Non-randomised studies

Methodologies for a new era summer school

School of Applied Social Studies, University

College Cork

22 June 2011

Dr Paul Montgomery

Jennifer Burton

Why bother?

The data from a good study can be analysed in

many ways, but no amount of clever analysis

can compensate for the problems with the

design of a study.

(Altman, 1991)

Introduction

It is sometimes impossible or undesirable to

influence events in a human sample

You may not be able to control group allocation

It may be unethical to expose or withhold an

intervention

An appreciation of the varieties of study

designs available can reduce the need

to reinvent the wheel and to rediscover

the mistakes of others. It can also help

to end the “scandal of research”’

(Altman, 1993)

Aims

Identify types of questions that can be answered

using non-randomised methods

Describe several non-randomised designs

Highlight the strengths and weaknesses of

common non-randomised designs

Question to design

Prevalence/ incidence

Risk and protective factors

Prognosis

Harm

Effectiveness

Nature,

prevalence of

social problem

Systematic

Reviews and

Meta-Analyses

Intervention

Trials:

Efficacy

Risk,

protective

factors

Intervention

Trials :

Effectiveness

Practice

Guidelines

Evidence Based Practice:

Judicious application of

research to individual

clients and organisations

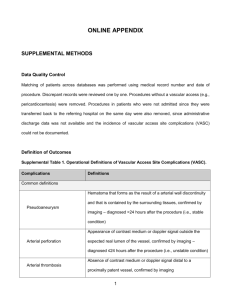

The Hierarchy of Evidence

For Intervention Studies

Meta-Analysis of Randomised Trials

Randomised Trials

Internally

Valid

Evidence of

Effectiveness

Non-randomised studies

Cohort studies

Case-Control studies

Non-comparative studies

Illustrative examples,

hypothesis generating studies

Case Series (open trial)

Case reports

Expert opinion

Question to Design

In practice, methods tend to be

complementary in answering questions

Each method may be used to answer

several types of questions

Several studies may help tease apart a

question

Prevalence

How many people have mental health disorders?

Surveys

Census (one-time full population)

Ideal but expensive, difficult, likely to miss people

from marginal groups

Cross section (one-time sample)

Must consider many potential biases due to

geography, time, etc.

Cross-Sectional Survey

Identify a sample of adults

representative of the population

Measure symptoms of mental health

problems

Calculate the number of people above a

given threshold

Surveys

Usefully estimate prevalence or incidence and

associations

Comparisons may be made between different

subgroups to identify associations

Risk and Protection

Does smoking cause cancer?

Risk and Protection

What factors

can predict

falls in the

elderly?

Retrospective Cohort

Take all elderly people in Oxford

Look at

Characteristics of their homes

Individual factors (e.g. medication use)

Other predictors?

Look for association between these

factors and falls

Retrospective Cohort

Backward looking survey

Relatively inexpensive and practical

Good for detecting latent outcomes

Prone to several sources of bias (selection,

participant recall, etc.)

Risk and Protection

What are the factors that contribute to chronic

fatigue syndrome?

Prospective Cohort

Take all babies born in a given period in

1970

Survey them regularly

Look for correlations between variables

(e.g. maternal depression) and

outcomes (e.g. chronic fatigue)

Prospective Cohort

Identifies temporal relationships

Can examine multiple effects of exposure

Loss-to-follow-up can be a problem

Inefficient for the evaluation of rare problems

unless the attributable risk is high

e.g. 1970 British Cohort Study (ongoing)

http://www.cls.ioe.ac.uk/

Risk and Protection

Is fish oil good for my mental health?

Ecological Studies

Compare countries’ consumption of

fish oil to their rates of depression

Increased consumption of fish oil

lowers a nation’s rate of depression

(Hibbeln 2001), but eating fish is not

the only difference among countries

Ecological Studies

Large unit of analysis (e.g. countries)

May identify population-level risk and protective

factors

Because the unit of observation is not the

individual subject, they are subject to the

ecological fallacy when they overlook important

sources of variance

Risk and Protection

Is running bad for my knees?

Case Control

Identify a group of runners

Then find a group of people who don’t

run matched for age, sex, weight and

other variables

Test for associations between knee

problems and being a runner

Case Control

Inexpensive and practical

Good for generating hypotheses

Lacks a temporal dimension

Unless data come from a population-based

survey, cannot give incidence and prevalence

data

Prognosis

My husband has just

taken 4 times the

recommended dose

of purple pills.

What’s going to

happen?

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 60 year old man was prescribed 10 mg of vardenafil

(Levitra, Bayer) for sexual dysfunction. Because this was ineffective,

he increased the dose to 40 mg. Three hours later, he had a tonicclonic seizure, seen by his relatives.

On admission to hospital, neurological examination, brain magnetic

resonance imaging, and electroencephalography after sleep

deprivation were normal. Stress electrocardiography,

echocardiography, and cardiac scan with dipyridamole test as well as

carotid doppler ultrasonography did not show concomitant cardiac

diseases. The man was told to stop using vardenafil.

Two months later he had a new tonic-clonic seizure, four hours after

taking 30 mg of vardenafil. At eight months' follow-up he is seizurefree without treatment.

Pasquale Striano, Federico Zara, Carlo Minetti (professor of paediatrics), Salvatore Striano

(2006). Epileptic seizures can follow high doses of oral vardenafil. BMJ;333:785.

Case Report

Inexpensive and quick

May draw attention to important clinical

and research issues

In rich detail, describes conditions and

outcomes

May not be representative, does not

usually provide evidence of causation

Case Series

Several case studies

Draws attention to patterns in client populations

Common in aetiological research

Break

Effectiveness

Does abstinence education reduce the

likelihood of premarital sex?

Pre-post (single group)

Take a class of kids

Ask them if they will have sex before marriage

They attend an abstinence-based education

programme

Ask them if they will have sex before marriage

Pre-post (single group)

Inexpensive, generally easier than controlled

studies

Provides some evidence of temporal

relationships

Usually lacks a plausible counterfactual (i.e.

what would have happened in the absence of

intervention)

Effectiveness

Does Head Start

improve IQ?

Between Group

Look at all the kids in New York born in

1980 who were eligible for Head Start

Compare those who attended to those

who did not attend

If possible, collect measures before and

after attendance

Between Group

Provides a counterfactual scenario,

can give evidence of temporal

relationships.

Groups may differ on both measured

and unmeasured variables, observed

differences may be attributable to

factors other than the intervention.

Effectiveness

Does having regular contact with a social

worker improve outcomes for fostered

children?

Historical Control

Compare children in foster care since

the 1944 education act to children in

foster care before then.

If possible, include measures before

and after enrolment for children in each

group.

Historical Control

Provides a counterfactual scenario

Groups may differ on both measured

and unmeasured variables, observed

differences may be attributable to

factors other than the intervention

Effectiveness

Do intensive

police

crackdowns

reduce gun

violence?

Time-Series

Identify areas with high levels of gun crime and

identify peak times

Repeatedly use crackdowns during periods of

high crime

Compare times with the intervention to periods

without the intervention

Time-Series

Provides a counterfactual scenario

Times may be different

Often requires complicated statistical

analyses to control for differences in

baseline variables, time trends, etc.

Conclusion

What is your question?

What types of study design might

contribute to an answer?

Think ‘Horses for Courses’