The Rise of Sparta: Spartan

Constitution and Spartan Way of

Life

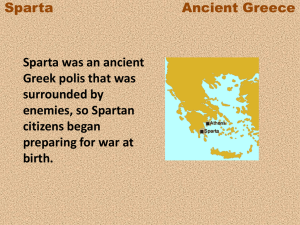

Geography Location

Geography

Location

Introduction

Webster’s has defined Spartans as “warlike,

brave, hardy, stoical, severe, frugal, and highly

disciplined.”

Even till today, calls up images of military

strength and prowess, and of a way of life

devoted single-mindedly to patriotic duty,

characterized by patriotism, courage in battle,

and tolerance for deprivation.

Introduction

“Admired in peace and dreaded in war”;

The most powerful and the most important state;

The polis was the center of a Greek man’s life;

Became a sort of a model for the philosophers

(Plato and Aristotle);

The leading power of the first international

organization

1.Brief History

Dorian newcomers from the north (10th)

entered the plain Laconia;

Local inhabitants were reduced to a status

of slaves called Helots.

Three traditional divisions of Greeks,

distinguished by the different dialects of Greek

they spoke:

• The Dorians,

• The Ionians,

• and the Aeolians.

1.Brief History

Troubled by difficulties in satisfying its needs from its own

territory, the Spartans sought a military answer to their

problems:

(1)Started the first Messenia War (730 – 710 B.C.): Messenia

became subject to Sparta, the local people became perioikoi,

or helots. (turned into one of largest of Greek states (over

3,000 square miles);

(2) This is a whole people with a sense of themselves, who think of

themselves as Mycenaeans. They are conquered and enslaved

and they become a critical part of the Spartan;

(3) The Second Messenian War (640-630 B.C.).

The potential risks of the helot system:

• They are permanently dissatisfied, angry

• They are permanently thinking about

somehow getting free and permanently,

therefore, presenting a threat to whatever

the Spartan regime is at the time.

2. The Helots

The Helots led a miserable life as described by the

poet Tytaeus who fought in the Messenia War:

Like asses exhausted under great loads: under painful

Necessity to bring their masters full half the fruit their

Ploughed land produced.

Sparta becomes a slave holding state like no other Greek state.

• Now, there was slavery all over the ancient world. There was

no society that we know of in the ancient world that was without

slavery and Greece was no different, but in the period we're

talking about there were not very many slaves among the

Greek states as a whole, and there was certainly nothing like

what the Spartans did.

• To have a system of life that allowed the Spartan citizens not to

work in order to live; no other Greek state would have that. If

you want to think about Greek slavery in the seventh century

B.C., think about farmers who themselves worked the fields,

and are assisted in their work in the fields by one or two slaves.

3. Insecure Foundation

Sparta rested on insecure foundations. The

Helots later outnumbered the Spartans.

The large number of the helot workers, Sparta’s

absolute dependence on them, and the fear of a helot

rebellion led to extremely harsh measures. Helots

were allowed to be killed without a penalty. Deprived

of their freedom and fertile territory, the Messenian

helots were ever after on the lookout for a chance to

revolt against the Spartan overlords. Civil unrest was

a threatening factor.

The Spartan system will be Spartans at home,

training constantly for their military purposes,

never working any fields, never engaging in

trade or industry, others doing that for them.

3. Lycurgus

3.1 Background

After the Second Messenian War, Sparta fell into

social chaos. Amid such social surroundings,

Lycurgus reformed the Spartan system and founded

the typical Spartan institution. This is the institutions

which made Sparta so successful for so many

centuries from the eighth century BC right down to

the time of Alexander the Great, almost 500 years.

3.2 Lycurgus: Greek Great Lawgiver

Lycurgus was a great lawgiver and one of the seven wise

men in Greek history. Lycurgus himself was not the royal blood

but was the uncle of the King of Sparta and acted as his

regent. Lycurgus was said to be a man of enormous integrity

and both Lycurgus and Solon set the model of “Nothing in

Excess” and “Never to Abuse Power”.

Lycurgus

Biography

(800 BC–730 BC)

Reform of Lycurgus

Bas-relief of Lycurgus,

one of 23 great lawgivers

depicted in the chamber of

the U.S. House of

Representatives.

3.3 Travelling

And so Lycurgus was asked to undertake his reforms.

Now realizing that Sparta was in need of reform,

Lycurgus set off a series of travels and went first to

Crete. The Cretans were related to Spartans; both of

them were Dorians and came from the northern Greece

to the South after the fall of the Mycenaean. Lycurgus

studied the characteristic institutions of Crete.

