Read Presentation

advertisement

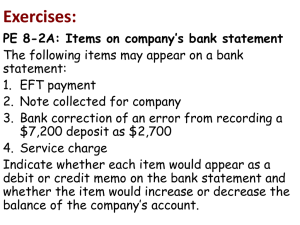

A CLOSER LOOK AT “LEGAL” RECONCILIATION 35(1) AND THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA 1982 TO 2011 WAS ONLY THE BEGINNING Outline • Apology • The concepts of “legal” and “social” reconciliation • “Legal” reconciliation as a Common Law process • “Legal” reconciliation as a process outside the Courts • Conclusions Apology • My topic is not exactly that provided to Insight • My retirement project is slowly writing a book on the Canadian doctrine of Reconciliation • Research is ongoing • Lot of history, case law, legal, political science, philosophical, anthropological and other commentary to read • By 2009, I concluded the Doctrine of Reconciliation is “complex” Apology • The doctrine consists of at least two inter-related and mutally inter-dependent aspects • “Legal” reconciliation – reconciling indigenous and nonindigenous law in the context of an ongoing Canada • “Social”reconciliation – reconciling indigenous societies with non-indigenous society in same context • I did agree to talk about both today • Closer analysis suggests “legal” reconciliation is also “complex” – I am still fathoming that complexity • So today, I offer some thoughts on “legal” reconciliation • Maybe in 2012 I can offer some thoughts derived from looking more closely at “social” reconciliation. “Legal” and “Social” Reconciliation • The Constitution Act 1982, Section 35(1) is a practical starting point • 35(1) legally was almost entirely obscure in 1982 • By 2004, 35(1) rights were mostly legally “absorbed” into Common Law by SCC decisions • “Absorbed” in sense that legal treatment of 35(1) rights became legally predictable “Legal” and “Social” Reconciliation • SCC says the central meaning of 35(1) is “reconciliation” • “Reconciliation” of laws achieved by SCC expressly stated and other legal processes ; and • “Reconciliation” of societies achieved (with legal assistance) in “new relationships” of innovative social policy “Legal” Reconciliation as a Common Law Process • In 1982, the politicians had not the time, inclination or knowledge to work out the meaning of 35(1) • That project was assigned to the judiciary • Defining the place of 35(1) “existing aboriginal and treaty rights” was entrusted to the rational processes of the Common Law “Legal” Reconciliation as a Common Law Process • The Common Law can “absorb” previously unknown unique rights • “Absorb” does not necessarily mean “extinguish” • “Absorb” means render rights from outside the Common Law into part of the Common Law • “Absorption” is only part of “legal” reconciliation • Long known to legal historians but not called “reconciliation” “Legal” Reconciliation as a Common Law Process • Legal history provides interesting insights into how the Common Law deals with unique Customary Law • Medieval England was divided among about 26,000 manors • Each manor had its own courts and legally binding Customary Law • Most of the wealth and population was located on manors and controlled by local Customary Law “Legal” Reconciliation as a Common Law Process • The Common Law of the central Royal Courts that bound all Englishmen in respect of issues of law and equity determined by them was separate from the Customary Law of the manors that defined most important everyday rights for almost all Englishmen • Most everyday rights depended upon binding custom which could be found locally in written manorial court records and in the testimony of the oldest people living in the manor (elders). “Legal” Reconciliation as a Common Law Process • By 1922, nothing remained of all such Customary Law • For about 500 years, starting in the 15th century, cases relating to Customary Law increasingly appeared in the Royal Courts of Common Law and Equity • The Royal Courts made order out of the mass of sui generis Customary Law • The Royal Courts’ great authority made their decisions preferable to the manor records, the memory of elders and local judgements “Legal” Reconciliaton as a Common Law Process • The primary rational process of the Common Law is to find legal principles that fairly govern similar but unique legal circumstances • This process allowed for the “absorption” and eventual extinction of manorial Customary Law • Rights under manorial Customary Law had no 35(1)-type protection – last ones were extinguished by statute in 1922 • This rational process of absorption is a part of “legal” reconciliation in Canada “Legal” Reconciliation as a Common Law Process • For Example: • Guerin (1984) one aboriginal right found to be sui generis so as to define for the Common Law the legal nature of all aboriginal rights • “Sui generis” is not an insult, it is the rational Common Law mechanism for absorbing the legally unique and previously unknown • Sparrow (1990) one sui generis aboriginal right used to define how all such rights can be infringed by adapting existing administrative law concepts to Crown/Indigenous relations “Legal” Reconciliation as a Common Law Process • Sparrow emphasizes negotiation, not reconciliation – no S. African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (“TRC”) had happened by 1990 • Van der Peet (1996) decided only “distinctive features” within indigenous Customary Law are 35(1) constitutionally protected rights • 35(1) rights