Some Damned Foolish Thing in the Balkans

advertisement

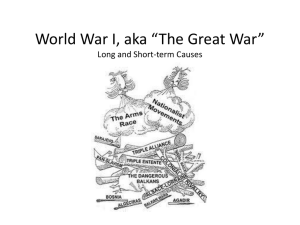

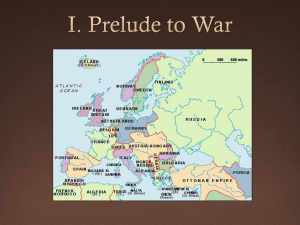

| ORIGINS OF THE GREAT WAR (1870-1914) 1 1. “Thirty Years War” – Europeans wage “war of all against all” (1914-45) 2. End of European global hegemony 3. Collapse of empires – revolution 4. Communism & Fascism emerge 5. Economic consequences of the peace 6. Industrialized total war – end of progress 7. Restructuring of society 2 “The First World War was a tragic and unnecessary conflict. Unnecessary because the train of events that led to its outbreak might have broken at any point during five weeks of crisis that preceded the first clash of arms, had prudence or common goodwill found a voice; tragic because the consequences of the first clash end the lives of ten million human beings, tortured the emotional lives of millions more, destroyed the benevolent and optimistic culture of the European continent, and left, when the guns at last fell silent four years later, a legacy of political rancour and racial hatred so intense that no explanation of the causes of the Second World War can stand without reference to those roots. The Second World War, five times more destructive of human life and incalculably more costly in material terms, was the direct outcome of the First…” – John Keegan, The First World War 3 1. 2. 3. 4. nationalism (pan-Slavism) alliance system imperial rivalries militarism & “arms race” An analysis of these causes suggests war was inevitable and out of the hands of human actors. “Nothing is inevitable until it happens.” - A.J.P. Taylor, British historian 4 pan-Slavic nationalism was one of the few causes that Russia’s ruling classes supported (religious, cultural similarities) – Russia was horribly disunited in the early 1900s Since gaining independence from Ottomans (1886), Serbia desired to unite the Slavic peoples in a “greater Slavia” (Yugoslavia) – many Slavs lived inside the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Russian support of these peoples were the real menace to the Hapsburgs. A series of crises and small wars rocked the Balkans in 1908, 1912 and 1913 – in each case, Russia backed down from supporting the Serbians. Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia in 1908 to prevent nationalist uprisings on its borders. 5 “Europe today is a powder keg and the leaders are like men smoking in an arsenal…A single spark will set off an explosion that will consume us all…I cannot tell you when that explosion will occur, but I can tell you where…Some damned foolish thing in the Balkans will set it off.” -Otto von Bismarck, 1890s “The Balkan crisis of 1914 proved fatal because two others had gone before it, leaving feelings of exasperation in Austria, desperation in Serbia, and humiliation in Russia.” -- Palmer, Colton and Kramer 6 Nationalist movements in the Balkans were a threat to the stability of both AustriaHungary and the Ottoman Empire. 7 The collapse of Ottoman rule in the Balkans was viewed from Moscow as an opportunity to expand south into the Mediterranean. This “Eastern Question” had dominated European diplomacy since the Crimean War – if not the Ottomans to rule, then who? 8 …What Greece had done in the Peloponnese in the 1820s, what Belgium had done in Flanders in the 1830s, what Piedmont had done in Italy in the 1850s and what Prussia had done in Germany in the 1860s – that was what the Serbs wanted to do in the Balkans in the 1900s: to extend their territory in the name of “South Slav” [Yugoslavia] nationalism. The success or failure of small states to achieve independence or enlargement always hinged, however, on the constellation of great power politics. – Niall Ferguson, The Pity of War (1999). 9 Central Powers (Triple Alliance) 1. 2. 3. Germany Austria-Hungary Italy? (had territorial grievances with A-H) After 1870, Bismarck had always maintained a skillful policy of avoiding encirclement by being in an alliance with at least 2 of the continental powers, thus always isolating France. After 1890,Kaiser Wilhelm II’s foreign policy (“place in the sun”), support of Ottoman Empire (i.e. Berlin-Baghdad Railway), and allowing Russian alliance to lapse, forced Germany to rely more on their alliance with Austria-Hungary 10 Entente Cordiale (not an alliance) 1. France (mutual defense alliance with Russia) 2. Russia (industrial assistance and investment from France to counter Germany) 3. Britain? (distrusted Russian ambitions in Mediterranean, but left with no alternative?) 11 Entente Cordiale (not an alliance) German foreign policy, empire-building after 1890 and creation of a naval fleet was viewed in London with concern. This drew them into a closer association with France (almost went to war in 1898 in Fashoda – but found diplomatic solution. By 1904, France and Britain had an understanding or “entente”). In 1907, France brokered the AngloRussian Accord. Britain was feeling pressure of economic competition from Germany and losing prestige, especially after their unpopular South African War (Britain’s Iraq???). This sense of insecurity caused them to abandon “splendid isolation” and become more involved in the continent. After 1905 Revolution and humiliation against Japan, Russia relied heavily on French capital and expertise to modernize, industrialize and improve her armed forces (this was an alliance of polar opposites: democracy and tsarism); France needed a strong ally on Germany’s eastern border 12 This political cartoon shows the German perspective of the Anglo-French entente. John Bull (Britain) is shown being escorted away from a possible friendship with Germany by the prostitute (France). The sword hidden under the German’s cloak suggests there will be future consequences for this foolish decision. 