Speech Perception Lecture

advertisement

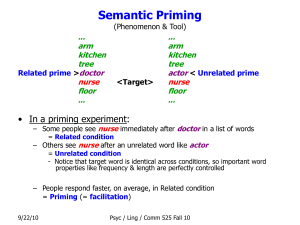

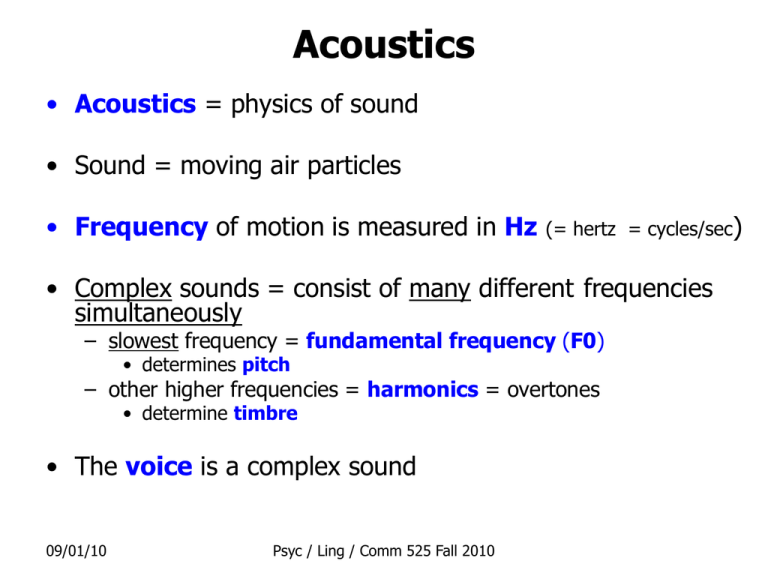

Acoustics • Acoustics = physics of sound • Sound = moving air particles • Frequency of motion is measured in Hz (= hertz = cycles/sec) • Complex sounds = consist of many different frequencies simultaneously – slowest frequency = fundamental frequency (F0) • determines pitch – other higher frequencies = harmonics = overtones • determine timbre • The voice is a complex sound 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Some Different Ways to Depict Sound 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Acoustics of Speech • Fundamental Frequency (F0) – basic pitch of voice – rate at which whole vocal cords vibrate • Plus harmonics (= overtones) – other higher frequencies in voice – faster rates at which parts of vocal cords & other structures vibrate • Resonance (= sympathetic vibration) – rest of vocal tract enhances some frequencies & inhibits others – freqs that are enhanced or inhibited depends on vocal tract shape – which depends on positions of articulators – Produces formants • enhanced frequency bands • usually 3-4 formants in speech: F1, F2, & F3 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Speech & Hearing Frequencies • Human hearing – 20 - 20,000 Hz – Most sensitive at 500 - 5,000 Hz • Human voice fundamental frequency – Average for men – Average for women = 80 - 200 Hz = up to 400 Hz • Telephone: – Cuts off at ~3000 Hz – Crucial information for identifying some sounds lost (fricatives) 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 From Carroll (2004), The psychology of language, 4th Ed. 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 English Spelling A Dreadful Language I take it you already know Of tough and bough and cough and dough. Others may stumble, but not you, On hiccough, thorough, touch, and through; Well done! And now you wish perhaps To learn of less familiar traps? Beware of heard, a dreadful word That looks like beard and sounds like bird. And dead: it's said like bed, not bead For goodness sake, don't call it "deed". Watch out for meat and great and threat (They rhyme with suite and straight and debt). A moth is not a moth in mother, Nor both in bother, nor broth in brother. And here is not a match for there, Nor dear and fear for bear and pear. And then there's dose and rose and lose Just look them up - and goose and choose, And cork and work and word and sword, And do and go and thwart and cart. Come, come I've hardly made a start. A dreadful language? Man alive I mastered it when I was five! 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) • 1 sound = 1 symbol • Symbols for all speech sounds in all languages • Phonetic writing makes pronunciation completely unambiguous – Some languages have writing systems that are close to phonetic (Korean, Italian) – Some other languages have writing systems that indicate less about pronunciation (Mandarin?) 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 (“Standard” American) From Carroll (2004), The psychology of language, 4th Ed. 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 From Carroll (2004), The psychology of language, 4th Ed. 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Coarticulation • Each sound partially shaped by sounds before & after it – keel vs kill vs cool – / kil / vs / kIl / vs / kul / (IPA characters) – place of articulation and rounding on the k differ a lot – so, different versions of “the same sound” in different contexts – and from different speakers • This is what allows us to talk so fast 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Coarticulation Across Languages • How different can different versions of a sound be & still be heard as “the same sound”? – Different for different languages – A back rounded k and a front unrounded k sound like “the same sound” to English speakers • but that same difference is enough to make them sound like 2 different sounds in some other languages 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Phonemes • In English, a difference in voicing makes 2 sounds “different sounds” – – pill /pIl/ vs vs bill /bIl/ – p = voiceless – b = voiced • Can find many other minimal pairs of English words where the only difference is whether or not one sound is voiced – – – – – rip bat tip cap back rib bad dip cab bag • Therefore, voicing is a distinctive feature in English – and 2 sounds that differ only in voicing are different phonemes – phoneme = sound that can signal a meaning difference 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Phonemes vs Allophones • There’s another difference between pill and bill in English – The p in pill is aspirated, but the b in bill is not • /phIl/ vs /bIl/ • aspiration = air puff when stop consonant is released • But, there are no minimal pairs of English words that differ only in whether or not one sound is aspirated – So, aspiration is a non-distinctive feature in English – 2 sounds that differ only in aspiration are allophones of the same phoneme – allophones = different versions of the “same sound” • But in Korean, it’s the opposite of English – aspiration is phonemic – voicing is allophonic 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Another Cross-Linguistic Example • In English, there is a minimal pair rip and