Goldstein v. McNeil

advertisement

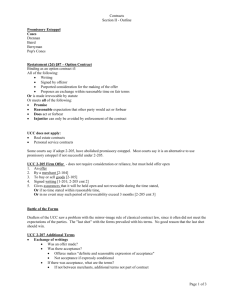

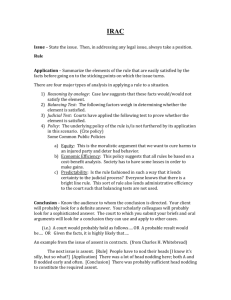

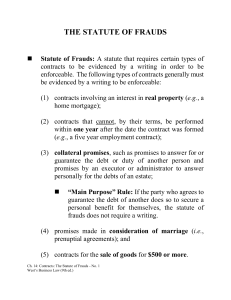

Anglo-American Contract and Torts Prof. Mark P. Gergen Class Ten Objective theory Offer and acceptance Statute of Frauds “A promise that the law will enforce” Contract is thought of as “private legislation.” A forward-looking commitment to another that can be enforced in court. Concept of contract excludes gift, misstatement, etc. . . Doctrine of consideration generally defines what promises are legally enforceable. Presence of consideration can be understood as a surrogate for requirement of an intent to be legally bound. In US reliance/promissory estoppel is an alternative basis for enforcing a promise. In England promissory estoppel can be used negatively or defensively but not positively or affirmatively. Obligation in contract requires 1) 2) 3) An apparent expression of intent to undertake an obligation (e.g., by promise, agreement, offer & acceptance . . .) A legal basis for enforcing the obligation such as consideration. Sometimes written evidence of the obligation under the statute of frauds. Objective theory When there is a misunderstanding about the existence or meaning of a contract, the law adopts the more reasonable view. For example, generally a party is held to the terms of a contract he signs even if does not read the contract. If you order something at a restaurant without looking at the price, then you are obligated to pay the menu price even though you would not have ordered what you did had you known the price. See Adams v. Lindsell, p. 131. D mails an undated offer that is mis-addressed and so delivered late. P mails immediate acceptance. D sells goods in interim. There is a contract. D was more at fault in the misunderstanding about the timeliness of the acceptance. Contract does not require a “meeting of the minds.” A person may conclude a contracting not intending to do so. Common law rejects the “will theory” of contract. A contract is a product of outward manifestation of intent. Not actual intent. But assent is not always determined objectively. Generally the law gives effect to shared subjective understanding. A and B pretend to make a contract to fool C. There is no contract between A and B. A known and sometimes even a suspected error in communication cannot be exploited. A gives B papers to sign knowing B will not read them carefully. A craftily includes among the papers a contract A knows B would never agree to. There is no contract though B signs. A may be liable for fraud for knowingly misleading B. Raffles v. Wichelhaus, p. 133. Contract for India cotton to be delivered by the “Peerless.” B understands this to mean the Peerless that sailed from India in October. S understands it to mean the Peerless that sailed in December. B refuses to accept delivery of cotton from the later vessel. Milward makes 2 argument at p. 134: i) the misunderstanding was immaterial; ii) evidence there were 2 ships is inadmissible to challenge written agreement. Mellish argues there was “consensus ad idem” (“no meeting of the minds”) and so no contract. Court agrees. Unstated premise is that neither party was more at fault. If point of disagreement is material and performance has not been received and accepted, then there is no contract. The contract fails based on “mutual misunderstanding.” Contract is voidable, not void. Either party may opt to affirm the contract by embracing the other party’s understanding. The misunderstanding must be material. Review Objective theory--if there is a misunderstanding about existence or terms of contract, then courts generally adopt the more reasonable view. Courts will give effect to shared subjective understanding. A party may not take advantage of an error in communication if he knows or has good reason to know of the error. Mutual misunderstanding on a material term makes a contract voidable. “An offer is the manifestation of a willingness to enter into a bargain, so made as to justify another person in understanding that his assent to that bargain is invited and will conclude it.” Restatement 2nd § 24 Did the sender reasonably appear to intend to invite the recipient to conclude a contract by acceptance? An offer terminates if a stated time limit passes, after a reasonable time, if it is rejected, if it is revoked, if the offeror dies, etc . . . . pp. 125-129. An acceptance must be unequivocal and on the terms of the offer to be effective. pp. 129-130. “Mirror image rule.” This is relaxed by UCC 2-207. Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Co., p. 124 Advertisement in newspapers to pay £100 to anyone who bought and used “smoke ball” as instructed and who contracted influenza. Is the advertisement an offer that becomes binding if someone bought the ball? Did the defendant reasonably appear to intend to give all readers of the advertisement that power? What fact did Lindley LJ think was crucial? See p. 124 bottom. Livingstone v. Evans, p. 126. (1) S offers land to B for $1800 (2) B counter-offers $1600 and asks S for his lowest price. (3) S replies “Cannot reduce price.” (4) B accepts original offer. Is there a contract? Did B reasonably believe initial offer was still on the table when he accepted? Why? Re Cowan & Boyd, p. 127. Landlord offers to renew lease at increased rent. Tenant rejects and offers to renew at current rent. Landlord responds he will visit to talk the matter over. Walsh says this is a harder case. Why? An offeror is presumed to have the power to revoke an offer. Generally an offer is irrevocable only if the offeror explicitly promises to hold offer open and there is a legal basis for enforcing the promise, including •Consideration •UCC § 2-205 (firm offer for sale of goods in writing signed by merchant)* •Promissory estoppel/reliance * Binding for a reasonable time not more than 90 days. In European law there is a general rule that such a commitment is binding. See Unidroit Article 2.1.4(2)(a). And an offer stating a fixed time for acceptance is interpreted as a firm offer. CISG Art. 16(2)(a); Principles of European Contract Law 2.202(3)(b). Adams v. Lindsell, p. 131. D mails an undated offer that is mis-addressed and so delivered late. P mails immediate acceptance. D sells goods in interim. The contract is formed when P mails the acceptance. This is called “the mailbox rule.” P’s power to accept would be terminated if D communicated the fact it had sold goods to another before P accepted and P received this communication. Rules on offer and acceptance determine assent when parties communicate by post or other remote means. Many of these are background rules. They can be altered by a clear expression to the contrary. Other rules determine assent in other situations, such as the effect of a preliminary agreement when execution of a written contract is contemplate. Statute of Frauds Types of agreements “within” the statute include (there are others) . . . A sale or other conveyance of an interest in land (with an exception for short-term leases). See p. 145 top. A sale of goods of sufficient price--10 pounds in Statute of 1677. Now $500 under § 2-201 of the Uniform Commercial Code. See p. 145 bottom. Statute provides a defense to a claim on a contract if there is not sufficient written evidence of the contract. Section b p. 146 indicates there is a difference on what it takes to satisfy the statute. UCC 2-201 takes a minimalist approach. Any writing signed by the party trying to assert the statute as a defense that is “sufficient to indicate that a contract for sale has been made . . .” Only the quantity need appear in the writing. Often in real estate law there is a requirement that the writing state the “essential terms.” Purposes served by the statute of frauds and by contract formalities more generally . . . •Evidentiary •Cautionary •Channeling These purposes assume legal formalities serve to enable people to determine their legal obligations for themselves. Statute of frauds provides a defense to an otherwise enforceable agreement for a contract “within the statute” in the absence of a writing “to satisfy” the statute. UCC 2-201(3)(pp. 145-146) provides several grounds to overcome the defense: • By admission • Part performance (payment made and accepted or goods received and accepted) • Substantial investment in specially manufactured goods Two of these exceptions can be explained on evidentiary grounds. The last exception brings to mind a nonstatutory exception with another rationale . . . Goldstein v. McNeil (Cal. App. 1954), p. 147 (pre-dates enactment of UCC). Oral sales agreement for 14 used cars for a price of $29,450. The buyer (the defendant) paid the seller (the plaintiff) $910 for shipping costs. The seller spent $210 on permits and shipped the cars to California. Held defendant was estopped from asserting statute of frauds as a defense because of plaintiff’s change of position and inequity (“unconscionable loss”) that would result from enforcing statute. The loss was due to the drop in the price of used cars! Goldstein v. McNeil (Cal. App. 1954), p. 147 Oral sales agreement for 14 used cars for a price of $29,450. The buyer (the defendant) paid the seller (the plaintiff) $910 for shipping costs. The seller spent $210 on permits and shipped the cars to California. The claim was not within the statutory exceptions, which required that the goods be received and accepted or that the buyer have made part payment for the goods. See p. 147 top for provisions. Estoppel is a non-statutory exception. Obligation in contract requires 1) 2) 3) An apparent expression of intent to undertake an obligation (e.g., by promise, agreement, offer & acceptance . . .) A legal basis for enforcing the obligation such as consideration. Sometimes written evidence of the obligation under the statute of frauds. In the US reliance—perhaps even a foregone opportunity— can supply 2) and overcome 3).