Michiel Coxie

advertisement

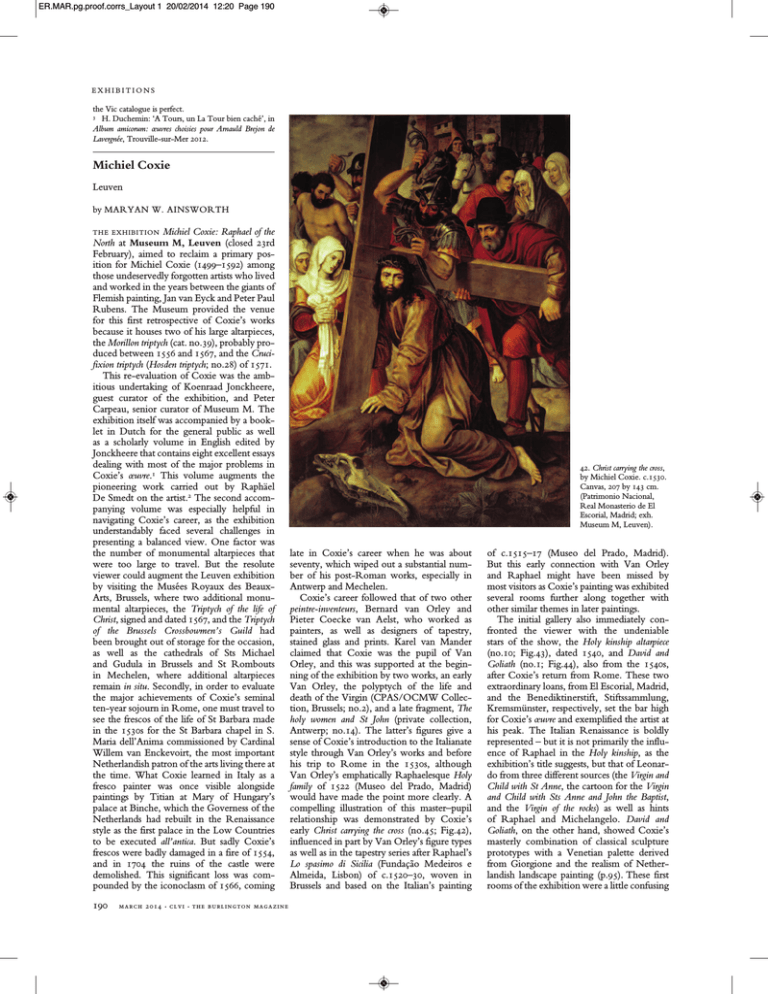

ER.MAR.pg.proof.corrs_Layout 1 20/02/2014 12:20 Page 190 EXHIBITIONS the Vic catalogue is perfect. 3 H. Duchemin: ‘A Tours, un La Tour bien caché’, in Album amicorum: œuvres choisies pour Arnauld Brejon de Lavergnée, Trouville-sur-Mer 2012. Michiel Coxie Leuven by MARYAN W. AINSWORTH THE EX HIBITIO N Michiel Coxie: Raphael of the North at Museum M, Leuven (closed 23rd February), aimed to reclaim a primary position for Michiel Coxie (1499–1592) among those undeservedly forgotten artists who lived and worked in the years between the giants of Flemish painting, Jan van Eyck and Peter Paul Rubens. The Museum provided the venue for this first retrospective of Coxie’s works because it houses two of his large altarpieces, the Morillon triptych (cat. no.39), probably produced between 1556 and 1567, and the Crucifixion triptych (Hosden triptych; no.28) of 1571. This re-evaluation of Coxie was the ambitious undertaking of Koenraad Jonckheere, guest curator of the exhibition, and Peter Carpeau, senior curator of Museum M. The exhibition itself was accompanied by a booklet in Dutch for the general public as well as a scholarly volume in English edited by Jonckheere that contains eight excellent essays dealing with most of the major problems in Coxie’s œuvre.1 This volume augments the pioneering work carried out by Raphäel De Smedt on the artist.2 The second accompanying volume was especially helpful in navigating Coxie’s career, as the exhibition understandably faced several challenges in presenting a balanced view. One factor was the number of monumental altarpieces that were too large to travel. But the resolute viewer could augment the Leuven exhibition by visiting the Musées Royaux des BeauxArts, Brussels, where two additional monumental altarpieces, the Triptych of the life of Christ, signed and dated 1567, and the Triptych of the Brussels Crossbowmen’s Guild had been brought out of storage for the occasion, as well as the cathedrals of Sts Michael and Gudula in Brussels and St Rombouts in Mechelen, where additional altarpieces remain in situ. Secondly, in order to evaluate the major achievements of Coxie’s seminal ten-year sojourn in Rome, one must travel to see the frescos of the life of St Barbara made in the 1530s for the St Barbara chapel in S. Maria dell’Anima commissioned by Cardinal Willem van Enckevoirt, the most important Netherlandish patron of the arts living there at the time. What Coxie learned in Italy as a fresco painter was once visible alongside paintings by Titian at Mary of Hungary’s palace at Binche, which the Governess of the Netherlands had rebuilt in the Renaissance style as the first palace in the Low Countries to be executed all’antica. But sadly Coxie’s frescos were badly damaged in a fire of 1554, and in 1704 the ruins of the castle were demolished. This significant loss was compounded by the iconoclasm of 1566, coming 190 mar ch 2 0 1 4 • c lvi • t he b u rl in g t on ma ga zi ne 42. Christ carrying the cross, by Michiel Coxie. c.1530. Canvas, 207 by 143 cm. (Patrimonio Nacional, Real Monasterio de El Escorial, Madrid; exh. Museum M, Leuven). late in Coxie’s career when he was about seventy, which wiped out a substantial number of his post-Roman works, especially in Antwerp and Mechelen. Coxie’s career followed that of two other peintre-inventeurs, Bernard van Orley and Pieter Coecke van Aelst, who worked as painters, as well as designers of tapestry, stained glass and prints. Karel van Mander claimed that Coxie was the pupil of Van Orley, and this was supported at the beginning of the exhibition