AP Art History CH. 34

advertisement

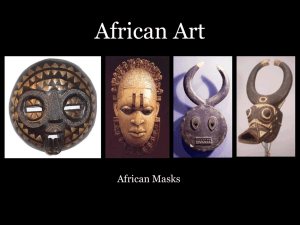

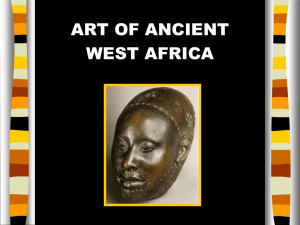

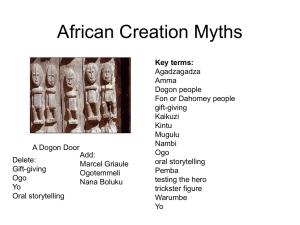

AP Art History CH. 34 By Jessica Dau, Vivian Lee, Catherine Pham, and Victor Pham Period 3 19th Century African Art (Overview) ● Ancient arts of Africans were known for their rock paintings. Similar to the Paleolithic paintings on the caverns. ● Research provided much more detail on the use, function, clarification, and meaning of works produced before the 1800s. ● African arts exist in varied human situations, and knowledge of these contexts is important for understanding these works. San Rock Paintings ● San - People who occupied the southeastern coast of South Africa during early European colonization. Hunters and gatherers. Some raided ranches for livestock and horse. Art centered on animals they pursued. ● ● ● Two San riders on horses drive a herd of cattle and horses toward a San encampment. (Center left of left image). (Right Image far left). Single figure possibly rain maker or diviner leads an enland, an animal considered in rainmaking and rituals, toward the encampment Human leading an animal suggest this motif may represent a ritual leader. Stock Raid with Cattle, horses, encampment, and magical “rain animal,” rock painting (two details), San, Bamboo Mountain South Africa, mid-19th century. Pigments on rock. Fig 34-2 Reliquary Guardian Figure ● Reliquary Guardians play an Important role in Ancestor worship. Africans believed that ancestors provided help for the living, including help in maintaining bountiful crop production ● Ancestor veneration (reverence) takes material form as collections of cranial and other relics such as bones to be gathered in special containers. ● ● ● ● Fang (artist) guardian figures, or bieri, was designed to sit on the edge of a cylindrical bark boxes of ancestral bones, ensuring no harm would befall the ancestral spirits. Guardian is symmetrical, with proportions that emphasize the head, and feature rhythmic buildup of forms that suggest contained power. Proportions of body resemble and enfant, but muscularity of figures indicate adult. Infant and Adult traits to suggest circle of life. Reliquary guardian figure (bieri), Fang, Late 19th Century. Wood 8.75” high. Fig. 34-3 Throne Of Nsangu ● African art also glorifies living rulers. Example: Throne Of King Nsangu. ● ● ● ● ● ● Tensive use of richly colored textiles and shiny materials, such as glass beads and cowrie shells. Intertwining blue and black serpents decorate cylindrical seat of the king’s throne. Two of king’s retainers, constantly at his service. Located above the throne; one man holds a royal drinking horn. Other is a woman carrying a serving bowl. King’s bodyguards are located below wielding rifles. Decorated rectangular footstool are dancing figures. King’s attire/garnishes complement bright colors of seat, showing his wealth and power. Throne and footstool of King Nsangu, Bamum, Cameroon, ca. 1870. Wood, textile, glass beads, and cowrie shells, 5’9” high. Fig 34-5 Nail figure (nkisi n’kondi) D: 1875-1900 P/S: 19th Century A: unknown M/T: Wood, nails, blades, medicinal materials, and cowrie shell. Carved wood(subtractive method), with inserted nails/blades. F: Kongo power figure used by trained priest C: embodied spirits, activated by inserted nails/blades DT: simple anatomical forms, unproportionally large head, face is crude but natural, liberated, smooth (wood) Ideas: held in awe by villagers due to spirits’ ability to inflict of heal harm, figures stood between life and death 20th Century Art ❖ strongly traditional vs. modern African art ❖ gender given roles = men were builder/architects/carvers while women were painters/potters/body painters = collaborated ❖ The 20th century contains nine different styles: Benin, Asante, Yoruba, Senufo, Dogon, Mende, Kuba, Samburu, and Igbo ❖ Benin: most important 20th century artwork (very traditional) ❖ Asante: figures contained long, flattened heads = beautiful ❖ Yoruba: has many skilled artists (Olowe of Ise) Olowe’s artwork contain complex, elongated bodies, fine textures, and the stacking of warriors/weapons/creatures ❖ Senufo: artwork is tied to the community, contains many dancing masks for social,initiation processes,funerary, and public purposes (men wore women masks) ❖ Dogon: specialized in creating cyclical/elaborate masks, human masquerades were dramatized by legends with people wearing spirit/character masks ❖ Mende: women made masks and danced (change from tradition, men danced/wore masks) ❖ Kuba: mostly woven textile masks/clothing which embodied supernatural powers and political power ❖ Samburu: rural areas of eastern Africa where men/women embellished their body with paint ❖ Igbo: creation of houses for sacrificial offerings (still more traditional/little modern) Benin Shrine of Eweka II Material/Technique: base = sacred riverbank clay, copperalloy altarpiece, ivory (elephant tusk) reliefs, wooden staffs, metal bells, bleached white = purity/goodness, Altar to Hand = hierarchy with king at top Function: a royal altar of/for Benin King Eweka II Context: In 1897, the British took over Benin City (this is the only shrine remaining today) Name: