Female Offenders

Perceptions’ of Prison

Dr Isla Masson & Dr Serena Wright

ab7919@coventry.ac.uk & sw639@cam.ac.uk

Introduction to the different

research projects

Two ends of the same scale for our doctoral research:

IM - Women serving a first short sentence

SW - Women classified as prolific or persistent offenders

The unheard voices of women

Both wanted to explore the lives of a minority within

our criminal justice system – did this through different

interview techniques:

repeat, semi-structured vs. in-depth, life history

Inability Of Short Sentences To

Address Needs [i]

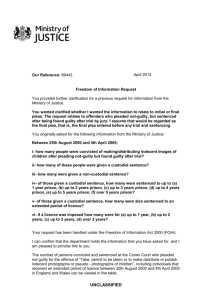

Last year 8/10 sentenced female prison receptions were

serving under 12 months, the majority of which were serving 6

months or less (Ministry of Justice, 2014)

“I did pottery but I only just started it, I didn’t get a certificate

because of the short period of time. They said it would take

about six weeks...If I had more time I would have achieved so

much more” (Debbie, 27, sentenced, 2months Breach of an

order).

“I think is the big thing that needs to change in the system is

that…there’s not a lot of support set up for people doin’ short

sentences in the prison?…Um, you’re basically just in limbo – you

get pushed to the side…and there’s not a lot of courses there for

people that are doing short sentences, or even release plans for

them” (Amy, 31, sentenced, 3 years Robbery).

Inability Of Short Sentences To

Address Needs [ii]

• Short sentences failure to address range of ‘needs’, means

that longer sentences could – counter-intuitively - seem

preferable

“But part of me [slaps her leg – sounds almost angry with herself]

wants tae come back’ – isn’t that sad…It maybe sounds harsh but

I’m gonna ask the judge, I’ll say ‘Please can you give me some

more time in this prison’”(Lennox, 62, remanded, Breach of

ASBO).

“I said to them I’d prefer to remain in prison, they said ‘no they

can’t leave me in the prison I have to go’… ‘When I’m out how can

I cope?’ I said. ‘Let me stay here until you people make a

decision’” (Steph, 30, sentenced, 8months Theft).

A traumatic event vs.

A place of safety and change [i]

“The first couple of weeks I could understand why people would

want to kill themselves...When they first shut the door I thought

I can’t do the next four months behind these bars and being

searched and it was degrading, and I’ve never been in trouble in

my life...I didn’t stop crying...I couldn’t eat, I’d stick it straight

in the bin” (Marie, 42, sentenced, 8months Theft).

“There was times when I thought I wasn’t going to get out of

there alive, because it was you know women fighting, girls

cutting themselves with razor blades...in there you can’t see

the light at the end of the tunnel, you think you’re not coming

out” (Bella, 40, sentenced, 3months Non-payment of council

tax).

A traumatic event vs.

A place of safety and change [ii]

‘[A]lthough prison is hardly a preferable environment in which to

do so, the people, vocational & educational opportunities,

meaningful work, & counselling available…can empower and

encourage her in that long, hard struggle’ (Clark, 1995: 324).

“You’re wrapped up in a prison environment, it’s safe – I know that

sounds mad but it is; if you’re off the streets it’s safe, and then you

step out there and it’s chaos – for somebody like me, it’s chaos”

(Morgan, 31, 3years 6months Intent to Supply Class A).

“Here I can achieve something with my life. I’m happy here, I can go

to education, I can make plans…I know it sounds strange, but in a

way I want to stay in prison and get on with my education” (Debbie,

27, sentenced, 2months Breach of an order).

Post-prison: Problems securing

accommodation

Accommodation ‘is women’s greatest resettlement concern on

release and it seems to me to be the pathway most in need of

speedy, fundamental gender specific reform’ (Corston, 2007:

8).

“I did think prison was going to help me, everybody in there was

like ‘don’t worry about it, you’ll get housing, you’ll get

housing’. You don’t, you’ve got to be in there for 12 months

minimum before they will give you housing” (Donna, 33,

sentenced, 6months Theft).

“I got out to nothing again, um, my mum didn’t wanna know,

didn’t have nowhere to live, didn’t have no one to get out to so

went back to the same routine [drug use, and selling sex to fund

it]” (Louise, 23, sentenced, 2years 4months Burglary).

Post-prison: Problems securing

appropriate accommodation

“There’s no point in me doing a detox [in prison] and

then throwing me back in a fucking junkie-filled hostel”

(Badger, 26, sentenced, 4years 6months Burglary).

“The place wasn’t conducive for my baby...no matter

how much you clean, there was rats because the

dumpster is not far away, so there’s always rats coming

from gardens into your home, into your toilet holes...so I

had to take them to court to move me” (Bryony, 32,

remanded, False passport).

Concluding Thoughts

Some experiences seemed positive, however this was

relative to their chaotic lives outside

For some, being released was more stressful,

particularly in regards to accommodation, which was

often less than appropriate

Lessons are not being learned or what has been learned

is not being acted upon in a sustained manner

(Heidensohn (1998), Gelsthorpe (2006), and Player

(2013))

Reference List

Clark, J. (1995) The Impact of the Prison Environment on

Mothers. The Prison Journal 75(3): 306-329.

Corston, J. (2007) The Corston Report: A Review of Women

with Particular Vulnerabilities in the Criminal Justice

System. London.

Gelsthorpe, L. (2006) COUNTERBLAST. Women and criminal

justice: Saying it again, again, and again. The Howard

Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4): 421-424.

Heidensohn, F. (1998) Translations and refutations: An

analysis of changing perspectives in criminology. In S.

Holdaway and P. Rock [Eds]. Thinking about criminology

(pp.40-53). London, UK: UCL Press.

Reference List

Masson, I. (2014) The Long-Term Impact of Short Periods of

Imprisonment on Mothers. PhD Thesis, King’s College London.

Ministry of Justice. (2014) Annual tables - Offender

management caseload statistics 2013 tables: Female receptions

into prison establishments by type of custody, sentence length

and age group, 2003-2013. London: MoJ.

Player, E. (2013) Women in the criminal justice system: The

Triumph of Inertia. Criminology and Criminal Justice, 0(0):1–

22.

Wright, S. (2014) ‘Persistent’ and ‘prolific’ offending across

the life-course as experienced by women: Chronic recidivism

and frustrated desistance. PhD Thesis, University of Surrey.