by two works, an early Van Orley, the polyptych of the life and death of the Virgin (CPAS/OCMW Collection, Brussels; no.2), and a late fragment, The holy women and St John (private collection, Antwerp; no.14). The latter’s figures give a sense of Coxie’s introduction to the Italianate style through Van Orley’s works and before his trip to Rome in the 1530s, although Van Orley’s emphatically Raphaelesque Holy family of 1522 (Museo del Prado, Madrid) would have made the point more clearly. A compelling illustration of this master–pupil relationship was demonstrated by Coxie’s early Christ carrying the cross (no.45; Fig.42), influenced in part by Van Orley’s figure types as well as in the tapestry series after Raphael’s Lo spasimo di Sicilia (Fundação Medeiros e Almeida, Lisbon) of c.1520–30, woven in Brussels and based on the Italian’s painting of c.1515–17 (Museo del Prado, Madrid). But this early connection with Van Orley and Raphael might have been missed by most visitors as Coxie’s painting was exhibited several rooms further along together with other similar themes in later paintings. The initial gallery also immediately confronted the viewer with the undeniable stars of the show, the Holy kinship altarpiece (no.10; Fig.43), dated 1540, and David and Goliath (no.1; Fig.44), also from the 1540s, after Coxie’s return from Rome. These two extraordinary loans, from El Escorial, Madrid, and the Benediktinerstift, Stiftssammlung, Kremsmünster, respectively, set the bar high for Coxie’s œuvre and exemplified the artist at his peak. The Italian Renaissance is boldly represented – but it is not primarily the influence of Raphael in the Holy kinship, as the exhibition’s title suggests, but that of Leonardo from three different sources (the Virgin and Child with St Anne, the cartoon for the Virgin and Child with Sts Anne and John the Baptist, and the Virgin of the rocks) as well as hints of Raphael and Michelangelo. David and Goliath, on the other hand, showed Coxie’s masterly combination of classical sculpture prototypes with a Venetian palette derived from Giorgione and the realism of Netherlandish landscape painting (p.95). These first rooms of the exhibition were a little confusing ER.MAR.pg.proof.corrs_Layout 1 20/02/2014 12:20 Page 191 EXHIBITIONS 43. Holy kinship altarpiece, by Michiel Coxie. 1540. Canvas, 245 by 191 cm. (Benediktinerstift, Stiftssammlung, Kremsmünster; exh. Museum M, Leuven). – was the theme Coxie as the pupil of Van Orley or the Italianate Coxie? Also included here was the fascinating painting Plato’s cave (Musée de la Chartreuse, Douai; no.3), which brought into focus an important Platonic and Neo-platonic art-theoretical argument of the early sixteenth century (pp.73–79). However, the attribution of the painting to Coxie is very much in dispute, a matter not resolved by the secure authorship of the other paintings in this room. The second half of the 1530s in Rome experienced a significant increase in printmaking in which Coxie took part by designing various series. Still debated is his authorship of designs for a series of Cupid and Psyche, but unquestionably accepted are the ten drawings that he made for the Loves of Jupiter (British Museum, London; no.17), and these sheets were splendidly on view along with the associated engravings by Agostino Veneziano and the so-called Master of the Die. Coxie as a designer of stained glass was briefly acknowledged in the adjoining gallery. Following Van Orley’s death in 1541, Coxie assumed the responsibilities for the designs of the windows for the Chapel of the Miraculous Sacrament in Sts Michel et Gudule, Brussels. This earned