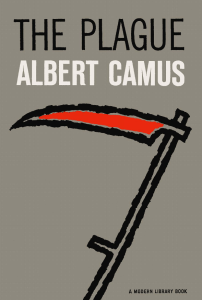

Albert Camus` The Plague

advertisement

The Plague Albert Camus Albert Camus, 1913-1960 http://www.flickr.com/photos/martyn/12764900/sizes/m/in/photostream/ ‘The Plague is Albert Camus’ most successful novel. It was published in 1947, when Camus was thirty-three, and was an immediate triumph...Camus’ public standing guaranteed his book’s success. But its timing had something to do with it too. By the time the book appeared, the French were beginning to forget the discomforts and compromises of the four years of German occupation... In this context, Albert Camus’s allegory of the wartime occupation of France reopened a painful chapter in the recent French past, but in an indirect and ostensibly apolitical key. It thus avoided arousing partisan hackles, except at the extremes of Left and Right, and took up sensitive topics without provoking a refusal to listen.’ Tony Judt, Introduction, The Plague, p viii ‘The peculiar events that are the subject of this history occurred in 194- in Oran. The general opinion was that they were misplaced there, since they deviated somewhat for the ordinary. At first sight, indeed, Oran is an ordinary town, nothing more than a French Prefecture on the coast of Algeria’. P5 ‘Our fellow citizens work a good deal but always in order to make money. They are especially interested in trade and first of all, as they say, they are engaged in business. Naturally they also enjoy simple pleasures: they love women, the cinema and sea bathing. But they very sensibly keep these activities for Saturday evening and Sunday, while trying on other days of the week to earn a lot of money.... You will say no doubt that this is not peculiar to our town and that when it comes down to it, people today are all like that... But there are towns and countries where people do occasionally have an inkling of something else. On the whole it does not change their lives; but they did have this inkling and that is positive in itself. Oran, on the other hand, appears to be a town without inklings, that is to say, an entirely modern town.’ pp 5-6 ‘On the afternoon of the same day, as he was starting his surgery, Rieux had a visit from a young man, a journalist who, he was told, had called already to see him that morning. His name was Raymond Rambert... He came straight to the point. He was doing an investigation for a large Parisian newspaper about the living conditions of the Arabs and wanted information about their state of health. Rieux told him that their health was not good; but before going further, he wanted to know if the journalist could tell the truth.’ p 11 ‘“I can only countenance a report without reservations, so I shall not be giving you any information to contribute to yours.” “You’re talking the language of Saint Just,” the journalist said with a smile. Without raising his voice Rieux said that he knew nothing about that but that it was the language of a man weary of the world in which he lived, yet who still had some feeling for his fellow men and was determined for his part to reject any injustice and any compromise.’ p12 ‘It was as though the very soil on which our houses were built was purging itself of an excess of bile, that it was letting boils and abscesses rise to the surface, which up to then had been devouring it inside. Just imagine the amazement of our little town which had been so quiet until then, ravaged in a few days, like a healthy man whose thick blood had suddenly rebelled against him!’ p15 ‘There have been as many plagues in the world as there have been wars, yet plagues and wars always find people equally unprepared. Dr Rieux was unprepared, as were the rest of the townspeople, and this is how one should understand his reluctance to believe... He tried to put together in his mind what he knew about the disease. Figures drifted through his head and he thought that the thirty or so great plagues recorded in history had caused nearly a hundred million deaths. But what are a hundred million deaths? When one has fought a war, one hardly knows any more what a dead person is.’ p 31 ‘And if a dead man has no significance unless one has seen him dead, a hundred million bodies spread through history are just a mist drifting through the imagination.... ten thousand dead equals five times the audience in a large cinema. That’s what you should do. You should get all the people coming out of five cinemas, take them to a square in the town and make them die in a heap; then you would grasp it better... In Canton, seventy years ago, forty thousand rats died of plague before the pestilence affected the human inhabitants. But in 1871 they didn’t have any means of counting rats.’ p 31 ‘Thus the first thing that the plague brought to our fellow-citizens was exile... Then we knew that our separation was going to last, and that we ought to try to come to terms with time. In short, from then on, we accepted our status as prisoners; we were reduced to our past alone and even if a few people were tempted to live in the future, they quickly gave it up, as far as possible, suffering the wounds that the imagination eventually inflicts on those who trust in it’. p 56 ‘“So I have a plan for organizing voluntary health teams. Appoint me to take charge and we can leave the authorities out of it. In any case, they are too busy to cope. I have friends all over the place, and they will form the core. And naturally, I shall take part myself.” “Of course,” Rieux said, “as you can imagine I am only too happy to accept. One needs help, especially in this job. I will be responsible for getting the Prefecture to accept the idea. In any case they have no choice. But...” Rieux thought. “But the work might be fatal, you know that. I still have to warn you. Have you really thought about it?” p96 ‘It is not the narrator’s intention to attribute more significance to these health groups than they actually had. It is true that nowadays many of our fellow