derive from Customary Law but procedural and substantive Customary Law detail is neither constitutionally protected nor necessarily extinguished “Legal” Reconciliation as a Common Law Process • Gladstone (1996) The Common Law ignores Customary Law’s internal controls on a 35(1) protected right in favour of limitation on the 35(1) right by regulation • 1996 was after the TRC, so the concept of “reconciliation” was enunciated to be the fundamental to meaning of 35(1) “Legal” Reconciliation as a Common Law Process • Haida (2004) Systematically explains 35(1) in the context of reconciliation • Crown assertion of sovereignty engaged the honour of the Crown in a complex endlessly ongoing reconciliation process • Examples of that process include • (i) negotiation of treaties • (ii) justification by consultation and accommodation “Legal” Reconciliation as a Common Law Process • (iii) establishment of specialized regulatory schemes to judge adequacy of consultation • (iv) establishment of guidelines re claims • (v) negotiation( as preferable to litigation) • (vi) the ongoing operation of the Common Law through litigation of 35(1) rights • List heavily weighted to “legal” reconciliation, mechanisms to “absorb” indigenous Customary Law – far from complete! “Legal” Reconciliation as a Common Law Process • Express recognition of what general administrative law principles have to teach about procedurally fair dealing with 35(1) rights • Description of the spectrum of the required depth of consultation appropriate to facts • Description of tests of “correctness” for consultation process and “reasonableness” for administrative decisions derived from consultation “Legal” Reconciliation as a Common Law Process • Delgamuukw (1998) Application of principles adopted for personal property in pre-1998 cases to real property with different tests for existence and limitations • Normal Common Law treatment of real property being different from personal property • Mikisew Cree (2005) Modern treaty terms are subject to Common Law principles of contract • Both cases demonstrate “legal” reconciliation according to the ancient, rational Common Law “absorption” process “Legal” Reconciliation as a Common Law Process • Little Salmon (2010) General administrative law applies to Crown relations with all Canadians • Specialized “indigenous reconciliatory administrative law” also applies to Crown relations with indigenous Canadians • When will “indigenous reconciliatory administrative law” appear in Canadian administrative law texts? “Legal” Reconciliation as a Process Outside the Courts • “Legal’ Reconciliation is not all about proving and of 35(1) rights and dealing with infringement • “Legal” Reconciliation is a very long term process – 35(1) guarantees rights “forever” • It includes the legal processes expressly contemplated in Haida • Common Law has not given constitutional protection to all rights extant under indigenous Customary Law but has not necessarily extinguished all constitutionally unprotected Customary Law “Legal” Reconciliation as a Process Outside the Courts • We should not be blinded by the grandeur and authority of the “Royal Court”, today, the SCC • “Legal”Reconciliation can happen anywhere, not just in Ottawa • We need to look more closely at legal mechanisms of reconciliation not mentioned by the SCC • Surviving indigenous Customary Law has a place in the everyday life of indigenous and the understanding of non-indigenous Canadians “Legal” Reconciliation as a Process Outside the Courts • Why? • Reconciliation of individuals and groups is a profound human process • Like “love” or “hate”, it has been known in all times and in all places • Reconciliation seems to rely upon mutually understood truths that allow individuals and groups to understand each other better and be “reconciled” • This applies to finding truth in respect of legal systems as much as the traditional reconciliatory processes of finding truth, regret, apology and forgiveness “Legal” Reconciliation as a Process Outside the Courts • The best efforts of Canadian judges have produced a relatively comprehensive system of high-level “legal” reconciliation relating to protected 35(1) rights • It is not going to change much – precedent is precedent • “Indigenous reconciliatory administrative law” is a high level, truth-seeking, reconciliatory formula that may need administrative reforms to work more smoothly – (remember Haida) “Legal” Reconciliation as a Process Outside the Courts • “They who forget history are doomed to repeat it” • Note the former dominance of sui generis manorial law and its total disappearance • Note early medieval Italy where each person was governed by the laws of his or her ancestors while in the same communities – for centuries • Note that indigenous Customary Law based on family unity and peace is very similar to early Anglo-Saxon Customary Law based on family unity and peace – family wanes as state waxes “Legal” Reconciliation as a Process Outside the Courts • Note that the Norman invaders of England became expert in and generally applied indigenous English law and their subjects recognized that law as “legitimate” • “Legitimacy” of law is another “profound” concept – humans are comfortable with just laws of their own making but resist even just laws that are imposed from outside their