13 14 Britain viewed Germany as a threat to its global empire and prestige as the leading economic power in Europe. Fearing encirclement, Germany twice attempted to break up France and Britain’s relationship by threatening French imperial ambitions in North Africa (Morocco , 1905 and 1911). In the Second Moroccan Crisis (1911) Germany used “gun boat diplomacy” to gain territorial concessions in the Congo from France. 15 Russia had fought a series of wars since 1870s against the Ottomans and had carved out territories from the “sick man of Europe”, and supported the cause of Serbia nationalism for strategic reasons – it would help them gain influence in the Balkans and gain access to the Mediterranean. Austria-Hungary was in survival mode, and Serbian nationalism and terrorist organizations inside the empire threatened its existence, but were not powerful enough without Russian support to seriously disrupt the empire. Russia was not prepared, nor willing to fight over the Balkans in 1908 (Bosnia) or 1912-13 (Balkan Wars) – so Serbian ambitions were unsuccessful. 16 To thwart its rivals, and gain more influence in the Balkans and Middle East, Germany financed a railway in the Ottoman Empire and increasing lent its military expertise and capital to the Turks. One of the more dramatic forms of the rivalry was a German plan for a Berlin to Baghdad railway, a counter to the British scheme of the Cape to Cairo line. The German plan involved pushing Russian influence out of the Balkans, cutting Russia off from the Mediterranean by control of the Dardenelles, and in opening up a way for Germany to expand towards the Persian Gulf and India. 17 Britain and France were competitors in Africa until 1898, when after nearly starting a war (Fashoda Incident), compromised and found a diplomatic solution – Britain gained East Africa, France gained North and Equatorial Africa. Neither could afford war in 1898; both were increasingly concerned with German power and agreed to carve up Africa to the exclusion of Germany. Britain and Russia also had conflicting imperialist aims in the Middle East (Dardanelles, Iran), but France mediated between the two, wanting to create strong allies against Germany. By 1914, imperialistic rivalries resulted in heightened tensions, distrust, and stronger reliance on allies. It also encouraged states to invest heavily in arms, and contributed to the sense of impending doom, that war would come sooner or later. 18 Historians claim that the expectation of war and fervent militarism among the citizens of the Great Powers made general war more likely. By 1914, Europe was two heavily armed power blocs. Most states had adopted compulsory military service and had millions of trained reservists. “gun boat diplomacy” and the exercising of military power was a legitimate means of solving international disputes in the 19th century. Why should it be different now? Some revisionist historians (i.e. Ferguson, 1998) have convincingly argued that militarist attitudes were not the norm by 1914, and that military spending and support for war was not the norm. Britain was woefully unprepared for war when it came, and Germany’s military spending had decreased substantially. 19 Anglo-German Naval Arms Race - Germany had tried, but could not maintain, to build a navy to rival Britain. According to American military strategist, Mahan, naval supremacy was the key to global domination throughout history. Germany’s attempt to build a massive fleet was viewed as an act of aggression in London, but by 1907-08, Germany had abandoned these plans – the army was more vital to its survival, and the build up of battleships too expensive. It is far fetched to claim the Anglo-German arms race as a significant cause of the war, but it did indicate Britain’s sense of insecurity and likely help to push her closer into the FrancoRussian entente (especially since the 1905 Russo-Japanese War had temporarily eliminated Russia as a naval rival in the Mediterranean). 20 By 1914, many of Europe’s military leaders were convinced that war was inevitable – a sense of pessimism prevailed. Given the existing tensions, all states had developed detailed war plans that relied on precise timing and railway schedules to gain the advantage of speedy mobilization (this is what won the Franco-Prussian War, 1870). Germany, maintaining a policy of trying to keep the largest army in Europe, was by 1914 struggling to keep pace with Russian build up and advantages in manpower. Germany’s high command were worried that within a few years Russia would have finished military upgrades, would be more industrialized and would have completed its railways into the western frontier – Germany would be doomed, according to Germany’s military strategists. 