Intergenerational Support, Cohesion, and Influence in Later Life

advertisement

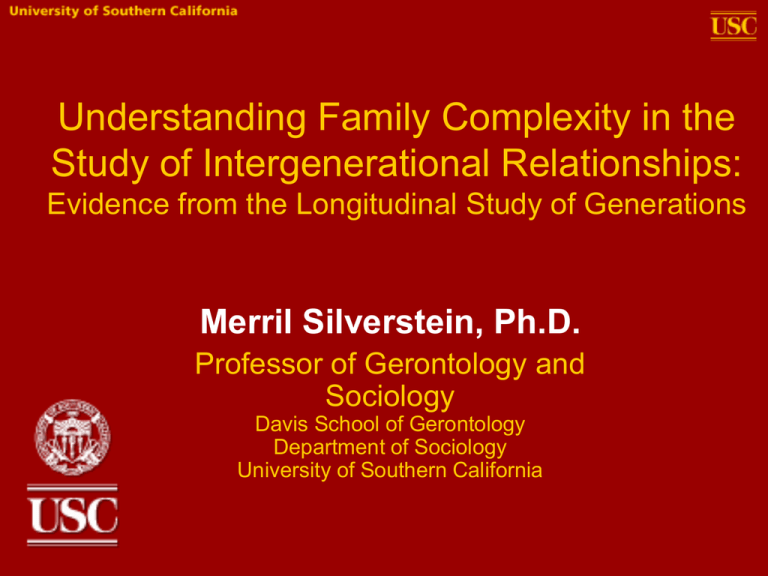

Understanding Family Complexity in the Study of Intergenerational Relationships: Evidence from the Longitudinal Study of Generations Merril Silverstein, Ph.D. Professor of Gerontology and Sociology Davis School of Gerontology Department of Sociology University of Southern California Families Through Historical Time • Increased longevity means greater co-survival between generations and prolonged relationships. • Possible kinship issues o Fertility decline o Higher prevalence of divorce, remarriage, step-families o Geographic distance increasing o Weaker sense of filial obligation • How to study social change in real time instead of using retrospective reports or using “proxy” evidence? • How to better approach families systemically? Studies of Families and Social Change • Using a single individual as informant about family process at one historical moment limits research questions that can be addressed • Use of retrospective reports has biases • Cross-sectional comparisons regarding social change of interest (e.g., divorced vs. married) ignores socio-historical context • Cohort studies in repeated cross-sections ignore intra-familial dependence and cannot address issues that require parent-child data Generational-Sequential Design • Members of different generations in the same families measured at the same age but at different historical periods to test for effects of social conditions at a common life-stage. • Useful for studying age-dependent processes where social conditions are also changing. 5 Comparison of Intergenerational Relations Across Historical Contexts • Historical/generational change in the quality of intergenerational relationships – Requires early reports from parents and later reports from children • Has the quality of older parent-child relations weakened over historical time? • If so, is this related to: – Increasing geographic distance – Rising divorce rates – Weakening norms of familism The USC Longitudinal Study of Generations (LSOG) • A multigenerational multi-time-point study, started in 1971 with repeated panels 2005. • Consists of about 3,000 individuals from 374 three-generation families recruited within Southern California region. • Full families are surveyed: grandparents, parents, and grandchildren (16+), including siblings, spouses, former spouses. • Fourth generation added in 1991 (Fifth generation in 2010). Design of LSOG Multi-generational Family Clusters Age and Period Design of LSOG 100 90 80 70 Age 60 G1 50 G2 G3 40 G4 30 20 10 0 1971 1985 1988 1991 1994 1997 Year of Meassurement 2000 2005 Age and Period Design of LSOG 100 90 80 70 Age 60 G1 50 G2 G3 40 G4 30 20 10 0 1971 1985 1988 1991 1994 1997 Year of Meassurement 2000 2005 Application of Generational Sequential Design • Do G3 children maintain less close relationship to their parents than G2 parents maintained with their parents? • Is so, does a G3-G2 difference persist after controlling for individual-level variables representing the “social change” of interest. • Methodological individualism: characteristics of serial generations proxy the social change of interest by virtue of their unique historical/cohort experiences. Sample & Design • Data for this analysis from LSOG: 554 G2s in 1971 and their G3 children surveyed between 1991 2005. – G2s averaged 44 years of age in 1971. – G3s reached the age of each parent somewhere between 1991-2005. For each G3 we use the survey that matches the closest to their parent’s 1971 age. • Use multilevel modeling to estimate change in emotional closeness to parents over time in G2s and G3s, comparing (1) slopes and (2) levels at the historical time when they match in age. Cross-Generational Comparisons in the LSOG T1 T2 T3 T4 T5 T6 T7 T8 Year 1971 1985 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2005 G2 43 57 60 63 66 59 72 77 G3 20 34 37 40 43 46 49 54 16 19 22 25 30 G4 Cross-Generational Comparisons in the LSOG T1 T2 T3 T4 T5 T6 T7 T8 Year 1971 1985 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2005 G2 43 57 60 63 66 59 72 77 G3 20 34 37 40 43 46 49 54 16 19 22 25 30 G4 Predicted for Emotional Closeness to Mothers in Two Linked Generations Centered on Age Match Emotional Closeness to Mothers 25 24 23 Cohort Gap 22 21 G2 Mothers 20 19 G3 Children 18 17 16 15 -33 -19 -16 -13 -10 Age -7 -4 0 14 17 20 23 Centered by Matched G2-G3 26 29 33 Predicted Emotional Closeness to Fathers in Two Linked Generations Centered on Age Match Emotional Closeness to Fathers 25 24 23 22 Cohort Gap 21 G2 Parents 20 19 G3 Children 18 17 16 15 -33 -19 -16 -13 -10 -7 -4 0 14 17 20 23 Age Centered by Matched G2-G3 26 29 33 Predicted Emotional Closeness to Mothers in Two Linked Generations Centered on Age by Health of G1 Mothers Emotional Closeness to Mothers 24 G2 Mothers: G1 Mothers NO IADL 22 20 G2 Mothers: G1 Mothers MOD IADL 18 16 G2 Mothers: G1 Mothers HIGH IADL 14 12 G3 Children 10 -33 -19 -16 -13 -10 -7 -4 0 14 17 20 23 Age Centered by Matched G3-G2 26 29 33 Multi-level Regression Results Predicting the G3-G2 Cohort Gap Average G3 - G2 Difference in Closeness to Parents When Generations are Age-Matched (40-50) G3-G2 Affection 0 -0.5 -1 * -1.5 * ** * ** * With Mothers With Fathers -2 Demographic Distance Added Divorce Added Norms of Controls Familism Added Cross Generational-Sequential • Transmission of values, attitudes, beliefs, behavioral tendencies across age-matched generations within the same families. • Multi-actor data? • Causal direction? • Research questions focusing on interdependencies and influence across family actors over time call for 20 unique approaches. • Religion is a family affair. • Children are socialized to religious traditions by parents and grandparents • Do grandparents influence the values, attitudes, and beliefs of their grandchildren beyond the influence of parents, synergistically with parents, and as mediated by parents? LSOG Data: Lagged Triads • Grandparents in 1971 (mean age =44) – G2 = 257 • Parents in 1988 (mean age = 40) – G3 = 341 • Grandchildren in 2005 (mean age = 31) – G4 = 565 Measures of Religiosity • Practice – Attendance at religious services: “never” to “everyday” • Salience – Importance of “a religious life” ranked among 13 social values • Identity – How religious are you?: “not at all” to “very religious” • Beliefs – Strength of conservative religious beliefs: agreement with statements • • • • God exists in the form as described in the Bible All people today are descendents of Adam and Eve All children should receive religious training Religion should play an important role in daily life • Additive scale (standardized factor score) computed for each generation Nesting of Grandchildren in Two Three-Generational Families: Basis for Multi-level Modeling Parent #1 Parent #1 Parent #2 Parent #2 Parent #3 Grandparent: Red Grandparent: Green Empirical Results from Multilevel Models Transmission of Religiosity .10* .32*** Grandparent Religiosity 1971 .38*** Parent Religiosity 1988 Grandchild Religiosity 2004 Effect on GC Religiosity 0.5 Standardized Effects of Parents' and Grandparents' Religiosity on Grandchildren's Religiosity 0.4 .38*** 0.3 0.2 .10* .12* 0.1 0 Parents' Direct Effect Grandparents' Direct Effect Grandparents' Indirect Effect • Parents’ direct influence is almost four times that of grandparents, but grandparents do directly influence their grandchildren net of parents. • Grandparents also indirectly influence their grandchildren through parents. Total influence of grandparents (.22) is 58% that of parents (.38). Source: Copen & Silverstein, 2007, Journal of Comparative Family Studies. Grandchildren's Religiosity by Levels of Grandparent's and Parent's Religiosity GC Religiosity 0.6 0.4 Lower Par Religiosity 0.2 0 Higher Par Religiosity -0.2 -0.4 -0.6 Lower GP Religiosity Higher GP Religiosity • Grandchildren are most religious when both their parents and grandparents are more religious. • Suggests that several generations together reinforce a family culture of religiosity. Grandchildren's Religiosity by Grantparent's Religiosity and Parental Marital History GC Religiosity 0.3 Intact Marriage 0.2 0.1 0 Ever Divorced -0.1 -0.2 -0.3 Lower GP Religiosity Higher GP Religiosity • Grandparents are better able to transmit their religiosity to grandchildren within intact families. • Parental divorce is associated with less religiosity in their children; grandparents do not compensate. Measures of Gender Role Attitude • Husbands ought to have the main say in family matters [Disagree] • Women’s liberation ideas make a lot of sense to me [Agree] • It goes against nature to put women in positions of authority over men [Disagree] • Women who want to remove the word “obey” from the marriage service don’t understand what it means to be a good wife. [Disagree] • Additive scale (standardized factor score) computed for each generation Empirical Results from Multilevel Models Transmission of Gender Role Attitudes .10* .11 Mother Contact with Grandmother 1988 Grandmother Gender Role Attitudes 1971 .09** .16** Mother Role Attitudes 1988 Grandchild Gender Role Attitudes 2005 Longitudinal Generational-Sequential Design in the LSOG Using 14 Years Historical Period 1971 ---------->1985 Life Stage Transition Age Span (Gen) Early Adulthood 19 -------> 33 (G3) Middle Adulthood 44 -------> 58 (G2) Late Adulthood 64 -------> 77 (G1) Historical Period 1991 ---------->2005 Age Span (Gen) 19 -------> 31 (G4) 42 -------> 56 (G3) 63 -------> 76 (G2) 31 Summary • Generational-sequential designs provide useful tools for understanding how societal change is manifest in micro-family environments and across multiple family members. • Generational differences can be investigated with GSD in terms of change across cohorts – Intergenerational ties weakening over historical time. • And in terms of cross-cohort continuity – Intergenerational transmission occurring (and possibly changing) over historical time.