lip – & many other pairs that differ in just r vs l – so r and l are different phonemes in English • In Japanese, there are no minimal pairs that differ only in r vs l – Instead, there’s a single phoneme that’s somewhere between the English r and l – and it has different pronunciations in different contexts • sometimes it sounds more like English r • and sometimes like English l • r and l are both allophones of a single phoneme • Makes it very difficult for Japanese speakers to hear the difference in English – Japanese speakers have learned to categorize all the allophones as “the same sound” 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Distinctive Features Across Languages • There are many kinds of differences between speech sounds – Some are important (= distinctive) & some are not – Which is which varies across languages • So, have to learn which are the important ones for your language • For English consonants, the distinctive features are: – Voicing (Voice Onset Time) – Place of articulation – Manner of articulation 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Speech Perception is Hard! • Coarticulation – allows us to talk fast – which leads to lack of invariance in acoustic signal 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Variability in Vowel Production From Kuhl, et al. (2004), Nat Rev Neurosci 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Speech Perception is Hard! • Coarticulation – allows us to talk fast – which leads to lack of invariance – a series of musical notes changing as fast as speech sounds do would sound like a blur – we would not be able to perceive individual notes – yet we have the impression that we hear each speech sound • This has led some researchers to propose that: – speech perception requires a hard-wired uniquely human ability that evolved specifically for speech • What sort of evidence would support this idea? 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Evidence about special status of speech perception • Categorical Perception – Inability to hear differences between members of a category – where category = phoneme – e.g., variants of /p/ with different VOTs – Together with ability to hear differences of the same size when the 2 sounds are members of different categories – e.g., /p/ vs /b/ • Adults can easily hear only the differences that are important in their language – e.g., English speakers easily hear difference between /r/ & /l/ • i.e., they sound like "different sounds“ – while Japanese speakers find it very hard to hear same diff • i.e., they sound like "the same sound" 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Categorical Perception • Categorical perception is strongest for voicing & place of articulation for consonants – Weaker effect for vowels called a “magnet effect” • Adults show categorical perception for the differences that are distinctive in their language – So, it depends on learning – How early is it learned? 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 From Carroll (2004), The psychology of language, 4th Ed. 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 From Carroll (2004), The psychology of language, 4th Ed. 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 From Carroll (2004), The psychology of language, 4th Ed. 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Testing Infant Speech Perception • Use a habituation paradigm to test perception – Infants suck on a pacifier with a transducer in it – Measure how hard & how often they suck – Whenever something interesting happens, they suck more • Play synthetic speech syllables that vary on some feature – e.g., VOT – Keep playing same syllable over & over until they're bored with it and their sucking rate decreases (= habituation) – Then change the syllable – If sucking rate goes up, they must have heard the change – If rate does not go up, either they couldn't hear the change, or it wasn’t interesting enough 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Categorical Perception in Infants • For VOT – Play a clear pa over and over – If then change to one with a different VOT, but that adults would call ba • English-hearing infants will speed up sucking rate • Therefore, they hear the difference – If instead change to one with a VOT that’s just as different from the first one, but it’s one adults would still call pa • Infants don’t speed up • Therefore, they didn’t hear the change (or it’s not interesting) • Suggests infants cannot discriminate between different versions of pa, but can discriminate between pa and ba – Just like English-speaking adults – So, English-hearing infants already have categorical perception 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 From Eimas et al. (1971), Science 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Infant Speech Perception Across Languages • Infants easily hear many differences that adults don’t – they start out able to hear differences that are not important in the language spoken around them • Japanese-hearing infants start out being able to hear the difference between r and l just as well as English-hearing infants • but by ~1 year old, they no longer hear that difference • All children start out able to hear (most of) the differences that are important in any human language – But over their 1st year, they lose the ability to