Shrine of Eweka II Date: unknown (photographed in 1970) Period/Style: 20th Century, Benin Artist/Architect: unknown Description: similar to earlier shrine versions, heads symbolize the nature of kingship, glistening surface, smooth/red = repel danger and evil, heads = white = purity, tusks = male physical power, wooden staffs = calling royal ancestors/refer to generations, Benin king = wisdom/good judgement/divine guidance of kingdom Ideas: through the sacrifice of animals the king purifies his head/mind through invoking strength from his ancestors Mende Sowie Masks Material/Technique: high/broad forehead = wisdom/success, black shiny coloring, masks are characterized by elaborate coiffures, shiny black coloring, triangularshaped faces with slit eyes, rolls on the neck, actual/carved image of amulets, and emblems at the top Function: evokes female ancestral spirit of the water spirits, masks worn to conceal their bodies from the audience, created with specific societal purposes (debated by carver (men) and the women) Context: Sande women controlled the education/acculturation of young males/females, associated masks with water spirits (the color black) = connects with human skin color/world Name: Sowie Mask Date: unknown Period/Style: 20th Century, Mende Artist/Architect: unknown Description: glistening back surface, mask contains a turtle on top of the “helmet”, signs of beauty/good health/ prosperity = rippling, woven/plaited hair = harmony/ideal order in a household, slit eyes/small mouth = seriousness Ideas: women became masqueraders (not only men = nontraditional), the masks symbolized the adult women’s role of being a wife/mother/provider for the family/medicine keeper, appeal to the ideals of feminine beauty/morality/behavior Samburu Samburu Men and Women Dancing Material/Technique: painted their bodies with red ocher, wore bracelets/necklaces/beaded jewelry made by women, create more elaborate bead necklaces for themselves, available plastics/aluminums, woven textiles Function: unknown however possibly ritual/spiritual/celebratory/coming of age/spouse looking purposes Context: men and women adorned their bodies with ritual paints with distinct personal styles, men who are unmarried warriors spends hours creating elaborate hairstyles Period/Style: 20th Century, Samburu Description: to separate the genders, women shaved their heads and adorned with bead headbands, personal decorations were created as a child, each design symbolized something (ex: age/status/parents/etc.) Artist/Architect: unknown (women did the body paint) Ideas: the Samburu people danced and celebrated their individual characteristic, religious purposes? Name: Samburu Men and Women Dancing Date: unknown (photographed in 1973) Igbo Ala and Amadioha Material/Technique: made from mud (houses), inside of house contains images of frightened/beautiful animals taken from mythology, houses were to never go under repair = return back into earth Function: early civilians created mbari houses, mud houses, every 50 years to make sacrificial offering to their major gods (ex: Ala, goddess of the earth), contained numerous unfired clay sculptures (an example is the picture on the left) Context: This sculpture depicts Ala and the thunder god, Amadioha, this is a new ritual where the house is open to allow the prayer to have his/her prayer heard (unlike Greeks who prayed outside temples which were created for the gods) Name: Ala and Amadioha Description: the houses were very elaborate, god = modern clothing, Ala = traditional body paint/fancy hairstyle, enlarged torsos/necks/heads = Date: unknown (photographed in 1966) aloofness/dignity/power Period/Style: 20th Century, Igbo Artist/Architect: unknown Ideas: the difference in clothing represents Igbo’s traditional views vs. modern views (both were viewed as positive), men were allowed modern attire while women were to be traditional Comparative Analysis 34-9 Seated Couple, Dogon, Mali 34-10 Male and female figures, Baule, Cote d’Ivoire Similarities -Depiction of male and female figure -conceptual representation -unproportional figures to emphasize idealization of culture -both portray nude figures with focus on different genitalia and gender -carved out of wood Differences -Emphasize gender roles in African society *man portrayed as hunter and warrior w/quiver and contact with female breast *woman carries child on back -incised abstract geometric lines and patterns -rhythm and tension flows through forms and negative space -completely anatomically incorrect -figures depict some emotion -spirits or ancestors in shrine/altar -created during 1800-1850 -Portray asye usu (bush spirits) -Created later, during late 19th or early 20th century -elongated necks with enlarged heads and calves -still records naturalistic aspects of human form *curved breasts, individual phalanges, -carved for religious use by diviners also adorned with beads and kaolin -much smaller in size than other work Contemporary Art The art forms of contemporary Africa are immensely varied. However, there are four examples that can give a sense of the variety and vitality of African art today. Dogon Togu Na ● ● ● Under Dogon Togu na , also known as “men's house of words”, traditionalism