him further commissions from the Habsburg court for Brussels (no.12) and for the Church of St Bavo in Ghent, which was illustrated through a few sketches and drawn copies after the windows (no.13). Compared to the œuvre of Coxie’s contemporary Pieter Coecke van Aelst, there are far fewer preparatory drawings so far identified. The introduction of Coxie as a draughtsman in this exhibition will no doubt lead to new discoveries. Coxie’s production as a tapestry designer was introduced by two splendid examples from the Patrimonio Nacional in La Granja and in Madrid’s Palacio Real, The rape of Ganymede (no.21) from the Ovid or Poesie series, and Queen Thomyris has the decapitated head of Cyrus dipped in blood (no.25) from the Cyrus series. These were beautifully installed in a room with the requisite expansive walls. Here were also an exquisite tapestry cartoon, Scipio landing in Africa (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; no.22), a cartoon fragment, Head of a man (no.24), for the Reunion of Pompey and Cornelia in the Caesar series,3 and a preparatory drawing for Abraham and Lot dividing the lands (no.23), the last two from private collections in Brussels. As Thomas Campbell pointed out in the 2002 exhibition Tapestry in the Renaissance: Art and Magnificence, although Coxie worked for the Habsburgs and in the 1550s received a stipend from the city to provide Brussels’ tapestry weavers with cartoons, few of his tapestry designs are documented, mak- ing it difficult to establish the extent of his work in this medium.4 It is fair to say that this room presented more questions than answers concerning this aspect of Coxie’s activities. Missing was any reference to Coxie’s most securely attributed tapestry designs, those for the Genesis series at Wawel Castle.5 The Scipio cartoon has been published as after a design by Coxie,6 but its relationship to those by Giulio Romano in the Louvre,7 for example, should be further discussed. The superb cartoon fragment Head of a man will be presented in the October 2014 exhibition on Pieter Coecke van Aelst at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, as by that artist.8 As Cecilia Paredes has demonstrated, the Ovid or Poesie series, which includes The rape of Ganymede, also has more in common with the style of Coecke than with Coxie,9 especially when compared with Coxie’s drawing of the same theme for the Loves of Jupiter print series, where the dynamic and muscular body of Ganymede is after a model by Michelangelo. Key to the clarification of Coxie’s postRoman painting production and his contribution to Counter-Reformation art are the altarpieces now housed in Museum M (the Morrilon triptych and the Crucifixion triptych or Hosden triptych) and other local Belgian collections. Certainly the question here is to what extent these works of Coxie’s later years (he lived until he fell to his death from scaffolding in Antwerp at the age of ninety-three) are the product of the workshop. Little is known about Coxie’s assistants, although his sons Raphael and Willem were certainly among them, and three others are named as members of the Mechelen painters’ guild (Lodewijk Crowies, Jacus Dauvoers and Shasper Derwoers). A technical examination of Coxie’s works has only recently been initiated by David Lainé which should reveal further information about the habitual methods of Coxie and his workshop. It would be interesting to know, for example, whether, like his teacher Bernard van Orley, Coxie learned and employed aspects of the working procedures of the Italian painters whose style he emulated.10 The last room of the exhibition was