Chapter 8 - Amazon Web Services

advertisement

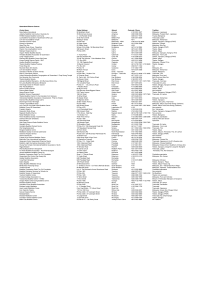

Main topics covered • Introduction • Practical religion in Indian Buddhism • Practical religion in Tibet • Lamas, monks and monasteries as fields of karma • Death rituals – ‘Tibetan Book of the Dead’ • Maintenance of good relations with local gods and spirits; protection against malevolent spirits • Rituals for prosperity, success and good fortune • Rituals for health and long life • Divination and diagnosis • Tibetan ritual: pragmatic, karma-oriented and Bodhic dimensions Key points 1 • A central issue for Tibetan Buddhists is the ritual management of Tantric power to protect the community and to maintain the health and prosperity of its members. This practical focus is something that Tibetan Buddhism shares with most pre-modern religions, and Tibetan Buddhism has retained it more than many other Buddhist traditions that have been more influenced by European, and specifically Protestant Christian, notions of religion. • Historically, too, Tibetan Buddhism, with its heritage from Tantric Buddhism in India, has been more concerned with questions of everyday life than Buddhism in countries such as Sri Lanka or Thailand, where these were mostly the domain of parallel religious cults of this-worldly spirits and deities carried out by lay priests. Key points 2 • As in other Buddhist countries, making offerings to Buddhist clergy (which in Tibet includes lamas as well as monks and nuns) is a primary way for lay people to gain merit or ‘good karma’ that will have positive effects in future lives. Lay people also regularly seek the assistance of Buddhist clergy at the time of death and for funerary rituals. Practices for guiding the consciousness of the dying person, including among others the rituals related to the so-called ‘Tibetan Book of the Dead’ are of considerable importance. Price list for ritual services Cost (in Indian rupees) for different ritual services, Nyingmapa monastery, Rewalsar, India, photo 1989 Key points 3 • Buddhist clergy are also primarily responsible for maintaining good relationships with the local spirits and deities. The role of clergy here differs from that of lay people; lay people make offerings to local gods and seek their protection, while lamas are expected to control the local gods and ensure their obedience through Buddhist Tantric power. Their ability to do this goes back to the original ‘taming’ of the local gods by Guru Padmasambhava. • As with other Tibetan Buddhist rituals, however, these processes of ‘taming’ can be understood at a number of levels (usually classified as ‘outer’, ‘inner’ and ‘secret’). Chorten and the landscape Three chorten (stūpas) at the river confluence at Chudzom, Bhutan, photo 2009 Key points 4 • Lay shamanic specialists, such as the lhawa or spirit-mediums, provide a channel for communication with local deities, and also perform some ritual services, including the recovery of lost soul or spirit-essence (la). These specialists are generally trained under the supervision of lamas and are thought of as subject to their authority. Sang offering to local gods Sang offering to local deities, Yarlung Valley, Central Tibet, 1987 Sang offering, Jokang, Lhasa Sang offering in front of Jokang, Lhasa, 1987 Sang offerings Sang offering substances for sale near Jokang, Lhasa, 1987 Key points 5 • Monastic festivals, including ritual dances (cham) and long-life empowerments (tsewang) are an important occasion for demonstrating and representing the ongoing exchanges between community and clergy. These and other rituals are concerned with the defence of the community against supernatural harm and the maintenance of the health, welfare and prosperity of its members. Long-life rituals include a more sophisticated version of the recovery of lost soul or spirit-essence (la) that is also performed by lay specialists. Monastic dances (Cham) Cham ritual dance, Namdrolling, Bylakuppe, South India. Photo by Ruth Rickard, 1991 Long-life deities Three Long-Life Deities (Uṣṇiṣavijāy, Amitāyus, White Tārā). Gangteng Monastery, Pobjika, Bhutan, photo 2009 Key points 6 • Divination is a major concern of Tibetan Buddhists and can be carried out by lamas as well as by lay diviners. It is concerned not so much with prediction as with deciding the best course of action in a particular situation. Lay diviner Ama Anga, a lay diviner in Dalhousie. Photos by Linda Connor, 1996 Gesar arrow divination Namka Drimé Rinpoché performing Gesar arrow divination, photo 1990 Key points 7 • Tibetan Buddhist practices can be thought of as concerned with a variety of levels or spheres: pragmatic (this-worldly), karmaorientated (concerned with future lives), and Bodhic (concerned with the attainment of Buddhahood). All of these are important to Tibetans, and Tibetan religious practices can often be understood and practised at more than one, or all three, of these levels.