48x36 Poster Template - Utah State University

Introduction

THE IMPACT OF STUDY SKILLS COURSES ON

ACADEMIC SELF-EFFICACY IN COLLEGE STUDENTS

Brenna M. Wernersbach, Susan Crowley, and Carol Rosenthal - Utah State University

presented at the Utah University & Counseling Centers Conference, Park City, UT, October 29, 2010

Results

The drive to retain students has led many colleges and universities to implement study skills courses and workshops designed to help academically underprepared students succeed. The effectiveness of many of these programs in increasing student GPA and retention has been supported in previous research. However, the impact of these programs on academic self-efficacy, another predictor of academic success, has not been investigated.

The present study examined pre-post levels of academic self-efficacy in students enrolled in a study skills course compared to students enrolled in a general education course. In addition, the predictive power of academic self-efficacy on academic outcome and retention into the following semester was assessed.

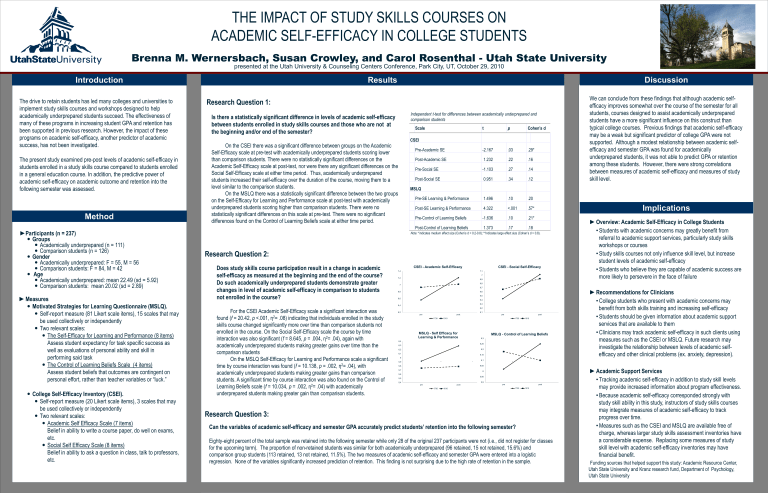

Research Question 1:

Is there a statistically significant difference in levels of academic self-efficacy between students enrolled in study skills courses and those who are not at the beginning and/or end of the semester?

On the CSEI there was a significant difference between groups on the Academic

Self-Efficacy scale at pre-test with academically underprepared students scoring lower than comparison students. There were no statistically significant differences on the

Academic Self-Efficacy scale at post-test, nor were there any significant differences on the

Social Self-Efficacy scale at either time period. Thus, academically underprepared students increased their self-efficacy over the duration of the course, moving them to a level similar to the comparison students.

On the MSLQ there was a statistically significant difference between the two groups on the Self-Efficacy for Learning and Performance scale at post-test with academically underprepared students scoring higher than comparison students. There were no statistically significant differences on this scale at pre-test. There were no significant differences found on the Control of Learning Beliefs scale at either time period.

Independent t-test for differences between academically underprepared and comparison students

Scale t

p

Cohen’s d

CSEI

Pre-Academic SE

Post-Academic SE

Pre-Social SE

Post-Social SE

-2.167

1.232

-1.103

0.951

.03

.22

.27

.34

.29*

.16

.14

.12

MSLQ

Pre-SE Learning & Performance

Post-SE Learning & Performance

Pre-Control of Learning Beliefs

1.496

4.322

-1.636

.10

<.001

.10

.20

.57*

.21*

Post-Control of Learning Beliefs 1.373

.17

.18

Note: *indicates medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.2-0.8); **indicates large effect size (Cohen’s d > 0.8).

Discussion

We can conclude from these findings that although academic selfefficacy improves somewhat over the course of the semester for all students, courses designed to assist academically underprepared students have a more significant influence on this construct than typical college courses. Previous findings that academic self-efficacy may be a weak but significant predictor of college GPA were not supported. Although a modest relationship between academic selfefficacy and semester GPA was found for academically underprepared students, it was not able to predict GPA or retention among these students. However, there were strong correlations between measures of academic self-efficacy and measures of study skill level.

Method

► Participants (n = 237)

Groups

Academically underprepared (n = 111)

Comparison students (n = 126)

Gender

Academically underprepared: F = 55, M = 56

Comparison students: F = 84, M = 42

Age

Academically underprepared: mean 22.49 (sd = 5.92)

Comparison students: mean 20.02 (sd = 2.89)

►Measures

Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ).

