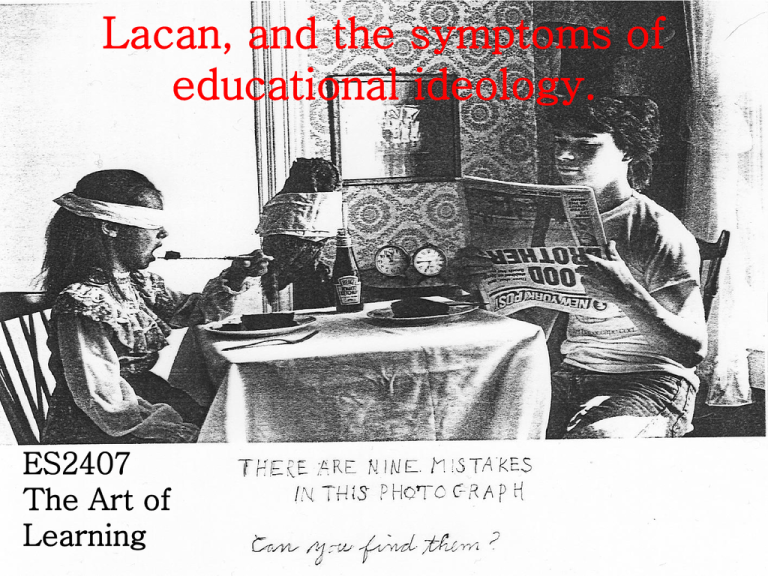

Lacan, and the symptoms of

educational ideology.

ES2407

The Art of

Learning

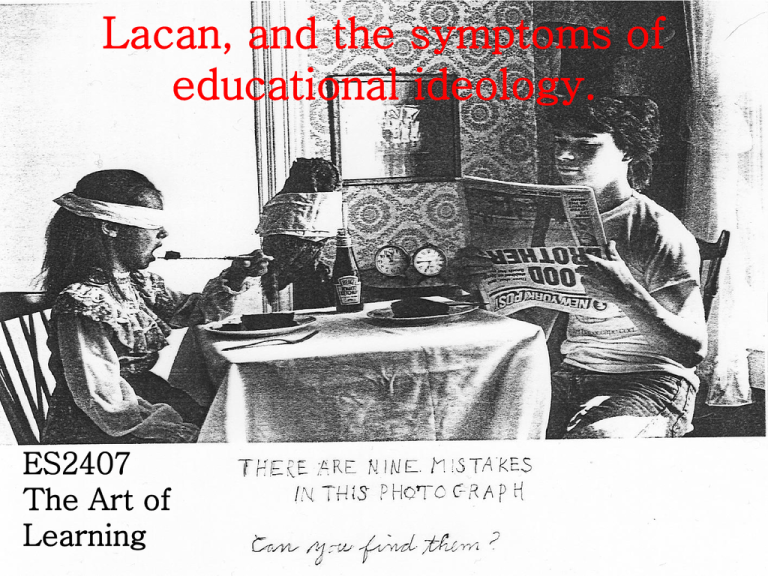

The introductory text to the illustrations

of lacanian fantasy discussed the idea of

thinking about society as though it were a

person, generating images and figures as

social fantasies - symptoms of ‘its’ mass

ideological formations. The task now is to

search for symptoms that might

reasonably be associated with education.

We will do this by thinking about ideology

in general, and then employ a number of

classical myths to tease out those

ideologies that seem central to education.

The last chapter in Zizek’s The Plague of

Fantasies is entitled, ‘Cyberspace, or, the

unbearable closure of being’. In the first section

he discusses the notion of symptom in relation to

social ideologies.

His starting point is the absolute nature of

ideology itself. Once it is implemented, its

particular principle of formation runs through

every instance of content – think of ideology as

being like a frame. So, within it, the issue of

whether or not a particular content is present or

not is contingent – and of no significance to the

maintenance of the ideological domain itself, or a

threat to its universal truth.

But to quote Zizek,

‘A symptom, however, is an element which

– although the non-realisation of the

universal principle in it appears to hinge

on contingent circumstances – has to

remain an exception, that is, the point of

suspension of the universal principle: if

the universal principle were to apply to

this point, the universal system itself

would disintegrate.’