21 Geographically “encircled” by France and Russia, Germany feared being cut to pieces fighting a two-front war. The Schlieffen Plan was to remedy this situation by attacking and defeating France first, because Russia would take longer to mobilize, then putting troops on trains to meet the Russians. This had two important consequences: 1. Schlieffen required Germany to break the 1839 Treaty of London guaranteeing Belgium’s neutrality. France’s northern borders were undefended. 2. The plan necessitated Germany to involve France in a continental war in any conflict involving Russia, thus making a wider war more likely in a local conflict involving the Balkans. 22 Germany’s Schlieffen Plan was designed to outflank France’s army and capture Paris in a short number of weeks, but required an impossible rate of speed to move men and materials. Germany was not unique in having planned for war. All the Great Powers had similar plans, such as France’s Plan XVII which planned an attack to reclaim Alsace-Lorraine. LINK TO WAR PLANS 23 “Secret plans determined that any crisis not settled by sensible diplomacy would, in the circumstances prevailing in Europe in 1914, lead to a general war. Sensible diplomacy had settled crises before, notably during the powers’ quarrels over position in Africa and in the disquiet raised by the Balkan Wars of 1912-13. Such crises, however, had touched matters of national interest only, not matters of national honour or prestige…” -John Keegan, The First World War “During the final period before the outbreak of general war, one appalling fact becomes terrifyingly clear: the unrelenting rigidity of military schedules and timetables on all sides. All these had been worked out in minute detail years before, in case war should come.” – A. Stoessinger, Why Nations Go to War, p. 14) 24 Historians generally recognize that some long-term developments played a role in the outbreak of war in 1914: 1. Franco-Prussian War (1870-1914); “the German Question” 2. Collapse of Ottoman Empire & Balkan independence movements; “the Eastern Question” 3. Russo-Japanese War and 1905 Revolution 4. Austro-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia (1908) 5. Balkan Wars (1912-13) 25 Those who argue convincingly that Germany was most responsible for the conditions that created a general war point out a recklessness and aggression that was apparent long before 1914: 1. Moroccan Crises (1905, 1911) 2. Naval arms race and military build up 3. Seeking “a place in the sun” – empire building in Asia and Africa 4. Ambitions in the Middle East was a threat to Suez (i.e. BerlinBaghdad railway) 5. Provided Krupp artillery guns to Boers and Afrikaners in Boer War; Kaiser’s public support for Britain’s enemies in the war “..it must be granted that [Germany’s] policies had for some years been rather peremptory, arrogant, devious and obstinate.” - Palmer, Colton, Kramer, A History of the Modern World 26 Some historians point out that all European states faced potential home-grown problems by 1914, that made the gamble of war (“rolling the iron dice”) seem like a attractive solution: 1. Germany: Rise in political power of socialists in Reichstag; demands for greater democratization and powersharing was feared by traditional elites and industrialists. Successful war would unify the people behind the Reich 2. Austria-Hungary: Very multi-ethnic population. Successful war against Serbia and Russia would give them dominance in the Balkans and end nationalist disturbances. 27 3. Russia: Tsar had recovered from 1905 by allowing a Duma (parliament) but had been restricting its powers. Increasingly relied on middle class and working class for industrialization, but did not want to share power or reform government. In the last years before war, the Duma’s powers were curtailed and the intelligentsia was increasingly antagonistic against Tsardom. Russian Empire contained hundreds of minorities and were disunited. Attempts to “Russify” minorities had failed. Civil unrest and strikes had rocked Russia in the last years before the war. Successful war would unify the people behind the Tsar and avoid future revolution. 28 4. 5. France: Had been rocked by military scandals, strikes and labour unrest. Industrial growth and population growth were stagnant and faced a bleak future. Britain: Support for socialist Labour Party growing amidst declining economic growth. “Troubles” in Ireland – terrorism, violence, revolt, and threat of civil war Had suffered some shocks to its prestige and was losing ground to USA and Germany as the prime economic power. German exports were challenging British economy. 