Slumclearance-outline

advertisement

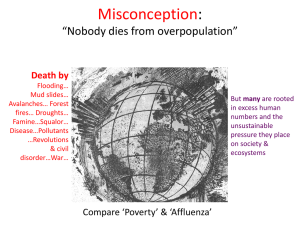

I think that the core theme I want to address will have something to do with the notion of what problems slum clearance has been seen to be supposed to solve, what problems it has actually been meant to solve, and what problems it has created – or something like that. Purportedly meant to help provide decent housing for all households In UK, owner-occupation has been seen as the primary way of accomplishing this In 30s slum clearance did help successfully rehouse a lot – in houses in burbs, mostly In 50s-60s, SC and urban rehousing often failed to provide better Often succeeded, but failures were so spectacular that severely damaged reputation of public housing Summary: some major successes, particularly early on. Some flamboyant failures. Slum clearance a very powerful policy tool. Ultimately, its biggest policy impact may have been to help fatally weaken the reputation of public housing. There has always been a housing problem In 19th c, SC evolved not to address housing problems per se, but to address broader issues of public health Industrialisation had brought great wealth and great squalor Slums seen to cause public health crisis Clearing them helped reduce Tension: property rights v public good Slums were a nuisance. Nuisance removal act: unfit for human habitation (M 27) First housing acts were not meant to solve housing problems In fact, created many. We will see that creating problems was not unique to housing policy of the day. “The cheapest remedies… are those of prevention. An ill-planned town can never have all the errors of its first formation corrected.” (in M 29) By end of 19th c, the slums were seen as a housing problem: the poor lived in unsuitable housing and something must be done. This something was to knock down slums and build better. Housing of the Working Classes Act 1890 first ties slum clearance with building. But no obligation – and about general needs, not poorest Filtering up M (36) says that “before 1914 there was barely a recognisable housing policy as such”. Slum clearance in UK inextricably tied to development of public housing. But what kind of public housing? Slum clearance doesn’t happen after wars. Modern slum clearance kicked off with Greenwood Act of 1930 (Power 1993: 182) For first time councils had responsibility to rehouse entire communities Lots of stats in ibid. Eg, about four m people were forcibly moved from slums in the 30s, more than any other decade. Also “one m council houses were built under the 1930s slum clearance programme.” The key issue is who they were built for. Council houses in the 20s had been built for better-off working class. Malpass says this was govt solving a political problem rather than a housing one. (12) It was a response to voice. (Later, CH will be for people who lack voice, and will add to or at least continue this problem.) Beginning in 1930, central govt made a conscious decision: public housing was to be for the least well-off. (Later I’ll discuss why.) Slum clearance was to be a key tool in solving the problem of housing the least well-off. By the start of WWII, pattern set. CH for the least well-off, private market for rest. In the natl psyche, writes M, CH had become firmly embedded as the tenure that catered for slum dwellers. “But it provided mainly suburban houses and it was vastly better than run-down slums” (183). (So it was a good brand in many ways.) Here add quote from Kinship book. This reputation would prove very fragile indeed. Following WWII, Bevan refuses to push for super-high numbers. Quote Note that when numbers do rise under Macmillan, it’s because private numbers do. In 1950s, SC again enters national centre stage re policy, as in Victorian public health scare days. Helps propel Mac to leadership Again, when private industry handles better-off wc, slum clearance becomes a tool for providing cheap homes (people’s houses) for the worst off. Slum clearance rebuilding is complementary to private market Tabula rasa Public housing becomes ever more for worst off Slum clearance blights cities Property put before people Builders are having a laugh When policy is aimed at a group that lacks political power, it doesn’t have to go through checks and balances. It can become a F’s monster. “All we needed was some toilets.” New Jerusalem becomes New Canaan. In the end, the monster turned on itself: Ronan Point, corruption scandals. Small is beautiful movement. A conclusion.

![4d2 Nutta`s presentation RNS[1]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005527547_1-de4e3c0b9321c155137e6e0411d9c94f-300x300.png)