devoted to what Coxie is perhaps best known for, that is, his work as a copyist while in the service of the Habsburg courts of Mary of Hungary and Philip II.11 For the former, Coxie had produced a copy of Rogier van der Weyden’s Descent from the cross as compensation to the Crossbowman’s Guild from whom she had acquired the original. After receiving an initial payment in 1556, Coxie began work on a copy of Hubert and Jan van Eyck’s Adoration of the mystic lamb altarpiece for Philip II, which took him two years to complete. In a great coup, the exhibition’s organisers achieved the unimaginable by reuniting all the interior panels of Coxie’s copy from Berlin, Munich and Brussels. Although a number of changes have been introduced (St Cecilia is gone, Coxie himself, Charles V and Philip II appear among the Christian Knights, and the donors t he burli ngton magazin e • clvi • march 2 014 191 ER.MAR.pg.proof.corrs_Layout 1 20/02/2014 12:20 Page 192 EXHIBITIONS Making and Marketing: Studies of the Painting Process in Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century Netherlandish Workshops, Turnhout 2006, pp.99–118. 11 See R. Suykerbuyk: ‘Coxie’s copies of old masters: an addition and analysis’, Simiolus 37/1 (2013–14), pp.5–24. Florence! Bonn by ALISON WRIGHT 44. David and Goliath, by Michiel Coxie. c.1540s. Canvas, 139 by 106 cm. (Patrimonio Nacional, Real Monasterio de El Escorial, Madrid; exh. Museum M, Leuven). and saints on the exterior wings were replaced by the Four Evangelists), Coxie’s copy is remarkably faithful to the original. It would have been equally interesting to have installed in the same gallery Coxie’s copy of Rogier van der Weyden’s Descent from the cross (Museo de Pintura de San Lorenzo de El Escorial, on loan from the Prado, Madrid) to judge more fully the painter’s ability to replicate the style and technique of the two very different Netherlandish masters. After the exhibition the Mystic lamb panels will be studied with infra-red reflectography, which should reveal more fully the details of Coxie’s copying procedures. The ability to study Coxie’s Mystic lamb is timely, as the cleaning and restoration of the Van Eyck panels is currently underway in Ghent by a team of conservators from the Institut Royal du Patrimoine Artistique, Brussels. In the same final gallery were the altarpiece wings of Sts Luke and John the Evangelist that Coxie was commissioned to make in c.1560–65 by the Mechelen painters’ guild to join Jan Gossaert’s St Luke drawing the Virgin in St Rombouts Cathedral. But here Coxie eschewed Gossaert’s eclectic conflation of antique and modern (i.e. Gothic) style in favour of a Raphaelesque High Renaissance mode, which was the direction in which the local painters’ guild was heading. Koenraad Jonkheere and Peter Carpeau are to be congratulated for having brought the œuvre of Michel Coxie to our attention, 192 mar ch 2 0 1 4 • c lvi • t he b u rl in g t on ma ga zi ne and for boldly having raised the questions that remain to be more fully discussed. The exhibition and accompanying publications are sure to promote further inquiries into this important peintre-inventeur who, although clearly renowned in his own time, has undeservedly slipped into obscurity. 1 Michiel Coxcie (1499–1592) and the Giants of His Age. Edited by Koenraad Jonckheere. 208 pp. incl. 231 col. ills. (Brepols Publishers, Turnhout, 2013), €75. ISBN 978–1–909400–14–6. 2 See especially R. De Smedt: ‘Autopsie de Michiel Coxie, Nouveaux horizons bibliographiques 1565–2010’, Revue belge d’archéologie et d’histoire d’art 80/2 (2011–12), pp.1–255. 