Pompeii and Herculaneum

Shops and businesses

It is important to study shops and businesses because it gives us an insight into the daily life of Ancient Romans; what they ate, bought, their likes and dislikes, and most importantly how they behaved.

In this lesson we will look at a number of examples from Pompeii and one from

Herculaneum (only because it is covered in volcanic rock!).

Pistrinum – bakery

Fullonica – laundry

Officina Coriariorum – tannery

Garum production – fish sauce

Lupanar – brothel

Thermopolium – cafe/bar

Bread was a staple food item throughout the

Roman Empire; so it is of little surprise that archaeologists have uncovered bakeries at both

Pompeii and Herculaneum.

In most establishments the equipment for the production of bread consisted millstones made from porous lava, a very hard wearing stone that wouldn't lose fragments and spoil the flour produced.

After baking, the bread, which came in several different varieties, was then generally sold on in an adjoining shop, although this was not always necessarily so:

At times was distributed to sellers or shops.

Pompeii Herculaneum

The Fullonica was the ancient Roman version of the laundromat. There were several laundries in Pompeii of which the Fellonica of Stephanus is a great example.

Fellonica of Stephanus was formally a private house but was renovated into a laundry business.

Clothes were cleaned using human urine and clay; it was finally rinsed, dried and pressed.

b a c d e g h f i j a. Entrance (vestibule) b. Office c. Main Hall (atrium) d. Service room e. Living room (oecus) f.

Dining room (tricilinium) g. Master bedroom (tablinum) h. Open courtyard (peristyle) i.

Kitchen j.

Rinsing pools

f a e b c i j h

Notorious for its unpleasant smell, the tannery, or officina

coriariorum, was also part of urban life.

Process of preparing skins:

Skins typically arrived at the tannery dried stiff and dirty with soil and gore.

The tanners would soak the skins in water to clean and soften them.

They would then pound and scour the skin to remove any remaining flesh and fat.

Next, the tanner would loosen the hair fibres by soaking the skin in urine, before scraping them off with a knife.

Once the hair was gone, the tanners would remove the outer protein layer by pounding dung into the skin or soaking the skin in a solution of animal brains.

It was this combination of urine, animal faeces and decaying flesh that made ancient tanneries so malodorous.

Owning a tannery was not without its rewards though (see mosaic to the right)

The skull is crowned with a carpenter's square and plumb-bob, which dangles before its empty eyesockets (death as the great leveller), while below is an image of the ephemeral and changeable nature of life: a butterfly (the soul) atop a wheel (fortune). On each side, kept in balance by death, are the symbols of wealth and power on the left (the sceptre and purple) and poverty on the right (beggar’s scrip and stick).

This is quite an intricate piece of work and would have been expensive to purchase. It suggests that being a

Tanner would have been quite a well paid and respected profession.

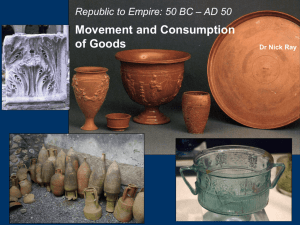

The Garum Workshop was concerned with the distribution rather than the production of garum, a fish sauce which was a staple of

Roman cuisine and could be used as a condiment with almost anything.

Garum was made by the crushing and fermentation in brine of the intestines of fish such as eel, tuna, anchovies and mackerel. The sauce was stored in bulk in the workshop and decanted into smaller vessels for sale.

The production of garum must have been carried out at Pompeii as Pliny notes that the city was renowned for its garum:

“no other liquid except unguents has come to be more highly valued.”

Garum production created an unpleasant smell, its fermentation was relegated to the outskirts of cities as must have been the case with Pompeii as no evidence of its production has been found within the city walls.

Storage of garum (see above)

Sold in containers (see above)

The ‘Lupanar’ is one of well over thirty possible 'houses' of prostitution known in

Pompeii, although it is believed to be the only one purpose built for such use.

The lupanar had ten rooms, five on the ground floor and five larger ones on the upper floor accessed by a wooden staircase

(see photograph on next page). The rooms had built in masonry beds onto which mattresses were placed.

Erotic scenes were painted above each door and the walls bore a large number of inscriptions (over 120) scratched by the clients and the working girls.

The prices were very low, one of the reasons being that these brothels were frequented by the lower levels of society and by slaves. On average the cost of a sexual service was two asses, the equivalent of the cost of a loaf of bread.

A thermopolium was the equivalent of a modern day cafe/bar. Hot and cold food was sold from what was usually an 'L' shaped masonry counter containing terracotta vessels.

There are more than 160 thermopolia in

Pompeii, of which almost half have marble surfaced counters.

They had complex socio-economic foundations in their towns and cities.

The success of the Empire rested on agriculture, production and distribution of goods, and trade.

The economy of Pompeii and Herculaneum was primarily agricultural with a smaller number of trade and crafts practiced. The production of bread, garum, wine and olive oil were primary industries.

Pompeii is an important centre for the:

sale of textiles, fabrics and clothing

production of goods and trade

Skills and training were paramount in maintaining successful communities.

There is a shift from personal production of goods to a reliance on purchasing goods from shops and factories.

The distribution of wealth is evident – many shops and businesses.

Pompeii and Herculaneum are wealthy towns due to foreign trade and location.

Emphasis placed on a comfortable city life – taverns, brothels, cafes.