Think of feminism’s advance. In every instance the

assumptions of an exclusive masculinity – in respect of

deity, kingship, wisdom, intellectual prowess, and even

the warrior virtues – have had to eventually

accommodate the presence of women as symptom.

Such symptoms appear as either ‘tokens’ satisfying

some higher, extra-ideological principle, or else appear

in disguise – as compromised forms of femininity which

avoid overt conflict with the universal principle. As

Zizek indicates, the alternative – full acceptance of their

status as women – leads to the collapse of the prior

ideological system, i.e., the combination of universal

principle and contingent content – now seen to be not so

contingent as all that. In effect, then, the symptom is a

necessity generated by the ideological structure itself.

To further illustrate this example we

need some sexualised ‘symptoms’ to

think with, and since this is such a central

aspect of contemporary society, it’s

reasonable to ask if our education system

responds in a particular way. In fact does

it even recognise the difficulties faced by

those who are expected to act as

‘tokens’, or those who are condemned to

fulfil patriarchal assumptions of

femininity? And if it doesn’t, what does

this tell you about its ideology?

I. Athena - goddess of wisdom,

justice, civilisation, strategic

warfare, the female arts, and the

virgin patron of Athens. She is

the daughter of Metis, a Titan,

whom Zeus swallowed after

coupling with her so as to avoid

a prophesy that their progeny

would be greater than himself.

But Metis was already pregnant

and gave birth to Athena inside

Zeus. Later, suffering from a

terrible headache, Zeus asked

Hephaestus to split open his

forehead, from which Athena

burst forth fully armed with

weapons given to her by her

mother.

II. Pandora - first woman and

the origin of evil. Her name

means ‘all-gifted’, since each

god gave her a unique gift to

add to her seductive charms.

Zeus had ordered Hephaestus

to mould her out of earth as a

‘beautiful evil’ – to balance the

benefits of fire given to men by

Prometheus. Epimetheus, his

brother, accepted her as a wife

– despite Prometheus’ warning.

For her dowry she brought a

jar holding all the evils of the

world, and once on Earth she

opened it, releasing them, until

only hope remained inside.

Clearly, Athena is no token! But, nevertheless, her

femininity is disguised so as to match a still dominant

patriarchy. She has an almost masculine face, and any

obviously feminine or maternal physical qualities are

hidden by her clothing and military equipment. Not only

does she carry a spear and shield, she also wears a

helmet and chest armour that presents the head of a

gorgon. She has no lovers, is a virgin, and even as an

adoptive mother her ‘son’ is always represented as a

serpent. Finally, and perhaps of most significance, her

birth ‘mother’ is Zeus, the father of the gods. The

principal fantasy at play here seems to be what Zizek calls

the ‘impossible gaze’ – the narrative creation of a selfwitnessed moment of ‘birth’ to account for the

reconfiguration of the symbolic order that she herself

bring about – to some degree. She is emblematic of a

state of transition.

Given the history of the Twentieth Century, it is

remarkable that even towards the end of that

century our education system offered no

information about an experience that half the

school population were likely to face at some time

during their working lives. Today, the problem

has not gone away; and arguably, it is even more

of a requirement than before. The remaining

‘bastions’ of masculine exclusiveness are deeply

entrenched, while many areas of apparent sexual

equality still resist the breaking of their own

‘glass ceilings’. Men also are beginning to

experience equivalent transitions as they enter

work places previously assumed to be exclusively

‘feminine’, such as nursing and infant education.

If education’s silence about transitional experience is

surprising, its silence with respect to the implications of

the Pandora figure is deafening: she figures in the

education of every pupil, be they male or female, beautiful

or plain, accepting or rejecting their implied social role.

As the seductive bringer of evil she is neither token nor

transitional form. Her first ‘veil’ of fantasy is the

transcendental schematism of desire – teaching men how

to desire and women how to be desirous. Her second veil

is the inter-subjective. Here, she introduces the

mysteries, risks, and specific co-ordinations within the

symbolic order intrinsic to gendered inter-subjectivity.

Her own entry into this order is as the carrier of the Real

– the troubles and confusions which irrupt through the

ordered surfaces of the world. And, finally, hope itself is

her agalma, that within her which is greater than herself.

Athena and Pandora offer simplified

ideological figures/models which can be

used to tease out the ideologies and

symptoms associated with education

under patriarchy. As we have just seen,

we drew two blanks which were highly

significant because of their relevance to

society and experience in general, and

yet the official education system ignores

them – what is this telling us about the

nature of this education?