citizens would, in his place, succumb to the temptation to exaggerate their role. But the narrator is rather inclined to believe that by giving too much importance to fine actions one may end by paying an indirect tribute to evil, because in doing so one implies that such fine actions are only valuable because they are rare, and that malice, or indifference are far more common motives in the actions of men... In reality it was no great merit on the part of those who dedicated themselves to the health teams, because they knew that it was the only thing to be done and not doing it would have been incredible at the time.’ pp 100-101 “A lot of new moralists appeared in the town at this moment, saying that nothing was any use and that we should go down on our knees. Tarrou, Rieux and their friends could answer this or that, but the conclusion was always what they knew it would be: one must fight, in one way or another, and not go down on one’s knees. The whole question was to prevent the largest possible number of people from dying and suffering a definitive separation. There was only one way to do this, which was to fight the plague. There was nothing admirable about this truth, it simply followed as a logical consequence.” p 102 ‘Cottard looked at Tarrou without understanding. The other man explained that too many people were not doing anything, that the epidemic was everybody’s business and that they all had to do their duty... “Why don’t you join us, Monsieur Cottard?” Cottard got up looking offended and picked up his round hat. “It’s not my job.” Then with a tone of bravado: “In any case, this plague is doing me a favour, so I don’t see why I should be involved in getting rid of it. Tarrou struck his forehead, as though suddenly realizing something: “Of course, I’m forgetting; you would be arrested otherwise.”’ p 120 ‘When the epidemic levelled out after August, the accumulated number of victims was far greater than the capacity of our little cemetery... Soon it was also necessary to take those who had died from the plague off to the crematorium. But for this they had to use the old incinerating ovens to the east of the town, outside the gates. The guard post was moved further out and a town hall employee made the task of the authorities much easier by advising them to use the tramline which had formerly served the seaside promenade but was now lying idle. →→→ To this end, they made some alterations to the interior of the trucks and engines by taking out the seats, and redirected the track to the oven which now became the end of the line... One could hear the vehicles still bumping along on a summer’s night, laden with flowers and corpses. By morning, at least in the early days, a thick, foulsmelling vapour would be drifting over the eastern quarter of the town.’ p 137 ‘Finally they entered the stadium. The stands were full of people and the field was covered with several hundred red tents inside which one could see, from a distance, bedding and bundles... “What do they do all day?” Tarrou asked Rambert. “Nothing.” Almost all of them were empty handed, with their arms hanging by their sides. This vast assemblage of men was curiously silent. “In the early days, you couldn’t hear yourself speak here,” said Rambert. “But as time goes by, they talk less and less.” →→→ If one is to believe his notes, Tarrou understood them and imagined them in the beginning piled into their tents, kicking their heels or scratching their bellies, shouting out their anger and their fear whenever they found a willing ear. But as soon as the camp became over-populated, there were fewer and fewer willing ears. There was nothing left for it but to be quiet and watchful.’ p 185 ‘“That is why this epidemic has so far taught me nothing except that it must be fought at your side. I have absolute knowledge of this – yes Rieux, I know everything about life, as you can see – that everyone has inside it himself, this plague, because no one in the world, no one, is immune. And I know that we must constantly keep a watch on ourselves to avoid being distracted for a moment and find ourselves breathing in another person’s face and infecting him... Yes indeed Rieux, it is very tiring to be a plague victim. But it is still more tiring not to want to be one.”’ p 195 ‘As he listened to the cries of joy that rose above the town, Rieux recalled that this joy was always under threat. He knew that this happy crowd was unaware of something that one can read in books, which is that the plague bacillus never dies or vanishes entirely, that it can remain dormant for dozens of years in furniture or clothing, that it waits patiently in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, handkerchiefs and old papers, and that perhaps the day will come when, for the instruction or misfortune of mankind, the plague will rouse its rats and send them to die in some well-contented city.’ pp 237-238 ‘The stricken city is Oran in Algeria, but it's also France, during the Second World War. This France, however, stands for Everywhere, a banal small place where history unfortunately takes a terrible turn. Far from being a study in existential disaffection... The Plague is about courage, about engagement, about paltriness and generosity, about small heroism and large cowardice, and about all kinds of profoundly humanist problems, such as love and goodness, happiness and mutual connection. →→→ Camus published the novel in 1947 and his town's sealed city gates embody the borders imposed by the Nazi occupation, while the ethical choices of its inhabitants build a dramatic representation of the different positions taken by the French. He etches with his sharp, implacable pen, burning questions that need to be faced now more than ever in the resistance to terrorism. Perhaps even more than when La Peste was published, the novel works with the stuff of fear and shame, with bonds that tie and antagonisms that sever.’ Marina Warner, The Guardian, 2003