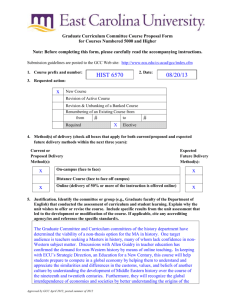

the powerpoint presentation

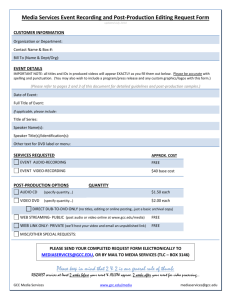

advertisement

Diversified but marginal: the GCC private sector as an economic and political force Steffen Hertog London School of Economics The GCC private sector at first glance • • • • Employs 80% of workers in the region Provides the majority of local capital formation Has deep overseas capital resources Is at the center of all GCC governments’ diversification strategies • Has diversified into new sectors – Telecoms, heavy industry, utilities, aviation… • Is a leading regional investor in MENA • Has matured technologically and managerially BUT • Business activities remain dependent on the state in a variety of ways • It remains economically decoupled from the national population • As a result, it has become marginal in economic policy-making and national politics more broadly The roots of its political marginalization are based on its structural position in the economy It can only regain a more central political role if it establishes organic economic links with the national population Share of state spending in non-oil GDP • • State remains a large, if not dominant driver of demand Boom in 2000s was state-driven Ratio of government to private consumption in GCC and select international cases Drivers of growth • Growth patterns in the private sector at large still broadly follow state spending • No taxes no feedback loop from business growth to state spending growth • Relationship is one-sided: state spending drives business growth, not the other way around Some shifts in the channels of dependence: ratio of capital to current spending in government budgets • Business nowadays profits more from consumer demand (through salaries of state employees) than directly from government contracts • More competitive markets, smoother growth patterns • But still underlying structural dependence on the state: very low private wage ratios (7% in Saudi Arabia e.g.) Contribution to national employment: the state dominates GCC employment structures • Nationals predominantly employed in public sector, with better wages and work conditions Growth of business mostly benefits foreign labor • “Jobless growth” for nationals in the 2000s – Huge imports of foreign workers • Local companies often perceive employment of nationals as a burden and, when obligatory, a tax. • Much popular disenchantment with business class • Best, most productive jobs for nationals are usually in SOEs, not private sector • Foreign workers remit most of their income abroad, further reducing the contribution of business to national demand generation/growth Business dependence on non-fiscal state support • Cheap capital, energy and infrastructure • Incentivizing resource-intensive, low-tech development • Increasing consumption rivalry with residential consumers as gas become scarce Low contributions to knowledge economies and innovation • Factor-intensive growth: – Cheap, low-skilled labor – Cheap energy inputs limited incentives to acquire technology Stagnant or declining productivity Few jobs that pay living wages for nationals Share of hi-tech exports in total manufacturing exports (%, 2009) • • Practically no R&D in the private sector Technology development driven, if at all, by SOEs (Mubadala, SABIC, Aramco etc.) Corporate governance and the public’s exclusion from private sector wealth • Patrimonial, family-based nature of most private wealth tends to lead to – Corporate governance deficits • Saad and Gosaibi • Companies with strongest corporate governance are usually SOEs – Exclusion of the public from investment opportunities in the private sector • Most large groups are privately held, most “blue chips” on local stock markets are former SOEs Another factor decoupling citizens and business The role of business in economic policy-making • In line with the private sector’s dependent economic position, lobbying tends to be reactive and piecemeal – Defense of privileges (subsidies, agencies, fighting taxes, fees and labor nationalization rules etc.) rather than proactive policy initiatives • Chambers of Commerce dominated by big families – limited policy research capacity – Limited activation of broader business community The structural position of GCC business: • isolated from the citizenry at large, for which it provides – – – – Little employment, No taxes, Limited investment opportunities, and with which it competes for increasingly scarce low-price goods and services provided by the distributive state How is this decoupling/rivalry in the political realm? The decline of merchant elites as a political players • Used to lead nationalist and parliamentary movements in 1920s to 1960s – Especially in pre-oil era, when they provided taxes, infrastructure, local employment • Now marginalized in parliaments all over the GCC – Present as government clients, if at all • Also marginalized as social, “notable” elites – Partially the natural result of the emergence of mass politics and society as in rest of MENA – But also due to the absence of shared economic interests with citizens at large • No scope for a historical “class compromise” as e.g. in Europe Fiscal sociology of a tax state Fiscal sociology of an authoritarian rentier state – government as arbiter Dubai as example (cf. Michael Herb) Fiscal sociology of a participatory rentier state – one-sided pressure Kuwait as example (cf. Michael Herb) The future • The majority of nationals all across the GCC continues to have no significant stake in private sector growth. • In the long run, a zero-sum distributional conflict is set to grow – demands on state resources will become ever larger due to growth of both business and the national population. • In a fiscal crisis, popular interests will likely be privileged over business interests, even in authoritarian rentiers – Business provides little that is essential for regimes’ survival – Precedent of 1980s and 1990s Can business do anything about it? • Yes, but it could be costly: – Accept taxation at least in principle – Reform corporate governance and give up exclusive control of assets – Most of all: step up employment of nationals • focus on technological upgrading, build local human resources • requires policy changes beyond the control of business, e.g. a reduction in public sector over-employment • Stronger local employment & taxation would reduce business profits in the short run, • But it could give business a much safer and more autonomous political position in the long run – It could become a true bourgeoisie capable of negotiating with state and other social forces – The best weapon against parliamentary populism?