3 T.P. Campbell: ‘New Light on a Set of History of Julius Caesar Tapestries in Henry VIII’s Collection’, Studies in the Decorative Arts 5/2 (1998), pp.2–39. 4 Idem: ‘Michiel Coxie’, in idem, ed.: exh. cat. Tapestry in the Renaissance: Art and Magnificence, New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art) 2002, pp.394–402. 5 Ibid., pp.397 and 399; and M. Hennel-Bernasikova in ibid., pp.441–47. 6 E. Hartkamp-Jonxis: ‘Een geschilderd patroon voor een wandtapijt met de “Landing van Scipio op de kust van Afrika” uit het midden van de 16de eeuw’, Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum 56 (2008), pp.83–101. 7 See Campbell, op. cit. (note 4), pp.341–49. 8 This cartoon fragment was first attributed to Coecke in ibid., pp.383–84, fig.175. 9 See C. Paredes in ibid., pp.424–28, no.49. 10 On Van Orley and his adoption of Raphael’s and Raphael’s workshop methods, see M.W. Ainsworth: ‘Romanism as a Catalyst for Change in Bernard van Orley’s Workshop Practices’, in M. Faries, ed.: THE PRE-PUBLICITY for the exhibition Florenz! at the Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn (to 9th March), gave little idea of what that exclamation mark might stand for. By the middle of the complex installation, it was safe to say that one cause for exclamation are the exceptional Florentine loans – Botticelli’s Pallas and the Centaur (cat. no.113), Pollaiuolo’s rarely lent Hercules and Antaeus (no.116), the illuminated Medici Pliny (no.70), magnificent even when tucked in a corner, the document of Giotto’s appointment as capomaestro of the cathedral (ex-catalogue), the earliest oval-projected map of the world, the first tapestry to be woven in Florence. At the same time, a more surprising explanation for that exclamation mark emerged: that it signifies ‘everything’, or almost. Gerhard Wolf’s introductory essay to the catalogue registers some deliberate lacunae, but the exhibition nonetheless offers a rapid and remarkable tour through the city’s commercial activities and organisation, its religious movements, its arts (all of them), its greatest poets, humanism, scientific discoveries, leaders and lords, as well as its interpreters and collectors.1 All this unfolds over some six hundred years, for the show only ends in the late nineteenth century when the city relinquished its brief glory as capital of Italy and its last claim to creative invention. From such a panoramic perspective, the exhibition’s emphasis on Florence as a city of constant change is inevitable. The visitor is welcomed to the city, somewhat obtusely, by Giambologna’s Venus ‘Anadyomene’ (no.5) in a bashful face off with Andrea del Sarto’s young St John the Baptist (no.4) and by the life-size portrait of Dante in the 1465 memorial canvas from Florence Cathedral. Domenico di Michelino’s painting (no.1; Fig.45) presents the walled city of the 1460s allegorically illuminated as a Paradise – literally showered with gold highlights cast by the great Divine Comedy in the poet’s hand. It is the earlier Florence of Dante’s era that is then evoked in the succeeding rotundashaped room, which exploits an existing feature of the Kunsthalle’s postmodern architecture to allude to the Baptistery and the cathedral’s crossing. But if the intention is paradisiacal, the peculiarly purgatorial shade of mauve on walls and floor produces a contrary effect, one that not even the reliefs of Astronomy and Building (nos.12 and 13) from the cathedral’s Campanile could combat. Emerging from a medieval corner, which includes the perfectly preserved penitential Crucifixion by Lorenzo Monaco from Altenburg (no.55) and a number of early illuminated Dante manuscripts, visitors find themselves