and modernism intertwine. Recent replacement posts feature a narrative or topical scenes of varied subjects such as horsemen, hunters, or woman preparing food. These artworks include abundant descriptive detail, bright polychrome painting in enamels, and some writing. Unlike earlier traditional sculptors, these artists want to be recognized and are eager to sell their works to tourists. The togu na is also called the ‘men's house of words” because men’s deliberations crucial to community wellbeing took place under its roof. It is considered the “head” and the most important part of the community, which the Dogon characterize with human attributes. Earlier posts, like the picture to the right, show simplified renditions of legendary female ancestors, similar to stylized ancestral couples or masked figures. 34-24 Togu na (men’s house of words), Dogon, Mali, Photographed in 1989. Wood and pigment. Trigo Piula ● ● ● ● The Democratic Republic of Congo’s Trigo Piula was a painter trained in Western techniques and styles. His works fused western and congolese images and objects. A traditional Kongo power figure related with warfare and divination stands at the composition’s center as a visual mediator between the anonymous foreground viewers and the multiple TV images. In traditional Kongo contexts, this figure’s feather headdress links it to a supernatural and magical power from the sky. Such as lightning and storms. Traditional Kongo thinking and color symbolism, the color white and earth tones are associated with spirits and the land of the dead. Ta Tele depicts a group of Congolese citizens staring hypnotized at colorful pictures of life beyond Africa displayed on 14 TV screens. The images include reference to travel to exotic places, sports events, love, the earth seen from a satellite, and wester worldly goods. In Piula’s rendition, headdresses refer to the power of airborne televised pictures. The artist shows most television viewers with a small white image of a foreign object. The television messages have deaded the minds of Congolese people to only modern thoughts or commodities Piula suggests the world’s new television induced consumerism is poisoning the minds and souls of the Congolese people as if by sorcery or magic. 34-25 Trigo Piula, Ta Tele, Democratic Repubic of Congo, 1988. Oil on canvas, 3’ 3.375’’ x 3’ 4.375”. Collection of the artist. Willie Bester ● ● ● ● ● Willie was among the critics of the apartheid system ( government sponsored racial separation). His pictures were packed with references to death and injustice Blood red and ambulance yellow are unifying colors dipped or painted on many parts of the works. Numbers refer to dehumanized life under apartheid. The whole composition is rich in texture and dense in its collage combinations of objects, photographs, signs, symbols, and paintings. Bester’s 1992 Homage to Steve Biko is a tribute to the gentle and heroic leader of the South African Black Liberation Movement whom the authorities killed while he was in detention. Through his piece of work, Bester includes many symbolic images. This portrait memorializes both Biko and the many other antiapartheid activists indicated by the white graveyard crosses above a blue sea of skulls beside Biko’s head. The crosses stand out against a red background that recalls the inferno of burned townships. The stop sign (lower left) seems to mean “stop kruger” or perhaps “stop apartheid.” The tagged foot above the ambulance (to the left) also refers to Biko’s death. The red crosses on the ambulance door and on Kruger’s reflective dark glasses echo, with sad irony, the graveyard of crosses. The oil can-can guitar bottom center), another recurrent Bester symbol, refers both to the social harmony and joy provided by music and the the control imposed by apartheid policies. 34-26 Willie Bester, Homage to Steve Biko, South Africa, 1992. Mixed media, 3’ 7.83” x 3’ 7.85”. Collection of the artist. Kane Kwei and Paa Joe ❖ Kane Kwei ,of the Ga people in Urban Coastal Ghana, created a new kind of wooden casket that brought him both critical acclaim and commercial success. ❖ Kane created figurative coffins intended to reflect the deceased’s life, occupation, or major accomplishments. He made diverse shapes, cows, whales, cars, onions. Using only nails and glue rather than carving. ❖ Kwei’s sons and his cousin Paa Joe have carried on his legacy. In the photo to the right is a 2000 photograph of joe’s showroom in Teshi, prospective customers view the caskets on display, including an airplane and a cow. Only some of the coffins made by Kwei and Joe were ever buried. 34-27 Paa Joe, Airplane and cow coffins in the artist's showroom in Teshi, GA, Ghana, 2000 African Art Today ● During recent decades, invasion of christianity, islam, western education, and market economies have led to a secularization in all the arts of Africa. ● Many figures and masks commissioned for shrines, incarnations of ancestors, and spirits are being sold to outsiders. ● Traditional Values hold considerable force in villages. some people adhere to spiritual beliefs that uphold traditional art forms ● Contemporary African art remains as varied as the vast content itself and continues to evolve.