Sarah Czarnecki

advertisement

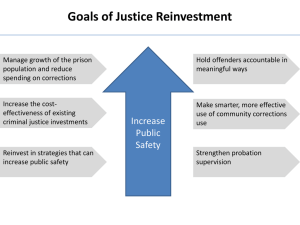

From the ‘social’ to the ‘informational’ in the Probation Service...and back again? Sarah Jane Czarnecki Department of Social Policy and Social Work – University of York sjc520@york.ac.uk Presentation objectives To outline some preliminary findings on a PhD study to ‘map’ the way that offender risk is assessed by probation practitioners To explore whether the study has found evidence that changes in the probation service, including new National Standards, are signalling a return to the ‘social’ in probation practice? Risk and managerialism in the probation service Latter twentieth century and early twenty-first century, arguments that the probation service has become a ‘centrally driven’ law enforcement agency directed towards assessing and managing offender risk with a public protection raison d’être (Raynor and Vanstone, 2007) Led to increase in risk and needs assessment tools aimed towards achieving public protection and managing offender risk (Robinson 2002, Bullock, 2011) Contemporary probation service characterised by a “computerisation; stringent enforcement practices; managerialism and bureaucracy” with a focus on achieving value for money, demonstrating effectiveness and chasing objectives and targets (Whitehead, 2010: 17, 23) Changes in probation practice Early probation service values for practitioners to ‘advise, assist and befriend’ offenders (May, 1991) Parton (2008) argues, probation officers are no longer part of the social work profession with a shift from the terrain of the ‘social’ to the terrain of the ‘informational’ in traditional social work organisations (Parton, 2008: 256) April 2011 roll-out of new National Standards guidelines promoting a move away from the bureaucratic managerially driven approach to offender management to an approach espousing the increased use of professional judgement and discretion in dealing with offenders (http://www.theyworkforyou.com) The PhD research project Qualitative case study of a probation trust in the North of England 6 months – early to mid-2012 Triangulation of research methods:a) Document review – policy, procedures, training guidelines b) Periods of observation of probation practitioners conducting Pre-Sentence Report interviews with offenders c) Semi-structured interviews with same practitioners Research fieldwork (1) – Observing PreSentence Report (PSR) Interviews 22 observation sessions of Pre-Sentence Report interviews between probation officers and offenders – included taking notes on:Physical setting and materials / tools, context, behaviours and interactions, conversations and verbal interactions Research fieldwork (2) – Interviews with probation officers 22 semi –structured interviews with probation officers covering areas including: Background and training Questions about how probation officers make risk assessments and risk decisions Questions about how probation officers feel about carrying out risk assessments and working for the probation service Preliminary findings - Observation sessions 22 one-to-one interviews between probation officer and offender – ranging from 45 minutes to 2 hours in duration Offences ranged from ‘affray’ to ‘production of Class B drugs’ Exploration of offence, offender ‘feelings’ about offence, discussion of impact of offence on community and family, offender family history and current domestic situation, offence related lifestyle issues e.g. drug and alcohol use, motivating factors for offence Discussion of potential sentencing recommendations including community order, unpaid work, curfew, programme requirement Preliminary findings – Interviews 22 interviews ranging from 45 minutes to 1.5 hours duration 18 questions, semi-structured Tape recorded and written notes Preliminary findings – Interview questions and answers Question Which parts of your role involve an element of carrying out risk assessment for offenders on your caseload? -Is risk assessment formal e.g. computer based or informal e.g. conversations with colleagues etc. Preliminary finding All 22 probation officers said that risk assessment comprises a very large part of the role and involves a mix of informal and informal processing Informal risk assessment involves interactions such as discussions with colleagues, information from offender family members, information gained from home visits* Formal risk assessment is captured in use of offender computer case records and multi-agency liaison Question What are the main features that guide you in making risk decisions about offenders? Preliminary finding Answers on this ranged from offender self-reported information, information from police and other agencies and ‘gut instincts’. A recurring thread in interviews was that nearly all probation officers said discussion of offenders with colleagues was an important factor in guiding risk decisions Question How do you feel about the amount of bureaucracy involved in your work? Preliminary finding All officers said there is ‘too much’ bureaucracy and a lot of repetition and duplication of tasks. Four of the 22 specifically mentioned the new National Standards and said that these have not cut down on the bureaucracy Question Has working in the probation service changed since you first joined? - What changes have you noticed? Preliminary finding All of the officers said that there have been changes and there is ongoing change in the probation service in the time they worked for the service (tenure ranged from 7 years to 30+ years) 15 of the officers discussed a culture shift and there being a managerial, business centred focus for probation work 7 pointed specifically to the new National Standards heralding a return to social work values and lessening of bureaucracy Question What aspects of your role give you most satisfaction? Preliminary finding Nearly all (19) focussed on the offender relationship and working with offender to help facilitate change The other 3 mentioned facets of the job such as report writing and collaborative working with other agencies Initial conclusions...is there a discernible return to the ‘social’ New National Standards recurring theme in many of the interviews Movement towards professional judgement and discretion welcomed overall Home visits more prevalent and being encouraged All probation officers highlighted the importance of the key feature of ‘relationship building’ with offenders Still too much reliance on computerised systems in probation work References Blunt, C. (2011), Probation Service (Revised National Standards), http://www.theyworkforyou.com/wms/?id=2011-04-05b.59WS.1 (last accessed 29/02/12) Bullock, K. (2011), ‘The Construction and interpretation of risk management technologies in contemporary probation practice’, British Journal of Criminology. (2011) 51, pp. 120–135 May, T. (1991), Probation: Politics, Policy and Practice, Buckingham: OUP Parton, N. (2008), ‘Changes in the Form of Knowledge in Social Work: From the ‘Social’ to the ‘Informational’?, British Journal of Social Work, 38, pp. 253–269 Raynor, P. and Vanstone, M. (2007), ‘Towards a correctional service’ in Gelsthorpe, L. and Morgan, R. (2007) (eds), Handbook of Probation, Cullompton: Willan Publishing Robinson, G. (2002) ‘Exploring risk management in probation practice: Contemporary developments in England and Wales’, Punishment and Society, Vol 4 (1), pp: 5–25 Whitehead, P. (2010), Exploring modern probation: Social Theory and Organisational Complexity, Bristol: The Polity Press Any feedback is appreciated! Thank you for listening!