29 Overall, it seems very insufficient that internal reasons would explain why Europe’s leaders gambled on war. Without exception, every state’s population rallied to the call of war and supported it when it came. There was little danger of revolution anywhere except for Russia, and that circumstance was made worse after the war had begun. Ultimately, what ever was going on inside these states, it was the assassination of Franz Ferdinand in Bosnia, that lead their leaders on the path to war. 30 War was by no means inevitable, human actors still made decisions and miscalculations that led to war. Most of these occurred between June 28 and August 4, 1914, otherwise known as the “July Crisis”. Could you have avoided it? 31 “…the mere narration of successive crises does not explain why the chief nations of Europe within a few days became locked in combat over the murder of an imperial personage…” -Palmer, Colton, Kramer, The History of the Modern World “…There seems to be no obvious connection between the murder committed by a young man and the clash of armies of millions…” J.A.S. Grenville How did the assassination of Franz-Ferdinand create a global war? 32 1. June 28, Sarajevo, Bosnia – Franz Ferdinand and his wife assassinated Gavrillo Princip, a Serb nationalist, supported an encouraged by the Black Hand, a terrorist organization hoping to cause a war that would free Slavs from the Hapsburgs. Franz Ferdinand was a moderate reformer who might have found compromise and allowed nationalist autonomy within the empire. This would potentially have frustrated Serb goals. No direct link to official Serbian government involvement has ever been proven, but the government of Prime Minister Nikola Pasic and King Alexander were powerless against the military leadership – Serbia’s civilian government did not want war (having just fought in two Balkan Wars) 33 2. 3. 4. 5. Austria-Hungary could not let Serbia go unpunished and retain prestige as a “great power”. Meant to send a message to nationalists. Russia had backed down in previous Balkan crises and felt it could not back down in this one. Germany had mounting paranoia about the improvement of Russia’s armies, and the dependability of their weak ally – leaders feared war with Russia or France, not rising out of the AustroSerbian dispute, might not result in Austria-Hungary on Germany’s side? Germany seems to have gambled on one of two “ifs”: that France might not support Russia, and the Central Powers would win a diplomatic victory (and Germany could win back alliance with Russia); or, that if war was to come, then now is better than later. 34 6. July 23 – Vienna sends an ultimatum to Serbia. Serbia was to allow Austria-Hungary to investigate the assassination within Serbia’s borders. The Austrian diplomat who delivered the ultimatum made preparations to leave Belgrade as soon as possible, indicating that Vienna never expected the ultimatum to be accepted. 7. July 25 – Serbia carefully worded a reply that accepted all the demands except Austrian supervision, and then mobilized her army. 8. Kaiser Wilhelm II “was delighted” upon hearing acceptance of the Serbians and falsely assumed, briefly, that “every cause for war has vanished” – the Allied charge that he thirsted for war at this moment, is not supported by historical evidence. (Historian David Fromkin alleges that the Bethmann-Hollweg and the German high command kept true intentions from the kaiser) 35 9. July 28 – instigated by German Chancellor Bethman-Hollweg, and Austrian Chancellor Berchtold, Austria-Hungary declares war. 10. July 25-28 – British foreign minister, Sir Edward Grey, tried to mediate a solution. The German government rejected Britain’s interference. 11. July 29 – Austrian artillery bombards Belgrade. 12. July 30 - Bethman-Hollweg resists calls for mobilization and encourages Austria to localize the war through dialogue with Moscow. (This results in the “Willy-Nicky” telegrams.) Russia now under pressure by military leaders, and France (worried Russia is unprepared) to mobilize. France ensured Russia of support somewhere between July 20-23) 36 13. July 31 – Russia began full mobilization after having started “partial mobilization” on July 29; this however, was technically impossible. French military leaders (Joffre) demand France mobilizes. 14. By July 30, German high command (von Moltke) panicked that mobilization must begin and France must be defeated before Russia could complete mobilization. 15. August 1 – Germany declared war on Russia. Britain still refused to declare position to France. 16. August 3 – Germany declared war on France and invaded Belgium. 17. August 4 – Britain declared war on Germany, supposedly in defense of Belgian neutrality – “the slip of paper” 37 “What the coming of the war in 1914 reveals is how a loss of confidence and fears for the future can be as dangerous to peace as the naked spirit of aggression that was to be the cause of the Second World War a quarter of a century later. A handful of European leaders in 1914 conceived national relationships crudely in terms of a struggle for survival in competition for the world. For this millions would suffer and die.” - J.A.S. Grenville, A History of the World (2007) 38 The question of war guilt has been the focus of historical controversy ever since the Paris Peace Conferences in 1919. Our readings represent the two basic positions on the issue: 1. Palmer, Colton, Kramer, argue that the war was not Germany’s fault and therefore the verdict at Versailles in 1919 was flawed: “..it is not true that Germany started the war, as its enemies in 1914 popularly believed...” – Palmer, Colton, Kramer, A History of the Modern World, p. 687. 