Then he went to Ionian, Asia Minor where the Iliad

was composed, and there he also studied their Greek

institutions and compare the softness of love of luxury

that characterizes the Ionians with the rigorous war-like

society of Crete.

And then he also went to Egypt. He then came back

to Sparta and carried out his reforms.

4. The Reform of Lycurgus

4.1 The ideal of reform

From the very start, reforms undertaken by

Lycurgus rested upon the ideal of achieving

absolute equality among all Spartans. In the

Archaic Age, the bane of almost all Greek city-states

was civil war brought about by economic and social

disparity. Lycurgus therefore sought to avoid this

through his reforms by making every Spartan

equal. He aimed to establish a balanced

constitution and it was this very balanced

constitution of Sparta attributed to Lycurgus was

very much admired by the founders of many later

countries.

4. The Reform of Lycurgus

Balanced in itself all the elements essential to government: monarchy (,

democracy, and aristocracy

(1) Monarchy: Rule by one individual, answers the need for strong unified

executive authority. In a time of crisis of warfare, every government

has the need for strong executive authority for a single individual to be

able to hold the reigns for the central power.

(2) Democracy: Answers the need for a broad base of popular support.

Such a broad base of public support serves the unity of the central

power.

(3) Aristocracy: There must be the room for the guidance of the state by

a collection, a small collection of best individuals. This is aristocracy,

rule by the best which answers the need for the making of policy by a

small group of outstanding citizens, the best morally, and the best

intellectual.

4. The Reform of Lycurgus

4.3 Three Parts of Sparta Constitution:

This balanced institution was considered by

many, including Plato and Aristotle, to be a model

for other poleis. The Spartan constitution or rhetra

in Greek language, in its developed form had three

parts:

(1) The dual kingship;

(2) The council of elders, or Gerousia;

(3) And the Assembly.

4. The Reform of Lycurgus

4.3.1 The Dual Kinship: The Monarchy

(1)Two kings from separate royal families: equal power and held office

for life.

(2) The kings’ power in domestic matters was strictly limited. But in time

of war, the kings were commander-in-chief invested with enormous

power. They had the right of announcing a war upon whatever

country they chose, and in the field they exercised unlimited right of

life and death and had a bodyguard of 100 men.

(3) Later, however, their power was further restricted by a reform that

allowed only one of them, chosen by the people, to lead the army in a

given campaign, and held him responsible to the community for his

conduct of the campaign. The kings held certain important priesthoods,

but they did not have judicial power over criminal cases.

(4)Their main source of income was from royal land that they held in the

territory of the perioikoi. They were ceremonially honored with the first

seat at banquets, were served first, and received a double portion.

One king acted as a check on his colleague.

4. The Reform of Lycurgus

4.3.2 The Assembly: Democracy

The Assembly of all Spartans was the ultimate sovereign; it

decides all matters of war and peace.

It was made up of Spartan male citizens over the age of thirty.

Citizenship depended upon successful completion of the course of

training and education which was provided by the state, and upon

election to, and continuing membership in a mess .

The Assembly elected the Gerousia the Ephorate and the other

magistrates , decided disputed successions to the kingship, and

determined matters of war and peace and foreign policy.

Debate was not allowed, only assent or dissent by acclamation to

measures presented by the Gerousia. Thus, theoretically Sparta was

a democracy, but the power of the people in the Assembly was

strictly limited, and the Assembly’s decisions were subject to

overturn by the Geriousia.

4. The Reform of Lycurgus

4.3.3 The Gerousia: Aristocracy

The Gerousia guided policy, particularly foreign policy.

The Gerousia elected by the Spartan Assembly consisted of thirty

members, including two kings.

This was the Senate of Sparta, literally the Council of Old Men for

members had to be over sixty years of age and were chosen

for their outstanding abilities and service to Sparta. They

served for life.

The Gerousia acted as a supreme court. It could declare a law

passed by the Assembly as unconstitutional. And if the

decision of the Assembly was “unjust,” the Gerousia had the

power to overturn it.

4. The Reform of Lycurgus

4.3.4 the Ephors:The Guardians

Another ruling entity was formed after Lycurgus – the Ephors.

Five Spartans were elected annually for a one-year term. They

were the guardians of the rights of the people and a check on

the power of the kings. So, the creation of ephors further limited

the power of the two kings. They also enforced the Spartan

way of life and its educational system. Although a variety of

duties came to be assigned to the ephors in classical times, the

most basic of their duties reveals the primary function of the

office. This was the monthly exchange of oaths between the

ephors and the kings: the ephors swore to uphold the rule of

the kings as long as the kings kept their oath, while the kings

swore to govern in accordance with the laws. Thus they

provided a check on the power of the two kings.