Self-report measure (81 Likert scale items), 15 scales that may be used collectively or independently

Two relevant scales:

The Self-Efficacy for Learning and Performance (8 items)

Assess student expectancy for task specific success as well as evaluations of personal ability and skill in performing said task

The Control of Learning Beliefs Scale (4 items)

Assess student beliefs that outcomes are contingent on personal effort, rather than teacher variables or “luck.”

College Self-Efficacy Inventory (CSEI).

Self-report measure (20 Likert scale items), 3 scales that may be used collectively or independently

Two relevant scales:

Academic Self Efficacy Scale (7 items)

Belief in ability to write a course paper, do well on exams, etc.

Social Self Efficacy Scale (8 items)

Belief in ability to ask a question in class, talk to professors, etc.

Research Question 2:

Does study skills course participation result in a change in academic self-efficacy as measured at the beginning and the end of the course?

Do such academically underprepared students demonstrate greater changes in level of academic self-efficacy in comparison to students not enrolled in the course?

For the CSEI Academic Self-Efficacy scale a significant interaction was found (f = 20.42, p <.001, η 2 = .08) indicating that individuals enrolled in the study skills course changed significantly more over time than comparison students not enrolled in the course. On the Social Self-Efficacy scale the course by time interaction was also significant (f = 8.645, p = .004, η 2 = .04), again with academically underprepared students making greater gains over time than the comparison students

On the MSLQ Self-Efficacy for Learning and Performance scale a significant time by course interaction was found (f = 10.138, p = .002, η 2 = .04), with academically underprepared students making greater gains than comparison students. A significant time by course interaction was also found on the Control of

Learning Beliefs scale (f = 10.034, p = .002, η 2 = .04) with academically underprepared students making greater gain than comparison students.

7,4

7,2

7

6,8

6,6

6,4

6,2

6,1

6

5,9

5,8

5,7

5,6

5,5

5,4

6,4

6,3

6,2

CSEI - Academic Self-Efficacy pre

1730 1010 post

MSLQ - Self Efficacy for

Learning & Performance pre

1730 1010 post

7,1

7

6,9

6,8

6,7

6,6

6,5

6,4

6,3

6,2

6,1

CSEI - Social Self-Efficacy pre

1730 1010 post

6,15

6,1

6,05

6

5,95

5,9

6,3

6,25

6,2

MSLQ - Control of Learning Beliefs pre post

1730 1010

Research Question 3:

Can the variables of academic self-efficacy and semester GPA accurately predict students’ retention into the following semester?

Eighty-eight percent of the total sample was retained into the following semester while only 28 of the original 237 participants were not (i.e., did not register for classes for the upcoming term). The proportion of non-retained students was similar for both academically underprepared (96 retained, 15 not retained, 15.6%) and comparison group students (113 retained, 13 not retained, 11.5%). The two measures of academic self-efficacy and semester GPA were entered into a logistic regression. None of the variables significantly increased prediction of retention. This finding is not surprising due to the high rate of retention in the sample.

Implications

►Overview: Academic Self-Efficacy in College Students

• Students with academic concerns may greatly benefit from referral to academic support services, particularly study skills workshops or courses

• Study skills courses not only influence skill level, but increase student levels of academic self-efficacy

• Students who believe they are capable of academic success are more likely to persevere in the face of failure

►Recommendations for Clinicians

• College students who present with academic concerns may benefit from both skills training and increasing self-efficacy

• Students should be given information about academic support services that are available to them

• Clinicians may track academic self-efficacy in such clients using measures such as the CSEI or MSLQ. Future research may investigate the relationship between levels of academic selfefficacy and other clinical problems (ex. anxiety, depression).

►Academic Support Services

• Tracking academic self-efficacy in addition to study skill levels may provide increased information about program effectiveness.

• Because academic self-efficacy corresponded strongly with study skill ability in this study, instructors of study skills courses may integrate measures of academic self-efficacy to track progress over time.

• Measures such as the CSEI and MSLQ are available free of charge, whereas larger study skills assessment inventories have a considerable expense. Replacing some measures of study skill level with academic self-efficacy inventories may have financial benefit.

Funding sources that helped support this study: Academic Resource Center,

Utah State University and Kranz research fund, Department of Psychology,

Utah State University

POSTER TEMPLATE BY: www.PosterPresentations.com