2. J.A.S. Grenville takes the traditional view that Germany and her allies were primarily responsible and therefore the verdict of Versailles was a justifiable one: “The responsibility for starting the conflict in July and August must rest primarily on the shoulders of Germany and Austria-Hungary…” - J.A.S. Grenville, A History of the World, p. 59. Which position is best supported by the evidence? 39 Key historians who argue that Germany was at fault: 1. A.J.P. Taylor, British historian 2. “war by timetable argument” – war plans, mobilization schedules, railroad itineraries put events beyond the control of the diplomats in the final days of the July Crisis however, the war plans were necessary because of Germany’s reversal in foreign policy after Bismarck’s retirement (1890) in which Germany became increasingly aggressive and allowed alliances to lapse, leading to encirclement David Fromkin (Europe’s Last Summer) argues that Germany deliberately used the assassination as a cause to start a global war The war was no accident. German military leadership were convinced that by 1916-18, Germany would be too weak to win a war with France, England and Russia – this was a war desired by Germany, especially von Molke. also argues that in all countries, but particularly Germany and Austria documents were widely destroyed and forged to distort the origins of the war. 40 Key historians who argue that Germany was at fault: 3. Fritz Fischer, German historian – the “Fischer controversy” is at the centre of the Great War origins debate link between domestic fears of the German power elite (capitalists & Junkers) and the expansionist aims of the Reich the Prussian elites wanted war since 1912 (the year of sweeping socialist gains in the Reichstag) and manipulated the Austrians into using the Casus Belli (lawful cause of war) created by the assassination of Archduke into starting WWI uses Bethmann-Hollweg’s plan (September Program, 1914) for annexations and economic mastery of Europe (Mitteleuropa) to argue that Germany planned the war to avoid democratization and gain hegemony over central Europe – is this “bad history”? continuity between the war aims of the Reich in 1914, and Hitler’s Nazis in the 1930s, and therefore there was something inherently rotten about Germany in the 20th century 41 Key historians who argue that “structural factors” are to blame: 1. Paul Kennedy, argues that Germany took the offensive against legitimate and real threats. 2. James Joll argues that interlocking system of alliances was responsible, but points to other pressures such as domestic problems. 3. George Kennan argues that the French-Russian alliance made war inevitable – any Balkan quarrel would erupt in war 4. Arthur Stoessinger argues that ultimately it was the system of decision making in all of the Great Power governments that caused the war – a handful of arrogant, stubborn and careless leaders dragged millions into war. 42 “Finally, one is struck with the overwhelming mediocrity of the people involved. The character of each of the leaders, diplomats, or generals was badly flawed by arrogance, stupidity, carelessness, or weakness. There was a pervasive tendency to place the preservation of one’s ego before the preservation of the peace.” - Stoessinger, Why Nations Go To War 43 Key historians who focus away from Germany: 1. Arno Mayer – equally distributes blame, but Austrians were especially desperate for war. advocates that all of Europe - not just Germany - was beset by domestic disturbances; all conservative European statesmen consciously used popular nationalism and edged closer to war to preserve their social systems from political opposition parties 2. Samuel Williamson argues that Austria’s role has been overlooked. The decision to wage war was ultimately Austria’s. 3. Barbara Tuchman argues that careless and belligerent Russian mobilization turned a local crisis into global war. 4. Niall Ferguson refutes the notion that militarism, imperialism, nationalism or the arms race made war inevitable – British policy in the decade before 1914, but especially British diplomacy under Sir Edward Grey created a global conflict from the local crisis. 44 “…Behind the ‘governments’ – the handful of men who made decisions in Berlin,Vienna, Paris and St. Petersburg – stood populations willing to fight for republic, king and emperor. Only a tiny minority dissented. For the largest socialist party in Europe, the German, the war was accepted as being fought against tsarist Russian aggression. The different nationalities of the Dual Monarchy [Austria-Hungary] all fought for the Hapsburgs, the French socialists fought as enthusiastically in the defence of their fatherland ruthlessly invaded by the Germans…” - J.A.S. Grenville, A History of the World 45 Explain why “the mere narration of successive crises does not explain why the chief nations of Europe within a few days became locked in combat over the murder of an imperial personage”. Why did a world war break out in 1914? In what ways, and with what results, was nationalism both a unifying and destructive force in the nineteenth and early twentieth century? To what extent was Germany responsible for starting a global war in 1914? “The lights are going out all over Europe. We shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.” – Sir Edward Grey, August 4, 1914 46