4. The Reform of Lycurgus

4.4. Result: Balanced Constitution

By the Classical period, these constitutional

reforms had resulted in a balanced constitution

that combined the merits of monarchy, democracy,

and aristocracy. The ability to compromise and to

bring into harmony the interests of competing groups

had enabled the Sparta to avoid the phase of

tyranny through which many other Greek poleis

passed in order to achieve similar reforms. Sparta’s

balanced constitution was the admiration of other

Greek cities and of the Founders of the United

States.

5. The Spartan Way of Life

5.1 Civil Virtue:

Lycurgus understood that even the best

constitution will fail unless it is vitalized by

civic virtue. He defined civic virtue as “the

willingness of the individual to subordinate

his interest to the good of the community”.

To instill civic virtue was the goal of the

educational system –the Spartan way of life

– attributed to Lycurgus.

5. The Spartan Way of Life

5.2 Childhood

In the Spartan system, the polis and its welfare

was all in all. Individual and family interests and

ambitions were to be put aside to create a society

focused on the common good. A Spartan newborn

had first to be formally “recognized” by the five

Ephors. Unrecognized and very sick infants were

“exposed”—abandoned to die. “Recognized”

infants were given a plot of land, to be worked by

slaves (helots). A Spartan child was raised by his

mother until the age of seven.

5. The Spartan Way of Life

5.3 At Seven

At seven, the child began to be educated in a system called

the agoge (the Greek word comes from the verb ago, “to lead,”

and denoted a system of training and a way of life). The agoge

was carefully planned to weaken ties to family and to

strengthen a collective identity. When they entered the

agoge, boys were divided into age groups and lived under the

immediate supervision of older boys. Although they were taught

the rudiments of reading and writing, the focus of the agoge

was on rigorous physical training to develop hardiness and

endurance. They were also acculturated to Spartan values by

listening to patriotic choral poetry and tales of bravery and

heroism at the common meals.

5. The Spartan Way of Life

5.4 At Twelve

At age twelve, the agoge became increasingly more military

in form and more demanding. The boys were allowed only a

single cloak for winter and summer, required to sleep in beds

that they made themselves from rushes picked from the

Eurotas River, and fed meager rations that they were expected

to supplement by stealing (if caught, they were whipped for

their failure to escape detection). On occasion they attended

the men’s messes in preparation for their later election to one

of these groups. To further their acculturation, they were

expected to develop homosexual “mentor” relationships with

one of the hebontes, men between the ages of twenty and

thirty who played a quasi-parental role in socializing their young

charges.

5. The Spartan Way of Life

5.5 At Eighteen

At eighteen, Spartan boys were sent out on a mission to

prove their manhood by killing the largest helot they could

find. For those who successfully completed the agoge, the next

step was to gain acceptance in the fundamental institution of

adult Spartan male life, the mess, or sysitia. A mess

consisted of a group about fifteen men of mixed ages who ate

and fought together throughout their lives, and who lived

together until the age of thirty, when they were allowed to set

up their own households. Entry into a mess required

unanimous vote by its members. It was a crucial vote, for full

citizenship depended upon membership. Those who failed to

be elected were relegated to an inferior status, possibly to be

indentified with the hpomeiones, literally “inferior.”

5. The Spartan Way of Life

5.5 At Eighteen

Upon election to a mess, the young men, now classed as

hebontes, were still not in possession of full citizenship rights.

While they could probably attend the Assembly and vote, they

remained under the close supervision and control of the

paidonmos. The hebontes were encouraged to marry, but they

were not permitted to live with their wives until they

reached the age of thirty. As a result, they spent for more

time and developed closer emotional ties with their young male

charges, than with their wives. This was the period in which

they were most active in military service, and, as we saw above,

they were also subject to serve in the Krypteia.

5. The Spartan Way of Life

5.6 At the Age of Thirty

At the age of thirty, the Spartan became a full

citizen and was expected to move out of the

barracks and set up his own households. He also

became eligible to hold office. But he continued to

take his main meal in his mess, and his military

obligations continued until the age of sixty. At that

time he became eligible for the Gerousia and no

longer had military obligations. He still ate in his

mess, however, and was expected to participate

actively in the training and disciplining of the

younger men and boys.

