What a way to make a living

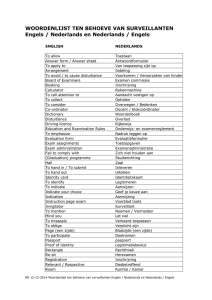

advertisement