The next set of figures provides us

with insight into the ideologies of

teaching itself. Note that here we

recapitulate many of the risks

associated with the psychoanalytic

‘transference’.

The most obvious aspect of this is the

assumption that the ‘good’ teacher

will make enlightened interventions –

and so, to the Master’s workshop!

III. Pygmalion was a

sculptor who lived on an

island where the women

had rejected the deity of

Aphrodite. In response,

she made all the women

permanently promiscuous –

and Pygmalion began to

live alone. He dreamt of a

perfect woman, and to

relieve his loneliness he

made a statue of his

fantasy. He loved it - and

dressed it in precious

clothes and jewels. Taking

pity on him, Aphrodite gave

life to his statue.

The ideology for which Pygmalion may figure as

model is not simply one keen to police any

impropriety between teacher and pupil – refer to

Socrates in his Symposium. It features instead

the risk of any pupil-teacher relationship - one in

which the teacher is given licence to transgress

the respect for separate identities normally

accorded to private individuals. (The phrase, ‘in

loco parentis’, is often used as an epithet for

much that is unusual about public schooling.)

Pygmalion’s ideal statue implies that although this

process will result in a new ‘life’ for the pupil, it

will be one determined by the teacher according

to his/her desire. Cf. Michaelangelo: I find and

release forms hidden in the stone.

In lacanian terms, rather than the teacher acting as a

specialised token for symbolic authority, s/he has allowed

herself to regress to the realm of the Imaginary subverting her pupil’s entry into the symbolic – offering

herself as the authority – the Other – one ruthlessly

searching for its own image reflected in the responses of

its ideal students. This is in opposition to working

‘through’ the pupil’s transference so as to eventually

release their individuality. (See, for example, The Prime

of Miss Jean Brody, but also The Dead Poets Society.)

Recall also that narratives impose temporal distance

between contradictions existing within the same context,

imposing a before and after, allocating victory to one side

and defeat to the other. The myth of Pygmalion tells of

how godliness might be rewarded, but Mary Shelley’s

Frankenstein offers an ironic riposte.

IV. Ariadne, daughter of King Minos

of Crete, has a half-brother – the

Minotaur: half man, half beast –

trapped in Daedalus’ labyrinth. Her

other brother is killed in Athens Minos attacks, defeats the city, and

demands that it sends seven youths

and seven maidens every nine years

to Crete as sacrifice to his other son.

Theseus, future ‘father’ of the new

Athens, joins the victims. Ariadne

falls in love on first sight and plots

his escape. Before the sacrifice, she

leads him to the labyrinth, giving him

a sword and spindle of thread. Using

these, Theseus kills the monster and

escapes from Crete with Ariadne, but

later abandons her on Naxos.

Clearly, we witness another moment of birth – and a

different model of the ‘good’ teacher. In this,

Ariadne appears at first sight to act as both selfsacrificing guardian and guide to her pupil-hero,

Theseus, who will follow her lead through love, but

then discard her.

But we know that narratives typically transcribe

co-present contraries into a before-and-after

structure, so the direct reading of this myth is that

the triumph of Theseus over the Minotaur conceals

two opposing ideas. Both the monster (Ariadne’s

half-brother) and the future-hero are products of

the co-mingling of gods and mortals - even sharing

the same godly ‘father’: Poseidon.

So it is more accurate to think of the Minotaur

as a shadow image or negation of Theseus – its

singular bestiality matching his heroism.

Consider, then, Ariadne’s spindle of red thread;

the gender associations are clear (and didn’t

Socrates describe himself as a ‘midwife’?),

Equally, knots and thread have always been

associated with problems and their solution.

The labyrinth is both complex knot and problem:

Theseus must solve them both; but this will

involve self-mutilation – his ‘shadow’ must die

so that a new self-image can shine more

brightly. On this reading, progress will involve

no more than the denial of ‘base’ impulses, etc.

The lacanian conclusion is more daunting

than this suggests. The price of progress is

not simply the denial of some part of the

self. With each step upward and forward,

the pupil-hero’s shadow shifts – and as it

does so both the labyrinth and the Minotaur

also change their nature. Ariadne (the

teacher) is less a guide than a guardian, and

less a guardian than a messenger of

constant difference: ‘Here heroism will find

no final resting place – other than your final

fall.’