Marble statue of a helmed hoplite (5th century BC)

5. The Spartan Way of Life

5.7 All in all

It would be seen that the entire Spartan

way of life was directed toward keeping the

Spartan army at tip-top strength. It became a

warlike society in which equality was at the

center of the Spartan way of life. All

Spartans owned the same amount of land

and a set number of helots. Personal

possessions were freely shared.

6. The Spartan Women

6.1 The Spartan Girl

Spartan girls were educated in the same ideals as

Spartan boys, which is quite different from other

poleis. For example, in Athens, girls were not

educated, and historical evidence shows that

Athenian women lived so completely separated from

the men that they even had their own dialect.

Spartan women enjoyed a status, power, and

respect that were unknown in the rest of the

classical world.

6. The Spartan Women

6.2 Households

With their husbands so rarely at home, Spartan women directed

the households, which included servants, daughters, and sons until

they left for their communal training. They controlled their own

properties, as well as the properties of male relatives who were away

with the army. Unlike women in Athens, if a Spartan woman became

the heiress of her father because she had no living brothers to inherit

(an epikleros), the woman was not required to divorce her current

spouse in order to marry her nearest paternal relative. Unlike Athenian

women who wore heavy, concealing clothes and were rarely seen

outside the house, Spartan women wore short dresses and went

where they pleased rather than being secluded in the home. Nor did

the Spartans follow the customary practice of most poleis of marrying

girls at puberty; in Sparta marriage and childbearing were put off until

girls reached physical maturity (at eighteen to twenty years old), again

in order to ensure the best reproductive outcome.

6. The Spartan Women

6.3 Marriage

The girl was carried off, her hair was cut, and she was

dressed as a boy by her “bridesmaids”; she was then left in a

dark room where her husband-to-be would visit her. If

pregnancy resulted, the marriage was valid, but the husband

continued in his mess until he reached the age of thirty, visiting

his wife only at night and by stealth. The ancient sources report

that this regime was adopted to heighten sexual attraction and

increase the vigor of any resulting infants. Another view is that

it would ensure that the couple would see each other primarily

as sexual partners and that the husband would not invest

himself emotionally in the welfare of his wife and family to the

detriment of his military duties.

6. The Spartan Women

6.3 The Marriage: Description by Plutarch

Plutarch reports the peculiar customs associated

with the Spartan wedding night:

“The custom was to capture women for

marriage(...)The so-called 'bridesmaid' took charge

of the captured girl. She first shaved her head to the

scalp, then dressed her in a man's cloak and

sandals, and laid her down alone on a mattress in

the dark. The bridegroom—who was not drunk and

thus not impotent, but was sober as always—first

had dinner in the messes, then would slip in, undo

her belt, lift her and carry her to the bed.

6. The Spartan Women

6.4 The Concept of Adultery

In Spartan law and practice, the concept of adultery did not

exist. It was acceptable for a husband to loan his wife to his

friends if he wanted no more children himself, or to borrow the

wife of another men for reproductive purposes. Old men with

young wives were expected to provide a young man as a

sexual partner for their wives. Such practices of course

fostered reproduction: the potential of female fertility was fully

exploited even when the luck of the marriage draw did not favor

it. Other Greeks looked askance at these practices and at the

“freedom” allowed to Spartan women and viewed Spartan

women as licentious. But it was not the women who were in

control; in each case, it was the husband who arranged for and

sanctioned such extramarital relationships. These relationships

can be looked upon as logical extension of the general Greek

conception of women as property, in the context of the Spartan

practice of sharing resources.

6. The Spartan Women

Spartan women ran the farm and disciplined the

helots. In Sparta, commerce is forbidden. No gold

or silver was permitted and Luxuries were banned.

There were no written laws and, hence, no lawyers.

All Spartan citizens were expected to put service to

their city-state before personal concerns because

Sparta’s survival was continually threatened by its

own economic foundation, the great mass of helots.

7. The Cost of Utopia Martial State

Reforms by Lycurgus resulted in a powerful Sparta. In the

Classical Period, Sparta became the preeminent military power in

Greece; its fighting force was remarkably disciplined and obedient to

the dictates of the Spartan state. This contributed a lot to the success

of the Greek army against the Persians which we come back in the

later chapters. The Spartans were also very much admired and

respected as the champions of liberty in Greece and also for their

military skill and courage in battles. Their alliance with other Greeks

(the Peloponnesian League) made them the most formidable military

power in Greece. But even more important was the Spartan success

in achieving good government through the institutions of Lycurgus. In

antiquity the Spartan were widely admired for their courage and

military prowess, and my Greeks – and later, Romans—had a

romantic fascination with the Spartan way of life. Many followers often

adopted Spartan fashions in dress and the long hair that was

Spartan custom. Among these admirers were some of our most

important sources – Xenophon, Plato, Aristotle, and Plutarch. For

example, Plato based his ideal state on certain characteristics of

Sparta.