hear differences that are not important in the language they’re hearing – the speech perception system gets tuned to hear only the differences that are important for the language being learned • Why by 1 year? • Maybe because that’s when they start to say words? (Werker) 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Video segment from PBS series The Mind (1989) 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Are there limits to the differences infants can hear? • Yes: Lasky et al. (1975) – Voicing is distinctive for stop consonants in English, Spanish, & Thai – But the boundary between voiced & voiceless is at different VOT values Thai Spanish English ------------------------------------------------------------------------60 -40 -20 0 +20 +40 +60 VOT (msec) • The Thai & English boundary values are common to many languages • The Spanish one is unusual – Spanish-hearing infants less than 1 year old • hear the difference between pairs of sounds that straddle both the Thai & English category boundaries • but not ones that straddle the Spanish boundary • So, infants hear most, but not all, differences used in any language 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Categorical Perception, cont’d • The same synthesized stimuli can be perceived as speech or not – Play formant transition to one ear (sounds like a chirp) – and steady-state part to other ear (sounds like vowel) • If tell people it’s speech, they integrate 2 ears & hear it as speech – but if don't tell them, they don't hear it as sounding like speech • When they do hear it as speech, get categorical perception – but not when they don’t hear it as speech • CP effects much stronger for consonants than for vowels • What seems to be critical is: – a short rapidly changing sound (e.g., consonant) – followed by a longer slower-changing sound (e.g., vowel) – where both heard as part of a single input 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Is categorical perception unique to humans? (i.e., Is it evidence that speech perception is special?) • No – Many other animals show results like human infants in habituation paradigms – They can discriminate between sounds that humans would call different phonemes – and cannot discriminate between sounds that humans would call the same phoneme • So, human speech takes advantage of properties of auditory system – by generally using the differences that are easy to hear to signal important contrasts in the language 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 What GOOD is categorical perception??? • Categorical Perception = a failure to discriminate speech sounds any better than you can identify them • How can it be desirable to lose the ability to hear differences??? – Speech is hugely variable • • • • coarticulation different speech rates different speakers with different voices & accents ... • - The auditory system learns to attend to the differences that are important and to ignore the ones that are not • - Lets us tune out a lot of irrelevant variability • - Can adults re-learn to hear differences they’ve learned to ignore? - Yes, but it requires a particular kind of training 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 McGurk Effect Visual cues in speech perception • Conflicting acoustic and visual cues can lead to blended perception of sound – If there’s a sound in the language that’s • close enough to the acoustic signal • & fits with the visual cues 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 More on Visual Context Effects (Gilbert, Lansing, & Garnsey, in prep) • Participants heard either /ba/ or /ga/ (50-50) • Task = Did you hear /ba/? (50-50) • Syllables embedded in several levels of noise as well as in quiet • Simultaneous visual cue – – – – 09/01/10 Static rectangle Static smiling face Chewing face (irrelevant motion) Speaking face (relevant motion) Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Accuracy d' Senstivity 3.5 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 Quiet 0 dB SNR -9 dB SNR 1.0 0.5 0.0 -18 dB SNR Rect AR Smile ASF Chew ADF Speak AV Visual Cue Type Presntation Condition VO - Informative facial motion completely compensates for noise - Other facial cues have no effect on accuracy 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Event-Related Brain Potentials (ERPs) N100 component Speak Chew - Earlier & smaller when speech easy to identify - Irrelevant face motion speeds up N100 just as much as relevant motion - But doesn’t reduce its amplitude N100 - Maybe potentially relevant face motion serves an alerting function? 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010 Smile Phoneme Restoration • Replace one phoneme in an utterance with noise – If the phoneme is predictable from context, people “hear” the missing sound (e.g., legi*lature) – If tell them a sound has been replaced, they’re not accurate at identifying which sound it is – Warren & Warren (1970) • Stimuli (acoustically identical except for last word) – – – – It was found that the *eel It was found that the *eel It was found that the *eel It was found that the *eel was on the orange. was on the axle. was on the shoe. was on the table. • People believed they had heard the phoneme that made sense given the final word – Final word can’t have influenced what they heard at *eel 09/01/10 Psyc / Ling / Comm 525 Fall 2010