The next two models help to make explicit

further complexities in the pupil-teacher

relationship. Both Phaedra and Medea have

served as the central protagonists in many

plays, novels, musical works, and in the

case of Phaedra, a film. There are,

therefore, for the first time, versions that

can be chosen to match one’s analytic focus.

Each figure presents a married woman with

children who is provoked to question the

stability of her marriage. In each case, the

response is extreme.

V. Phaedra is another daughter of Minos and Pasiphae. She

marries Theseus and has two sons by him, and also

becomes mother to Hippolytus, Theseus’ son by a previous

marriage.

The simplest version of

the myth has Phaedra

falling in love with her

step-son, who spurns her.

In revenge, she tells

Theseus that Hippolytus

raped her. Theseus

responds by calling on his

father, Poseidon, to kill the

youth.

The god sends a huge bull from out of the sea which

stampedes Hippolytus’ horses as he passes in his chariot.

He is pulled into the reins and dragged to his death. On

hearing of this, Phaedra kills herself in guilt and remorse.

VI. Medea uses magic to

help Jason win the Golden

Fleece, and helps him to

escape with her by killing

one of her own brothers.

She becomes Jason’s wife,

and bears him two sons.

Later, he discards her so he

can marry a younger and

more respected princess.

Medea responds by killing

the princess, the girl’s

father, and then her two

sons before fleeing to

Athens.

As with Pygmalion, there are explicit sexual relationships in

both myths that can limit the scope of application, but if these

are put to one side, one has a powerful analytic model to

think with. In the case of Phaedra, the obvious response is to

take the educational interpretation as a warning against

excessive emotional attachment on the part of a teacher for

any of the children in their charge. More developed versions

of the myth move matters further on. Hippolytus is said to

spurn Aphrodite, goddess of erotic love and sexual beauty,

preferring to remain a virgin devoted to Apollo’s twin sister,

Artemis, goddess of the hunt and of nature, a virgin herself

but also goddess of birth and nurture. It is therefore

Aphrodite who fills Phaedra with lust for Hippolytus, in

revenge for her rejection; and Phaedra spends the rest of

what remains of her life trying to fight against this enforced

desire. What is striking in this revised figuration is that both

the ‘teacher’ and the ‘pupil’ suffer because they reject the

entry of love – however understood - into their relationship.

Our interest in a wider sense of education may therefor

suggest an analysis in which both ‘teacher’ and ‘pupil’ are

seen to be at fault in refusing the changes to themselves

that will be brought about through mutual affection. The

idea of a more experienced woman entering into a positive

sexual relationship with a less experienced younger man is

still in the process of becoming acceptable in literature and

film, e.g. The Graduate . But there are many examples

where relative equality, often despite the patriarchal norm

of rejection, becomes the eventual basis for mutual growth,

e.g. Pride and Prejudice, North and South, and even Women

in Love. But the myth of Phaedra is, in fact, set in motion

by the pupil’s initial offence: Hippolytus rejects the power

of love, and the myth continues to circle around this fact.

Transcribing this, the pupil rejects desire – his/her lack –

as a source of radical change to self. Both Freud and

Lacan think all desire is, ultimately, a desire to be loved, so

analysis starts here – leading, perhaps, to Narcissus.

There are a number of variations to the myth of Medea.

The story of filicide seems to have been Euripedes’ own

invention, but it has become a constant feature since

then. The general assessment of the relationship

between Jason and Medea is as follows: this is a story

that starts with treachery and murder, and ends with

suspicion, jealousy, and merciless revenge. You should

know by now, however, to start your own analysis by

placing the more striking aspects of a myth in brackets –

releasing them selectively as your transcription proceeds.

N.B. some versions have focussed on how Medea has

little choice but to kill her sons since their fate – if Jason

denies their inheritance – will be exile, death, or slavery.

Various transcriptions suggest themselves based on this,

but start by making Jason the teacher, Medea the pupil,

and her children Jason’s ‘teachings’. Now reverse this to

get the feminist reading, and try ‘teachings’ = poison!

The last illustrative models feature the idea

of educational trajectories. Plato’s The

Death of Socrates illustrates the rise and

apparent ending of a quest for wisdom,

while Oedipus is used by both Freud and

Lacan to model the transition of the child

from family to society. We consider here a

question raised in the notes on Freud for

Education, Social, and Political Thought:

does the myth of Oedipus adequately

express feminine experience of this

transition?