7. The Cost of Utopia Martial State

Viewed from the standpoint of the values of Athens and other, more liberal

societies, there were definite weakness in the Spartan way of life.

First, the Spartan paid a high price for their security. Their way of life was

marked by extreme austerity. They were notorious for the simplicity of their

meals consisting of barley, cheese, figs, and wine, and supplemented by

occasional bits of meat. In order to ensure absolute equality, commerce is

forbidden. No gold or silver was permitted and Luxuries were banned.

Second, Spartan society was, as might be expected, quite conservative:

innovation and foreign influence were firmly resisted. In contrast to the

Athenian fascination with the poetry of tragedy and comedy and the love of

rhetorical display, the Spartans took pride in laconic (terse) habits of speech

and confined their literary and music appreciation to patriotic songs, such as

those of Tyrtaeus. By the Classical period the earlier achievements in the crafts

had disappeared; even monumental public building had ceased. Third, the

Spartan way of life is incompatible with their own aims. The agoge, with its

emphasis on strict control and obedience, did not foster the development of

individual judgment, and we shall see in later Greek history many instances of

Spartan at a loss to handle unusual situations. Nor were the Spartans immune

to the temptations of luxury.

7. The Cost of Utopia Martial State

Another thing which has much to do the Spartan lifestyle is its

demographic difficulties—a shrinking population. Sparta was the

only Greek state in which male infanticide was institutionalized.

Moreover, many deaths can be explained by the Spartan soldier’s

obligation to stand his ground and give his life for his country, rather

than surrender. This ideal was reinforced by peer pressure,

epitomized by statements attributed to Spartan women such as that of

the mother who told her son as she handed him his shield to come

home “either with this or on this.”

In addition to high rate of infant and juvenile mortality found

throughout the ancient world, the Spartan problem was aggravated by

their unusual marriage practices. Women married only several years

after they became fertile; opportunities for conjugal intercourse were

limited; husbands were continuously absent at war or sleeping with

their army groups when wives were in their peak childbearing years;

and both sexes engaged in a certain amount of homosexual,

nonprocreative sex. Sparta’s population problem was also

accelerated at times by natural disaster, economic problems, and the

emigration of men.

Lycurgus was the son of the king Eumenos.

After the death of his father, his older brother

Polydektes took the throne. Not much later, he also

died and Lycurgus became king. The widow of his

brother, an ambitious and unhesitating woman,

offered him to marry her and kill her unborn child.

Lycurgus, knowing her character and being afraid for

the life of the child, pretended to accept her offer. He

said to her to bear the child and he would disappear

it, as soon as the child was born. But when the time

came, he took the infant boy at the

Agora, proclaimed him king of the Spartans and

gave him the name Charilaos (Joy of the people).

When the widow learned what happened, she

started plotting against Lycurgus, who left Sparta in

order to avoid bloodshed.

He first went to Crete and then to Asia and Egypt and later to Libya, Spain

and India. In every country that he visited, he studied their civilization, history

and constitutions.

After many years Lycurgus returned to

Greece and visited Delphi to question the oracle,

if the constitution he had prepared to apply in

Sparta was good and received approval with

the answer that "he was more God than

man". He then returned home and found his

nephew Charilaos, a grown man and king of

Sparta.

In order to persuade the Spartans to

accept his laws, which demanded a lot of

sacrifices, he bred two small puppies, the

one indoors with a variety of foods and the

other he trained it for hunting. He then

gathered the people and showed them that

the untrained dog was completely useless.

But if Lycurgus succeeded to persuade

the poor people, he did little for the rich, who

tried everything to oppose him. One of them,

a youth named Alkander, in the Agora tried

to hit him with his stuff and when Lycurgus

turned his head, he was hit in the eye and

lost it. Lycurgus did not prosecute him, but

took him as his servant, giving him the

opportunity to discover his character. Indeed

Alkander became later a devoted disciple.

When his laws were accepted, he made

Spartans swear that they would not be

changed until he returns and left again.He

never came back, making sure that his

laws would not change.

He died at Delphi and according to some

in Crete and it is said that before his death,

he asked his body to be burned and the

remains to be scattered in the wind.

Lycurgus thus did not permit even his dead

body to return.

The End