When Military Youth Relocate

advertisement

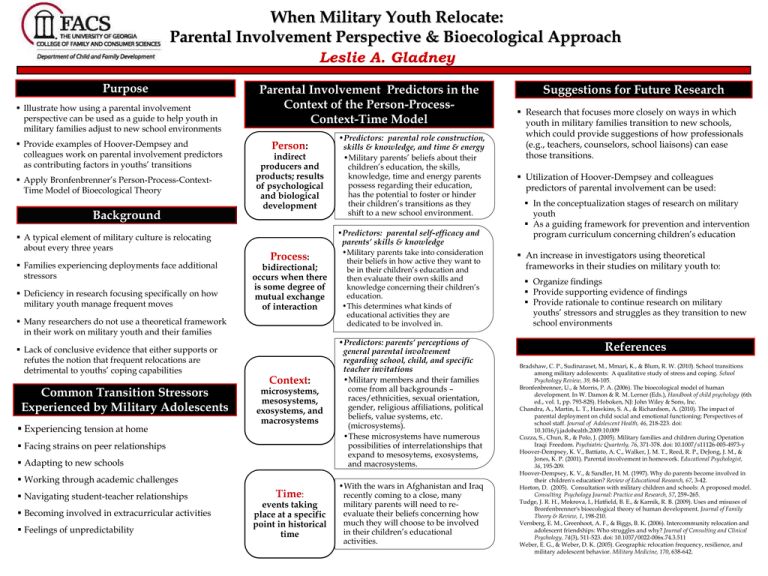

When Military Youth Relocate: A Parental Involvement Perspective & Bioecological Approach Leslie A. Gladney Purpose Illustrate how using a parental involvement perspective can be used as a guide to help youth in military families adjust to new school environments Provide examples of Hoover-Dempsey and colleagues work on parental involvement predictors as contributing factors in youths’ transitions Apply Bronfenbrenner’s Person-Process-ContextTime Model of Bioecological Theory Background A typical element of military culture is relocating about every three years Families experiencing deployments face additional stressors Deficiency in research focusing specifically on how military youth manage frequent moves Parental Involvement Predictors in the Context of the Person-ProcessContext-Time Model Person: indirect producers and products; results of psychological and biological development Process: bidirectional; occurs when there is some degree of mutual exchange of interaction Many researchers do not use a theoretical framework in their work on military youth and their families Lack of conclusive evidence that either supports or refutes the notion that frequent relocations are detrimental to youths’ coping capabilities Common Transition Stressors Experienced by Military Adolescents Experiencing tension at home Context: microsystems, mesosystems, exosystems, and macrosystems Facing strains on peer relationships Adapting to new schools Working through academic challenges Navigating student-teacher relationships Becoming involved in extracurricular activities Feelings of unpredictability Time: events taking place at a specific point in historical time •Predictors: parental role construction, skills & knowledge, and time & energy •Military parents’ beliefs about their children’s education, the skills, knowledge, time and energy parents possess regarding their education, has the potential to foster or hinder their children’s transitions as they shift to a new school environment. •Predictors: parental self-efficacy and parents’ skills & knowledge •Military parents take into consideration their beliefs in how active they want to be in their children’s education and then evaluate their own skills and knowledge concerning their children’s education. •This determines what kinds of educational activities they are dedicated to be involved in. •Predictors: parents’ perceptions of general parental involvement regarding school, child, and specific teacher invitations •Military members and their families come from all backgrounds – races/ethnicities, sexual orientation, gender, religious affiliations, political beliefs, value systems, etc. (microsystems). •These microsystems have numerous possibilities of interrelationships that expand to mesosytems, exosystems, and macrosystems. •With the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq recently coming to a close, many military parents will need to reevaluate their beliefs concerning how much they will choose to be involved in their children’s educational activities. Suggestions for Future Research Research that focuses more closely on ways in which youth in military families transition to new schools, which could provide suggestions of how professionals (e.g., teachers, counselors, school liaisons) can ease those transitions. Utilization of Hoover-Dempsey and colleagues predictors of parental involvement can be used: In the conceptualization stages of research on military youth As a guiding framework for prevention and intervention program curriculum concerning children’s education An increase in investigators using theoretical frameworks in their studies on military youth to: Organize findings Provide supporting evidence of findings Provide rationale to continue research on military youths’ stressors and struggles as they transition to new school environments References Bradshaw, C. P., Sudinaraset, M., Mmari, K., & Blum, R. W. (2010). School transitions among military adolescents: A qualitative study of stress and coping. School Psychology Review, 39, 84-105. Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (6th ed., vol. 1, pp. 793-828). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Chandra, A., Martin, L. T., Hawkins, S. A., & Richardson, A. (2010). The impact of parental deployment on child social and emotional functioning: Perspectives of school staff. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46, 218-223. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.10.009 Cozza, S., Chun, R., & Polo, J. (2005). Military families and children during Operation Iraqi Freedom. Psychiatric Quarterly, 76, 371-378. doi: 10.1007/s11126-005-4973-y Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Battiato, A. C., Walker, J. M. T., Reed, R. P., DeJong, J. M., & Jones, K. P. (2001). Parental involvement in homework. Educational Psychologist, 36, 195-209. Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., & Sandler, H. M. (1997). Why do parents become involved in their children's education? Review of Educational Research, 67, 3-42. Horton, D. (2005). Consultation with military children and schools: A proposed model. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 57, 259–265. Tudge, J. R. H., Mokrova, I., Hatfield, B. E., & Karnik, R. B. (2009). Uses and misuses of Bronfenbrenner's bioecological theory of human development. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 1, 198-210. Vernberg, E. M., Greenhoot, A. F., & Biggs, B. K. (2006). Intercommunity relocation and adolescent friendships: Who struggles and why? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(3), 511-523. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.74.3.511 Weber, E. G., & Weber, D. K. (2005). Geographic relocation frequency, resilience, and military adolescent behavior. Military Medicine, 170, 638-642.