flaps 1. Patient with significant radiation effect or extensive mucosal defect may be considered for flap reconstruction rather than primary closure. 2. Routine addition of pectoralis major myogenous flap (PMMF) at pharyngeal closure between the pharyngeal anatomic line and skin will dramatically reduced PCF: 22.9% vs. 0.6% (Thomas). * Gastroesophageal reflux prophylaxis: 1. Ranitidine and metoclopramide hydrochloride parentally for 7 days. 2. 21 patients with no PCF compared with 26% of PCF in control group (Seikaly). * Early oral feeding: 1. Traditional standards for initiation of oral feeding: 7 days for nonirradiated patient and delayed for irradiated patient. 2. Early oral feeding without NG insertion (even started as early as 24 hours after surgery) dose not increase the incidence of PCF. 3. Early oral feeding can shorten the hospital stay. 4. The NG tube has also been demonstrated as an ascending pathway for intestinal flora and to cause local trauma on the fresh suture with local tissue damage. Mamagement of PCF * Classification of PCF: 1. Small fistula, less than 0.5 cm in diameter. 2. Medium fistula, 0.5 to 2.0 cm in diameter. 3. Large fistula, more than 2.0 cm in diameter. * Small or medium size fistulas usually close spontaneously with conservative treatment. Conservative treatment 1. Residual tumor should be excluded first. 2. Principles: a. Salivary diversion. b. Complete debriment. c. Nutritional support. d. Antibiotics. 3. Early drainage of fluid with debriment of necrotic 4 tissue 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. a. Small fluid collection: repeat aspiration b. Large with abscess: open drain (if necessary, open the previous suture line) Pressure dressing for flap down. Silicone salivary bypass tube. Placement of a cuffed tracheostomy tube to prevent aspiration. Tube feeding with adequate nutrition. Successful rate: 50% to 80% Surgical repair * Surgical intervention is reserved after failed by conservative treatment. * Timing: 1. Do not operate before 40th postopeartive day. 2. Control infection 3. Improvement of local flaps * Method of surgical repair (depending on size of PCF and local condition). 1. Primary closure. a. Rarely possible. b. Small fistula with minimal sounding tissue loss. c. Fibrin glue-reinforced closure. 2. Flap reconstruction: Adjacent flaps, distant pedicle flaps, free flaps, and combination of the above. * Flap reconstruction. 1. Flap reconstruction should not be undertaken until secondary healing healthy granulation tissue has occurred. 2. Classification: type I~IV; type IV is most common. 3. Adjacent flaps: a. SCM (type III and IV) and trapzius flaps within the RT field prone to failure. b. Deltopectoral flap: multiple stage. 3. Distant pedicle flaps: a. PMMCF: effective for all types of fistula. b. Latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flaps: extensive resection and additional bulk and skin were needed. 4. Free flaps: Radial forearm and jejunal flaps (circumferential pharyngoesophageal defect). 5. Radial forearm flap in combination with PMMF. 6. Double paddle myocutaneous flap. 7. Due to the reliability and highly successful rate for all types of 5 fistulaPMMF/PMMCF remains the workhorse flap for PCF reconstruction. Conclusion * The cause of PCF is multifactorial and no definite predisposing factor. * Preopeartive radiotherapy. * The most PCF can be treated successfully by conservative treatment. * Surgical repair should be held until the conservative treatment failed. Reference: 1. Makitie AA, Irish J, Gullane PJ, Pharyngocutaneous fistula. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003, 11:78–84. 2. Johansen LV, Overgaard J, Elbrond O: Pharyngo-cutaneous fistulae after laryngectomy: influence of previous radiotherapy and prophylactic metronidazole. Cancer 1988, 61:673–678. 3. Redaelli de Zinis LO, Ferrari L, Tomenzoli D, et al.: Postlaryngectomy pharyngocutaneous fistula: incidence, predisposing factors, and therapy. Head Neck 1999, 21:131–138. 4. Cavalot AL, Gervasio CF, Nazionale G, et al.: Pharyngocutaneous fistula as a complication of total laryngectomy: review of the literature and analysis of case records. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000, 123:587–592. 5. Teknos TN, Myers LL, Bradford CR, et al.: Free tissue reconstruction of the hypopharynx after organ preservation therapy: analysis of wound complications.Laryngoscope 2001, 111:1192–1196. 6. Virtaniemi JA, Kumpulainen EJ, Hirvikoski PP, et al.: The incidence and etiology of postlaryngectomy pharyngocutaneous fistulae. Head Neck 2001,23:29–33. 7. Soylu L, Kiroglu M, Aydogan B, et al.: Pharyngocutaneous fistula following laryngectomy. Head Neck 1998, 20:22–25. 8. Parikh SR, Irish JC, Curran AJ, et al.: Pharyngocutaneous fistulae in laryngectomy patients: the Toronto Hospital experience. J Otolaryngol 1998, 27:136–140. 9. Tomkinson A, Shone GR, Dingle A, et al.: Pharyngocutaneous fistula following total laryngectomy 6 and post-operative vomiting. Clin Otolaryngol 1996,21:369–370. 10. Singh B, Cordeiro PG, Santamaria E, et al.: Factors associated with complications in microvascular reconstruction of head and neck defects. Plast ReconstrSurg 1999, 103:403–411. 11. Friedman M, Venkatesan TK, Yakovlev A, et al.: Early detection and treatment of postoperative pharyngocutaneous fistula. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999, 121:378–380. 12. Krouse JH, Metson R: Barium swallow is a predictor of salivary fistula following laryngectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992, 106:254–257. 13. Seikaly H, Park P: Gastroesophageal reflux prophylaxis decreases the incidence of pharyngocutaneous fistula after total laryngectomy. Laryngoscope 1995, 105:1220–1222. 14. Medina JE, Khafif A: Early oral feeding following total laryngectomy. Laryngoscope 2001, 111:368–372. 15. Saydam L, Kalcioglu T, Kizilay A: Early oral feeding following total laryngectomy.Am J Otolaryngol 2002, 23:277–281. 16. Wang CP, Tseng TC, Lee RC, et al.: The techniques of nonmuscular closure of hypopharyngeal defect following total laryngectomy: the assessment of complication and pharyngoesophageal segment. J Laryngol Otol 1997,111:1060–1063. 17. Peat BG, Boyd JB, Gullane PJ: Massive pharyngocutaneous fistulae: salvage with two-layer flap closure. Ann Plast Surg 1992, 29:153–156. 18. Ikiz AÖ, Uca M, Güneri EA, et al.: Pharyngocutaneous fistula and total laryngectomy: possible predisposing factors, with emphasis on pharyngeal myotomy.J Laryngol Otol 2000, 114:768–771. 7