traditions • See how much support you could get for replacing the Common Law with Civil Law in Canada, the U.K., the U.S., India, Australia, New Zealand etc. “Legal” Reconciliation as a Process Outside the Courts • Note the wisdom of the Truth and Reconciliation Commissions in 40 countries as of 2009 • Reconciliatory processes have not allowed entire populations to forgive and forget but can greatly reduce the “unforgiveness” of large parts of divided populations • Much reconciliation is about healing the dignity of the victim and, thereby, restoring the dignity of the oppressor “Legal” Reconciliation as a Process Outside the Courts • Note that world history knows of many groups reduced to hereditary underclass status • Helots of Sparta • Dalits of India • Burakumin of Japan • Cagots of France • Many Afro-Americans • Note the growth in the Canadian indigenous population but an educational failure to maximize its potential, and thereby its dignity, risks hereditary underclass status for many indigenous people in Canada “Legal” Reconciliation as a Process Outside the Courts • The stakes are high in achieving the profound “Reconciliation” promised by 35(1) • Thinking about how to achieve such profound “Reconciliation” is worthy of careful thought • Hence “peeling the reconciliation onion” into its inter-related “legal” and “social” parts • Hence starting with the question, “After SCC high level analysis, what can be done to achieve “legal” reconciliation?” “Legal” Reconciliation as a Process Outside the Courts • There will inevitably continue to be 35(1) cases in the SCC - but less, given predictable results • Canadian governments need to create comprehensive and reasonably uniform codes relating to appropriate consultation • “Consultation” cases should go to new specialized tribunals to which the courts can defer “Legal” Reconciliation as a Process Outside the Courts • Federal legislation needs to replace the Indian Act with modern dignified legislation that does not erode the dignity of both indigenous and non-indigenous Canadians • Changing the name would be a start • At least the federal ministry has now changed its name “Legal” Reconciliation as a Process Outside the Courts • The making of modern treaties is enormously difficult • The final result can be legally almost unintelligible • There has been “game playing” – translations • As noted yesterday, for some First Nations, entering into a tready has become an unattractive option • The whole theory and practice of modern treaties may need a re-think “Legal” Reconciliation as a Process Outside the Courts • Those developing effective local indigenous governance systems can learn from the lessons of history • Band government under the Indian Act has often been corrupt, not respected and uncomfortable as not “legitimate” for the people living with it day to day • History suggests reform of governance structures based on legitimacy through flexible use of sui generis Customary Law dovetailed with modern transparent governance techniques “Legal” Reconciliation as a Process Outside the Courts • One size does not fit all • Sui generis is not an insult it is a fact of life • The detail of Customary Law does not have to be constitutionally protected to work in the daily lives of people who treat it as legitimate and find it comfortable • Modern transparent governance techniques could economically be based on multi-community institutions providing regular audit functions “Legal” Reconciliation as a Process Outside the Common Law • The lesson that family-based indigenous law parallels the kindred-based law of the ancestors of non-indigenous Canadians is a truth that lends mutual understanding and, thereby, mutual dignity to acceptance of innovative indigenous governance and justice structures • Waning of Family and waxing of State has been too sudden and can be reversed “Legal” Reconciliation as a Process Outside the Courts • The lesson of early medieval Italy and the long toleration of different legal systems working next to each other while slowly growing together suggests that modern governance structures be flexible, be subject to comfortable reform and can be understood by non-indigenous Canadians • Immutable laws ignore progress and presage isolation and underclass status • The time horizon of reconciliation is forever “Legal” Reconciliation as a Process Outside the Courts • “New Relationships” entail a mass of legal documentation somewhat like traditional international diplomatic forms: • IBAs started some of the earliest “new relationships” • Modern indigenous peoples legislation (FN Finacial Transparency Act etc.) • Memoranda of understanding • Resource revenue sharing agreements • Reconciliation agreements • Land use legislation • Specific Claims reform etc. etc. • All are but examples of “legal” reconciliation outside the Courts Conclusions • • • • Reconciliation must succeed The stakes are too high to fail Reconciliation is complex and needs analysis “Legal” reconciliation needs to move on from SCC Common Law “absorption” of 35(1) rights • “Legal” reconciliation needs to be creatively applied as an ongoing process outside the courts • Such application should always respect and be guided by the “profound” nature of reconciliation in both its inter-related aspects if it is to be profoundly reconciliatory