VII. Oedipus. King Laius and

Queen Jocasta of Thebes are

warned that if their child is

allowed to become an adult it will

murder his father and marry his

mother. The king orders the

child’s feet to be pinned together

and the infant abandoned. It is

rescued by a shepherd, and later

adopted as the son of another King

and Queen. As a youth, Oedipus is

warned he will kill his father and

marry his mother, so he flees his

home. On his travels he meets an

elderly stranger, they quarrel, and

Oedipus kills him. Oedipus reaches

Thebes – besieged by a monster,

the Sphinx.

The monster eats anyone who cannot answer its riddle:

which animal has 4 feet in the morning, 2 at midday, and 3

in the evening? Oedipus replies that it is Man, the Sphinx

screams in fury, and vanishes back into an abyss.

Oedipus becomes the hero of

Thebes, and he marries the

recently widowed Queen, (his

own mother) Jocasta. They

reign in peace for some ten

years and have a number of

children together – then

plagues break out in the city.

The famous prophet, Tiresius, is called. He declares that

the plague will only end when the murderer of King Laius,

Jocasta’s previous husband and Oedipus’ father is

found. Oedipus turns ruthless detective and soon the old

shepherd who had originally rescued him is discovered.

The shepherd’s testimony,

and other evidence, point

conclusively towards Oedipus

himself as the

murderer. Jocasta, both his

queen and mother, runs into

the palace and hangs herself

in their bedroom. Oedipus

blinds himself with her clasp

as he accepts his own guilt.

He begs that he be banished

from Thebes, but one

daughter from his incestuous

marriage volunteers to

accompany him as a guide;

she is called Antigone.

Analysis of the Oedipus myth as a model of an

educational trajectory will take place in the lecture. As

you now know, as far as feminine experience of individual

agency is concerned, the shift from family to society is

theorised as being dominated by the recognition of lack.

For Freud it is the literal lack of a penis that drive’s the

young girl to eventually become reconciled to her

physical castrated state: for Lacan, castration is shifted

to the Symbolic Register, but he also thinks that a

woman’s ability to exercise agency within this realm is

always dependent on being able to co-opt forms of

masculine agency.

One of Freud’s followers, C. G. Jung, suggested that the

myth of Electra could provide a more suitable model for

feminine experience. We therefore end this PowerPoint

with a summary of the Electra myth that will be used in

discussion.

VIII. Electra plots with Orestes, her brother, to kill her

mother, Clytemnestra and Aegithus, her step-father, for

murdering her actual father, Agamemnon.

This murder is itself

prompted by the fact that

Agamemnon sacrificed

his oldest daughter,

Iphigenia, in order to get

Artemis to allow him and

his fleet to leave Athens

and sail to Troy, thus

beginning the Trojan

war.

Electra and Orestes succeed in their plan, but then have

to atone for their shameful act by purifying their souls.

(By far the strongest version is developed by Sophocles.)

A Reminder

The following sequence of developmental experiences seems to be well

established: primary bonding with the mother or principal care-giver,

corresponding to sensation being organised around the mouth. Subsequently this

moves to control of the faeces and the anus, and at about the age of 4 – 5

attention shifts to exploring the genitals and the pre-sexual pleasure they can

generate; the child also becomes intensely curious about any observed differences

in genital anatomy between individuals during this ‘phallic’ stage. Rather than at

adolescence, then, psychoanalysts locate the Oedipus Complex at this early time

within the individual’s life. Essentially, the ‘complex’ amounts to that experiential

process by which the individual comes to associate themselves with the same-sex

individual within the family setting, and at the same time relinquishing any

thoughts of competing against this same half of the partnership for the love of the

opposite partner, accepting, therefore ex-familial heterosexual social

relationships, and initiating the formation of a super-ego modelled on the ‘lawgiving’ capacity of the same-sex partner.

Both sexes start by loving the mother. In the case of boys, what then drives this

process is the fear of castration by the father. Girls come to recognise they lack a

penis (‘penis envy’) and therefore cannot compete against the father for their

mother’s attention. Initially, they blame their mothers for this assumed

imperfection, but later become reconciled with their mothers through the

formation of a superego, i.e., they come to accept their ‘castrated’ state and redirect their affection towards the father or father-substitute.

D.M.B. 2011.